Today, NASA unveiled the salty plumes of Jupiter’s moon Europa, but Texas Representative John Culberson beat them to it last week.

The lawmaker was in the middle of expounding on an annual preoccupation: Putting more money into a robotic space-exploration project expected to cost $8 billion or more by the time it launches sometime after 2022. The mission, called the Europa Clipper, aims to closely observe Europa, a distant moon of Jupiter, and could answer lingering questions about whether life exists elsewhere in the solar system.

“It’s worth noting that the scientific journal Nature Astronomy just reported that the Galileo mission, back in 1997, flew through a water plume on Europa a thousand kilometers thick,” Culberson explained while lawmakers doled out funding to NASA on May 9. “The ocean of Europa is venting into outer space.”

That news—confirmed observation of a plume of salt water, which suggests Europa’s environment could allow microbial life to develop—is a major reason why he is so eager for NASA to return. It was also embargoed until today (May 14) by Nature Astronomy.

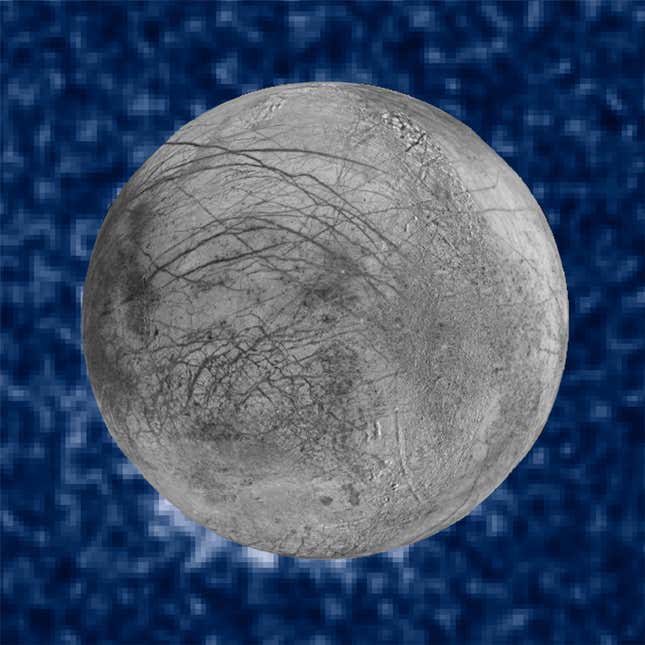

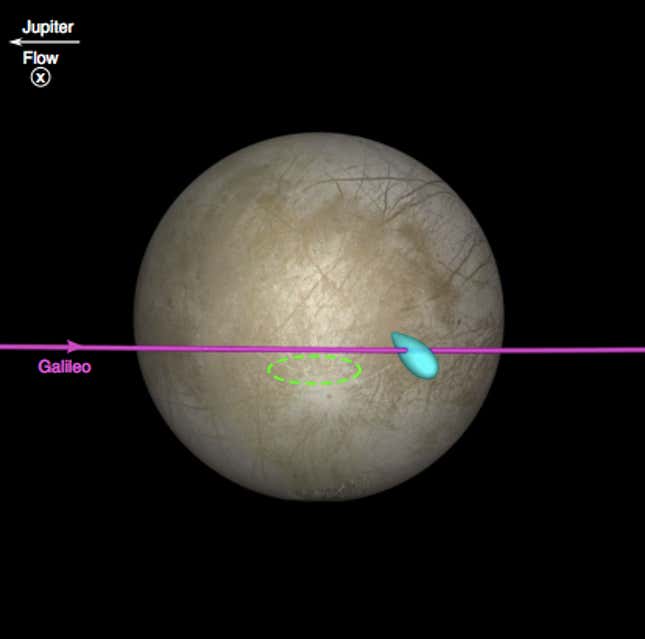

Officially, the researchers—Xianzhe Jia , Margaret Kivelson, Krishan Khurana, and William Kurth—report that instruments onboard the Galileo space probe detected intense, localized changes in the magnetic fields and plasma density of Europa’s atmosphere as the probe flew 400 km above the surface of the moon. These changes, the scientists believe, are consistent with images of the moon taken by the Hubble space telescope thought to show water ejecting from Europa’s surface.

When the three minutes of data associated with the plume were analyzed after the flyby in 1997, scientists thought it was a phenomenon of Jupiter’s magnetic fields. Other researchers revisited the data as they planned for future NASA missions to revisit the planet, creating a computer simulation of the conditions when Europa might eject water into its atmosphere. They found their simulation matched closely with the data from Galileo, giving them confidence to confirm that these magnetic signatures were caused by water escaping Europa’s ice shell.

Scientists have long believed Europa to be covered in a thick layer of ice. This new analysis adds backing to theories that an ocean of liquid salt water exists below the ice. Such a sea could provide shelter to bacterial life akin to that found in the depths of Earth’s oceans.

The Europa Clipper mission backed by Culberson would do as many as 45 close fly-bys, with new, more powerful instruments to “sniff and taste the stuff in the plume…and get a detailed composition of Europa’s interior,” as one of the researchers on the recent study put it at a NASA event.

“We know that Europa has a lot of the ingredients necessary for life as we know it. There’s liquid water, there’s energy, there’s some amount of carbon material, but the habitability of Europa is one of the big questions that we want to understand,” says Elizabeth Turtle, a Johns Hopkins planetary scientist who is developing the imaging system for the Europa Clipper. ”There may be ways for material from that ocean to come out above that ice shell, and that means we’d be able to sample it.

The Trump administration has frowned at the expense of this mission, but Culberson—not the only powerful lawmaker with an interest in extra-terrestrial life—has proven a wily defender of its funding. He has made common cause with supporters of the Boeing-built Space Launch System, a huge rocket NASA is developing to explore the solar system.

While many worry the SLS is too expensive to prove practical, it is arguably the only vehicle that could take the six-metric ton Clipper on a 600 km direct route to Europa. That could give the SLS one major advantage over SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, which looks to compete in lofting complex science missions for around one-fifth the cost of NASA’s rocket.