Every year, scientists discover about 18,000 species previously unknown to humanity—a delightful array of strange creatures with bizarre survival tactics.

Since 2008, the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York has been compiling a list of the top 10 new species, as determined by an international committee of taxonomists. The list is released annually on May 23, the birthday of Carolus Linnaeus, an 18th-century Swedish botanist considered the father of modern taxonomy.

This year’s compilation includes the tiny and tall, from deep-sea ocean dwellers to hitchhiking beetles and volcanic bacteria. The new species hail from Brazil, Costa Rica, Indonesia, the Canary Islands, Japan, Australia, China, and the US. Here’s the list, in order of minuscule to massive.

Anacorysta twista:

The enigmatic protist

Found on a brain coral in a tropical aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California, this single-celled protist is one mean mystery. It appears to have no near relatives and doesn’t fit neatly in any known group, though it may be a previously unknown early lineage of Eukaryota, a kind of organism—both single- and multi-celled—with genetic material packed in a membrane-bound nucleus.

Ancoracysta twista is a predatory flagellate, which is about as cruel as it sounds. The organism uses a whip-like flagella to propel itself while harpooning its prey—other protists. Baffled taxonomists think the unusually large number of genes in this creature’s mitochondrial genome shed some light on the early evolution of eukaryotic organisms.

Thiolava veneris: An explosive bacteria

Tagoro, a submarine volcano, erupted off the coast the Canary Islands in 2011, wiping out most of the marine ecosystem. The area has since been colonized by a new species of proteobacteria with filaments that cling to each other and form a massive white mat, extending for nearly half an acre at depths of about 430 feet.

The new species seems to have unique metabolic characteristics that allow them to survive in this newly formed underwater lava seabed. The proteobacteria are paving the way for new ecosystems to develop. Scientists call the filamentous mat of bacteria “Venus’ hair.”

Xuedytes bellus:

An adaptable b

eetle

Troglobitic beetles adapt to life in the permanent darkness of caves by losing their beetle shape and wings and growing long legs and bodies, taking on spider and ant traits. They are an example of convergent evolution, when unrelated species evolve similar attributes under pressure from the same selection forces.

This new species of troglobitic ground beetle from China is less than half an inch long, with a dramatically elongated head and body. It was discovered in a cave in Du’an, Guangxi Province, an area with many caves and a wide array of beetle species.

Nymphister kronaueri:

The beetle’s guide to hitchhiking

This miniature 1.5-millimeter beetle from Costa Rica is a myrmecophile, or ant-lover. It lives and travels with a single species of nomadic army ants, called Eciton mexicanum. The host ants spend two to three weeks on the move, followed by two to three weeks stationary, and the the beetle goes with them from place to place.

Its body is the same size, shape, and color of the abdomen of a worker ant. The beetle uses its mouth to grab the skinny portion of the host abdomen, hitching a ride as the ants amble. The beetles seem to use chemical signals or other adaptations to avoid becoming ant prey themselves, but how that works in this case is as yet unknown.

