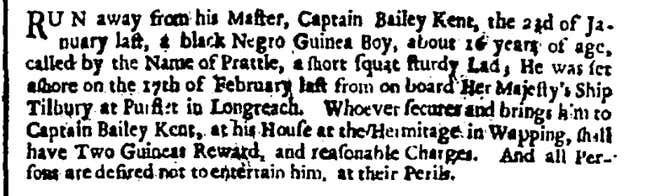

Nestled among ads for new books, medicines, and clothes was a startling request for help. “Run away from his master, captain Bailey Kent, the 23rd of January last, a black negro Guinea boy, about 16 years of age, called by the name of Prattle, a short squat sturdy lad,” the newspaper notice reads. “Whoever secures and brings him to captain Bailey Kent, at his house at the Hermitage in Wapping, shall have two guineas reward, and reasonable charges.” The advertisement, placed in the London Gazette in 1705, warns readers against helping the boy. Those tempted do so “at their peril.”

In the UK, the transatlantic slave trade is often taught as something that took place primarily in the Caribbean, the Americas, and South Asia, says Simon Newman, a professor of American history at the University of Glasgow. But the advertisement points to an uncomfortable truth: there were plenty of enslaved people in mainland Britain, too.

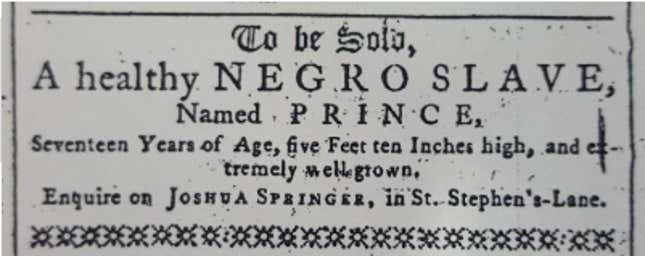

In fact, Newman and his team of researchers found over 800 runaway slave ads published in English and Scottish newspapers between 1700 and 1780. They also found almost 80 ads selling slaves. The material highlights the normality of the practice; people felt comfortable enough to advertise runaway slaves or publicly offer a slave for sale in papers read by their by friends and neighbors.

The research, which took three years to complete, was painstaking work. While researchers were able to digitally search some newspapers for runaway slave adverts, it wasn’t always possible. Often, researchers had to go through tens of thousands issues of 18th-century newspapers by hand.

They placed the collected ads into a public database. Newman believes these notices are just “the tip of the iceberg,” since few enslaved people ever ran away and not all masters placed ads calling for help finding those who did. Thus, the database likely represents a small proportion of the total number of slaves who lived in Britain in the 18th century.

The database includes both full transcriptions and, when possible, reproductions of the advertisements. They were placed all over the UK; from Scotland, to Liverpool, to Bristol.

The slaves in the ads were largely of African descent, but a few were Indian or Native American. The ads also described their clothing, hairstyles, skills, and mannerisms. They indicate that many of the enslaved in mainland Britain worked as servants in the houses of wealthy masters and mistresses. The database suggests enslaved people in Britain were better housed, clothed, and fed than those in British colonies. That said, it was still an incredibly traumatic experience to be taken from their family and community and forced to serve another.

The threat of being returned to the colonies also loomed large. In one runaway ad, the master of Jamie Montgomery, an enslaved man who had been in Scotland for five years, during which time he had become a skilled carpenter and joined a church, was determined to send the young man back to the American colonies for sale. Montgomery attempted to escape, but ultimately failed. In another “for sale” ad, a master indicates that if the unnamed nine-year-old boy was not purchased, he would return him to the West Indies.

“300 years ago, Britain was a multiracial, multicultural society. We’ve forgotten that and it’s worth remembering,” Newman says. He adds that though the adverts reveal another aspect of the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, it also shows that a lot of people could escape their masters and create a life for themselves in Britain.

There’s evidence some enslaved people went on to join churches, were baptized, and assimilated into local areas. Some were even able to marry into the white community. While interracial marriages were illegal in the colonies, they weren’t in mainland Britain. Newman suggests this was because the black and South Asian population was such a tiny minority that they were not perceived as threatening to the white population.

Newman plans to create teaching materials, such as a graphic novel, from the insights gleaned from the database. It provides an opportunity for both white and ethnic minority students to engage with the darkest chapters of British history. While the practice of slavery is difficult to stomach, Newman was encouraged by the response from classes he led in East London, especially among ethnic minority students. “Learning about Tudor kings is one thing, but then realizing in that same society, there were people who looked like you was very important to those students,” he says.

The database is just the beginning. Newman hopes people use it to conduct further research on the history of slaves and piece together the lives these individuals led.