Sejong, South Korea

This five-year-old city, slated to be South Korea’s new administrative capital, has something in abundance that the rest of the country doesn’t—kids.

For three years in a row, women in newly constructed Sejong (paywall) have had more children, on average, than anywhere else in the country. That’s no small feat at a time when Korea is battling a “birth strike,” with both births and marriages shrinking to all-time lows.

For Koreans who have aspirations of a quiet family life with children, Sejong is a prototype of what a city free of the stresses and high costs associated with marriage and child-rearing could look like. A columnist at Korean daily newspaper Joongang Ilbo imagined in a recent piece a place where the cost of education for children was low and after-work obligations were almost non-existent, and concluded that “a version of this utopia” existed in Sejong.

“Especially when it comes to time with family, Sejong city is like paradise,” said a 39-year-old mother-of-one surnamed Ahn, who works at the economy ministry. “I have female colleagues who only started going to parent-teacher meetings or their kids’ graduation ceremonies for the first time once they moved to Sejong.”

Baby-boom town

Most people would be hard-pressed to see Sejong as a utopia in any sense of the word at first glance.

A less ambitious take on other capital cities built from scratch—such as Canberra or Brasilia—it consists of an eerily quiet and unattractive sprawl of government buildings, surrounded by the sorts of identical high-rise apartment blocks with manicured parks found across South Korean urban areas.

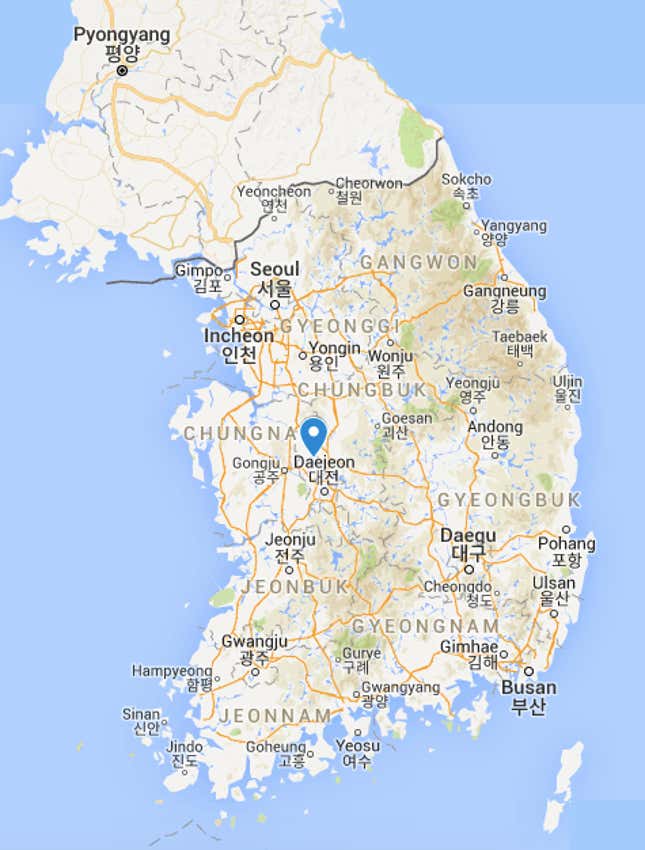

Since Sejong Special Autonomous City came into being in 2012 as part of a decade-old plan to shift official functions out of Seoul, some 75 miles away, more people have been relocating from the capital to Sejong. Its population tripled to over 300,000 by the latest count. The goal is to have 500,000 people living in Sejong by 2030, easing the burden in the Seoul area, where half the country resides.

On a recent stormy, weekday afternoon, the streets were mostly empty, but for a small perimeter in the city’s downtown area where pregnant women, mothers and grandmothers with children, and kids on bicycles and razor scooters crossed the streets, with no fear of traffic. Alongside the usual restaurants, coffee shops, and commercial buildings containing cram schools and other small businesses, a number of stores selling children’s clothing and toys were visible.

The high number of children in Sejong is no illusion. Last year, the city recorded a fertility rate of 1.67—a measure of the number of children a woman is expected to have in her lifetime—the highest level among 17 Korean provinces and cities. Meanwhile the national fertility rate hit an all-time low of 1.05—the lowest among OECD countries in 2015, the last year the organization made such data available. An average of 2.1 children is widely recognized as the rate needed for a population to remain stable.

Self-selection from couples about to start families moving to the city is likely a major factor. Lee Jae-kang, an official with the city’s policy planning bureau, said that many who decide to move to the city are newlyweds—the average age of the population there is 32.1 years old. The effect of local policies to encourage people to have children is also at play.

Many are drawn to the cheaper cost of living, green spaces, and a professional life where clocking off means going home to one’s family without the ritual of post-work drinking with colleagues that is indispensable to Korean work culture. Here, socializing is centered around family.

Another government worker, a 40-year-old mother of an eight-year-old boy, noted that when she goes out on weekends with her family, “It’s like everyone is a couple around my age with kids around my son’s age. It feels a bit unnatural, somehow.”

Happy mom

The crowning glory of Sejong’s policies, however, is its proud focus on the well-being of new moms.

Ju Myung-hee, a 35-year-old mother of three, was looking after her eight-month-old baby and attending a baby massage class at the city’s main government-run facility for new mothers, called Happy Mom Center. She relocated to Sejong from a neighboring city a year ago after her husband got a job there as a policeman. Life was a “bit lonely” at the beginning in Sejong, but she says she’s now made good friends through the center.

Lee, the Sejong government official, said that the Happy Mom Center was the first of its kind in Korea. Opened in October, it provides a range of mental and physical support services for pre- and post-natal needs, and offers services for fathers too, such as cooking classes. “When we planned this city we expected an influx of young families, with the possibility of a high birth rate, so we established this facility to care for their needs,” he said.

Since 2016, Sejong’s government started offering other maternity care services (link in Korean), such as assigning a caregiver to support new moms for 10 days after birth at a heavily subsidized rate, which includes childcare assistance and food preparation. The city also provides classes on lactation and childcare. In addition to the central Happy Mom facility, each apartment complex also has its own daycare center.

There’s another major incentive for people to have children—cash. Sejong city awards 1.2 million won ($1,110) for every couple for each child they have, a substantially more generous allowance compared to other local governments in Korea even as more are increasing (link in Korean) cash awards to get more people to have even a first child. Jongno district in Seoul, for example, gives 200,000 won for the first child—a new policy to be implemented in July—and 1 million won and 2 million won for the second and third child, respectively.

Still, Sejong isn’t to everyone’s taste. A working mother-of-two in Seoul surnamed Bae, whose husband works at the finance ministry, said her family rejected an offer to move there despite Sejong’s reputation as a child-friendly city. The 42-year-old expressed concerns about the quality of schools and after-school tutoring centers in Sejong compared to Seoul. Another option the family considered was to have the father commute to and from Seoul and Sejong while she stayed in Seoul with the child—a common arrangement for Korean families—but that would’ve been hard since she works too. Like Bae, other government workers have also cited not wanting to be split apart from their families as a reason not to relocate to Sejong.

But Sejong’s reputation for liveability, said Lee, the government official, is growing among even Koreans who don’t work in government jobs. Lee So-jeong, another mother of three who was attending a flower-tea-making class at the Happy Mom Center with her baby, moved to Sejong from a nearby city. Neither she nor her husband are public-sector workers.

“Where I used to live, when I stepped out of my apartment block it was just a parking lot,” said the 33-year-old, lauding Sejong’s relative greenness. In her new life, packed with activities with other new moms and her family, she said “there’s no time to be bored.”