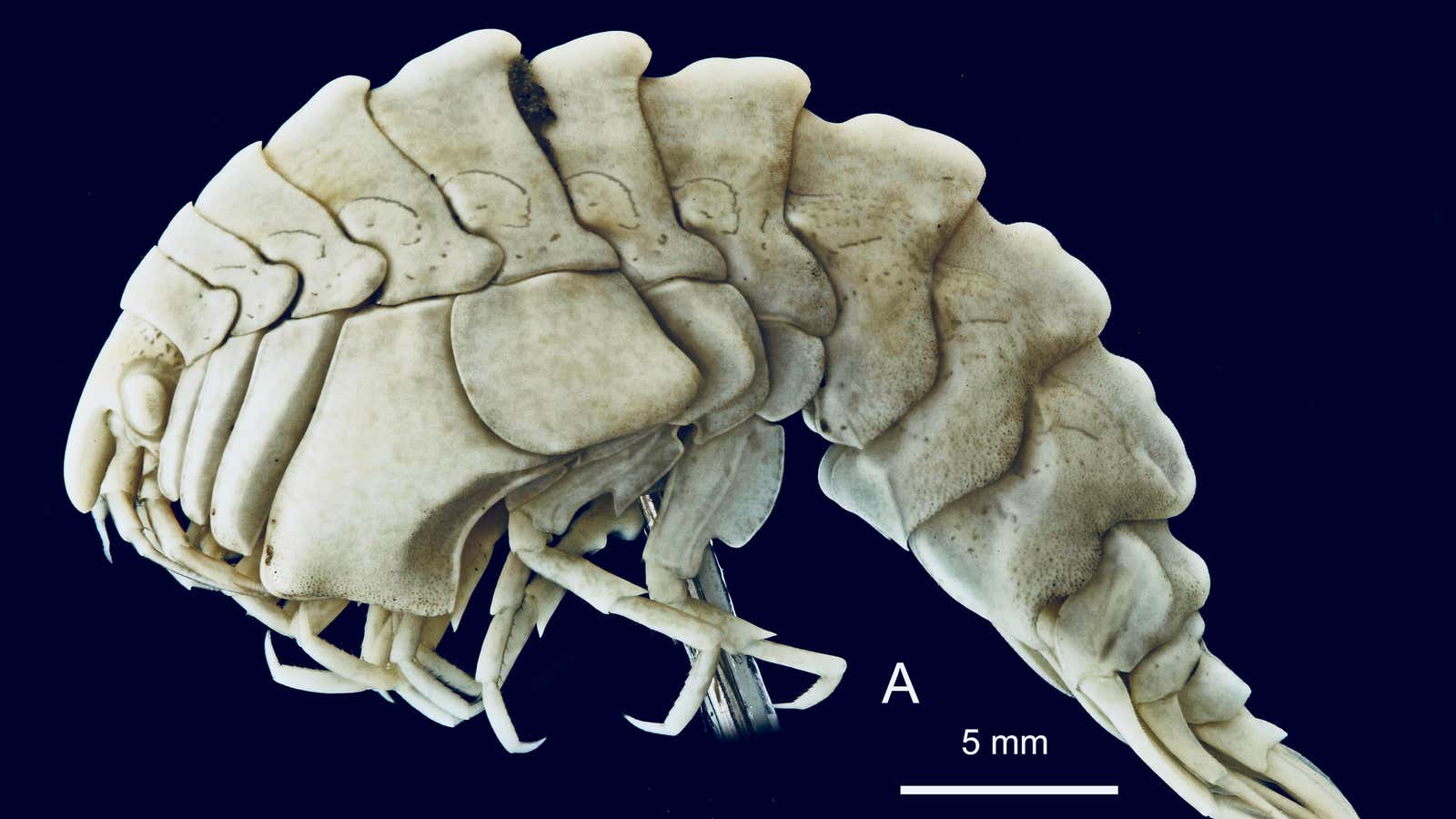

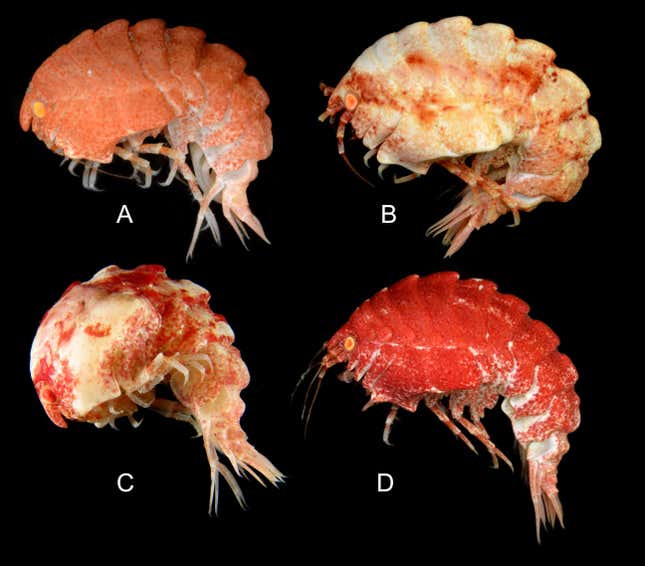

Epimeria Quasimodo:

A literary amphipod

This 2-inch Antarctic Ocean amphipod with a humped back is named for Victor Hugo’s character, Quasimodo, in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. It’s one of 26 new species of amphipods of the genus Epimeria from the Southern Ocean, known for their incredible spines and vivid colors. Taxonomists say they look like tiny versions of mythical dragons.

