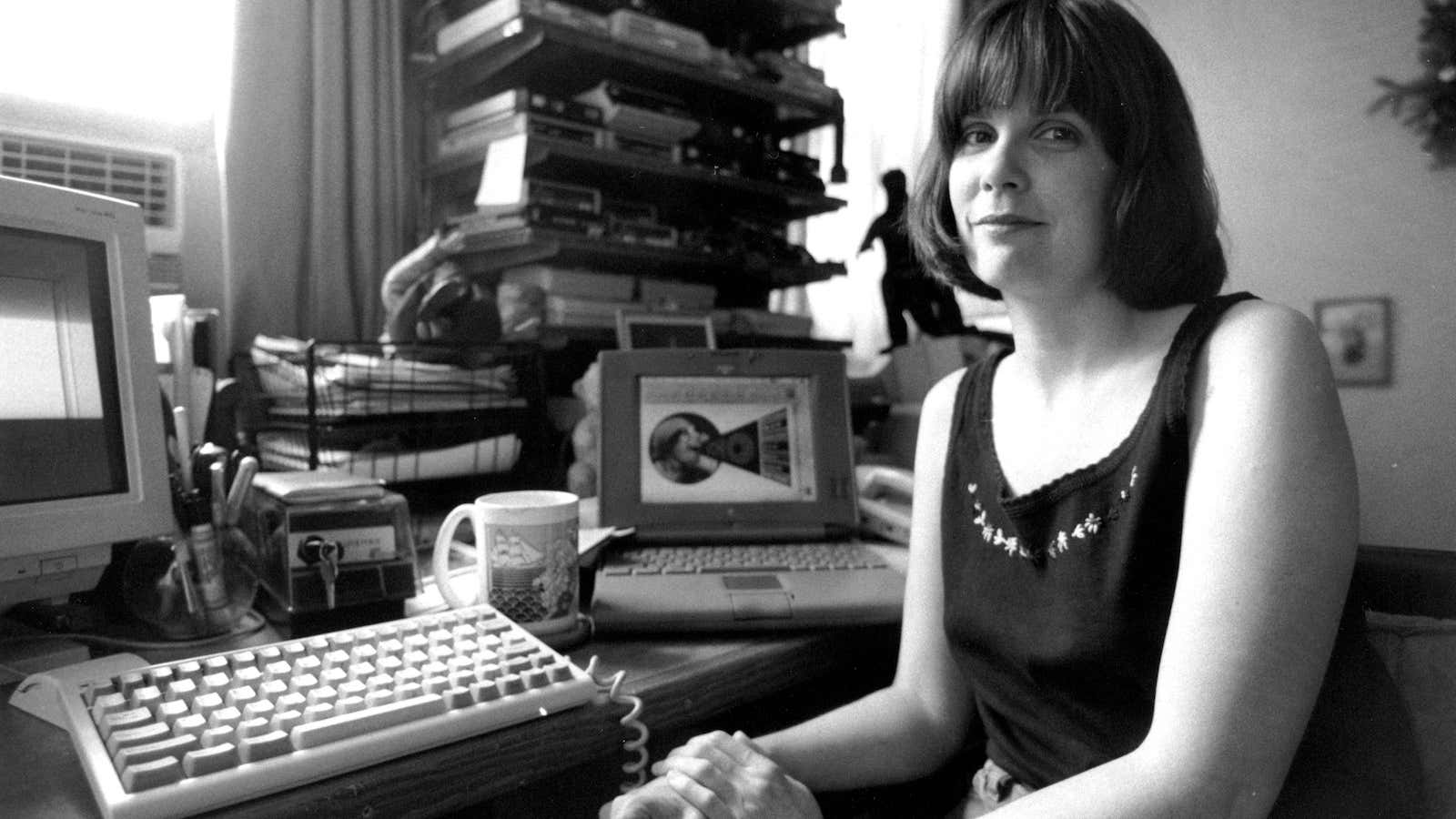

In 1989, a graduate student named Stacy Horn started an online community. This was before the World Wide Web, when “online” still meant a Bulletin Board System, or BBS, a text window you dialed on the phone and paid for by the hour. Such communities once numbered in the tens of thousands, managed by system operators with a scope of regional and subcultural interests as diverse as anything online today: computer hobbyist culture, dating, politics, and, of course, Star Trek. Since Stacy lived in New York, she named her BBS Echo—the “East Coast Hang-Out.”

Founded before the first web browser, Echo still exists today, nurturing a small but devoted family of users. This makes it among the oldest continuously operating online communities in history. It has achieved this status by keeping its head down: Although she received offers, Stacy never sold, franchised, or sold ads. She never indulged the fantasy of a lucrative, bubble-era IPO. She never even made the jump to the web, leaving Echo outside of time: It remains Unix-based, a text-only world accessible only to those who have sent away for login information that Stacy issues, along with a welcome letter, by post.

Stacy Horn’s story is an antidote to contemporary digital life. Silicon Valley’s myth-makers have rarely paid attention to scrappy community-builders like her. Rather, they’ve sold us on serial entrepreneurship—on founders whose financial successes justify our cultural obsession with so-called “unicorn” startups, often with no clear pathway to sustainability beyond aggregating users and clout.