The genus is abundant, which has led some scientists to argue that it must have been known. But that’s not so, according to the ESF statement.

“Using a combination of morphology and DNA evidence … investigators have demonstrated in [a] comprehensive monograph just how little we yet know of these spectacular invertebrates,” the taxonomists write.

Pseudoliparis swirei:

The deepest fish

In the dark abyss of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, about 27,000 feet down, lives the deepest fish ever discovered. The Mariana snailfish is a tadpole-like 2- to 4-inch creature that’s much more successful than it looks; this small, translucent fish appears to be the top predator of her underworld.

Human divers cannot go where Mariana snailfish swim, but an international research team did sink cameras and traps deep into this difficult-to-reach and rarely-studied area over three years. The traps took four hours to fall from the ocean’s surface to where this snailfish swims. When raised, they held healthy, well-fed snailfish, and the camera footage had captured their deep sea activities. Scientists believe that 27,000 feet is a physiological limit for fish, and that below this depth, none can survive.

Sciaphila sugimotoi:

Plant prankster

This 4-inch Japanese plant is a friendly mooch. Unlike most plants, which capture solar energy to feed through photosynthesis, this one lives off of other organisms. Specifically, it nourishes itself from a fungus, to which it doesn’t do any harm.

This plant appears in only two locations on Ishigaki Island in September and October, producing small blossoms. Due to its rarity, this new plant species is already considered critically endangered, as it depends on very stable ecosystems and only flourishes in humid evergreen broadleaf forest.

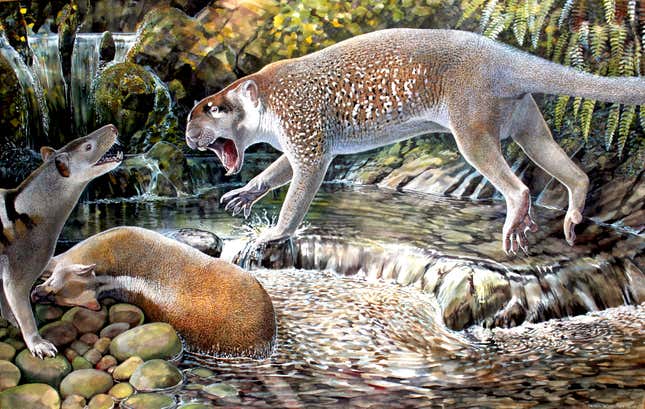

Wakaleo schouteni:

Tree-climbing lion

New research on fossil findings in Australia lead scientists to believe that in the late Oligocene era, about 23 million years ago, a tree-climbing marsupial lion roamed the open forest in Queensland. They believe the lion was about 50 pounds, “more or less the size of a Siberian husky dog.”

Based on its teeth, the lion was likely an omnivore, eating meat and vegetation alike. It is part of a lineage, the genus Wakaleo, that grew over time, possibly in response to larger prey that evolved as the flora changed and the continent became drier and cooler.

Pongo tapanuliensis: An ape unlike others

An isolated population of great apes in southern Sumatra in Indonesia appears to be a distinct species of orangutan, unlike any other. Genetic evidence suggests that this southern species diverged from other, like great apes about 3.38 million years ago.

The finding that this type is unique also makes it the most imperiled great ape in the world. Only an estimated 800 such creatures live in a habitat spread over about 250,000 acres. They are about the same size as other orangutans, with females under 4 feet tall and males under 5 feet tall.

Dinizia jueirana-facao:

A tree grows in Brazil

This 130-foot 62-ton Brazilian tree stands majestically above the canopy of the Atlantic forest, growing woody fruit about 18 inches long.

It exists only within the boundaries of the Reserva Natural Vale in northern Espirito Santo. There are only about 25 such trees living, making it critically endangered. The Atlantic forest is home to more than half of the threatened animal species in Brazil.

All these classifications are a lot of fun to read about—but they’re also urgent business, according to ESF president Quentin Wheeler. Because of climate change and human impact on environmental habitats, species extinctions outpace discoveries. ”We name about 18,000 per year but we think at least 20,000 per year are going extinct,” he says. “Many of these species—if we don’t find them, name them and describe them now—will be lost forever.”