Echo represents a lost vision of social media. If Facebook, Instagram and Twitter are big social, then Echo is small social. It’s also just what we need right now.

* * *

Back when women only made up a tenth of the online population, Echo’s user base was 40% female. On its website, a banner read: “Echo has the highest population of women in cyberspace. And none of them will give you the time of day.” Stacy made Echo membership free for women for an entire year. She created private spaces on Echo where women could talk amongst themselves and report instances of harassment. She spoke to women’s groups about the internet, and she taught Unix courses out of her apartment so that a lack of technical knowledge would not limit new users to the experience of computer-mediated communication.

In short, Stacy achieved near gender parity on an almost entirely male-dominated internet because she cared enough to make it so.

For many in tech, caring means caring about: investing, without immediate promise of remuneration, in the pursuit of building something “insanely great,” as Steve Jobs once said. It means risking stability and sanity in order to change the world.

But what Stacy’s legacy represents is caring of another sort: not only caring about but caring for. It is this second type of caring that has been lost in our age of big social.

Moderators are a key part of this relationship. Stacy was a founder-moderator: a combination of tech support and sheriff who thought deeply about decisions affecting the lives of her users. She baked these values into the community: Every conversation on Echo was moderated by both a male and a female “host,” who were users who, in exchange for waived subscription fees, set the tone of discussion and watched for abuse.

In The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, an early book about online community, Howard Rheingold documents such hosts all over the early internet, from a French BBS whose paid “animateurs” were culled from its most active users to the hosts on Echo’s West Coast counterpart, The WELL. “Hosts are the people,” he wrote, who “welcome newcomers, introduce people to one another, clean up after the guests, provoke discussion, and break up fights if necessary.” Like any party host, it was their own home they safeguarded.

Today the role of moderators has changed. Rather than deputized members of our own community, they are a precarious workforce on the front lines of digital trauma. The raw feed of flagged Facebook content is unimaginable to the average user: a parade of violence, pornography, and hate speech. According to a recent Bloomberg article, YouTube moderators are encouraged to work only a few hours at a time, and have access to on-call psychiatry. Contract workers in India and the Philippines work far removed from the content they moderate, struggling to apply global guidelines to a multiplicity of cultural contexts.

No matter where you’re located, it’s not easy to be a moderator. The details of such practices are “routinely hidden from public view, siloed within companies and treated as trade secrets,” as Catherine Buni and Soraya Chemaly note in a 2016 study of moderation for The Verge. They’re one of Silicon Valley’s many hidden workforces: Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter thrive on the invisibility of such labor, which makes users feel safe enough to continue engaging—and sharing personal data—with the platform. To sell happy places online, we are outsourcing the unhappiness to other people.

How did we stop caring about the communities we created? This is partially a question of scale. With mass adoption comes the mass visibility of brutality, and the offshore workers and low-wage contract laborers who moderate the major social media platforms cycle out quickly, traumatized by visions of beheadings and sexual violence. But it’s also a design choice, engineered to make us care about social platforms by concealing from us those who care after them. Put simply, we have fractured care.

The major platforms’ solution to the problem of scale has been to employ contract workers to enforce moderation guidelines. But what if we took the opposite approach and treated scale itself as the issue? This raises new questions: What is the largest number of people a platform can adequately care for? Can that number really be in the billions? What is the ideal size for a community?

Perhaps big social was never the right outcome for this wild experiment we call the internet. Perhaps we’d be happier with constellations of smaller, regional, and interest-specific communities; communities whose stakeholders are the users themselves, and whose moderators and decision-makers aren’t rendered opaque through distance and centralized authority. Perhaps social life doesn’t scale. Perhaps the future looks very much like the past. More like Echo.

Instead of expanding forever outward, we could instead empower groups of people with the tools to build their own communities. We have a long history of regional Community Networks and FreeNets to learn from. A generation of young programmers and designers are already proposing alternatives to the most baked-in protocols and conventions of the web: the Beaker Browser, a model for a new decentralized, peer-to-peer web, built on a protocol called Dat, or the zero-noise, all-signal community of Are.na, a collaborative social platform for thinkers and creatives. Failing those, a home-brew world of BBS—Echo included—exists still, for those ready to brave millennial-proof windows of pure text.

* * *

There is nothing inevitable about the future of social media—or, indeed, the web itself. Like any human project, it’s only the culmination of choices, some made decades ago. The internet was built as a resource-sharing network for computer scientists; the web, as a way for nuclear physicists to compare notes. That either have evolved beyond these applications is entirely due to the creative adaptations of users. Being entrenched in the medium, they have always had a knack for developing social commons out of even the most opaque screen-based places.

The utopian idealism of the first generation online influenced a popular conception of the internet as a community technology. Our beleaguered social media platforms have grafted themselves onto this assumption, blinding us to their true natures: They are consumption engines, hybridizing community and commerce by selling communities to advertisers (and aspiring political regimes).

It would serve us to consider alternatives to such a limited vision of community life online. For original tech pioneers such as Stacy, success was never about a successful exit, but rather the sustained, long-term guardianship of a community of users. Now more than ever, they should be regarded as the greatest resource in the world.

This article is part of Quartz Ideas, our home for bold arguments and big thinkers.