Most trading days are pretty uneventful in the grand scheme of things. But when documenting the uneventful, what a difference 180 years makes.

The US Library of Congress’s Chronicling America site makes it relatively easy to sift through the news of the day way back when, and try to picture yourself making sense of the markets at the time. You quickly learn that tariffs, technology, and trade were as prominent then as they are today (paywall).

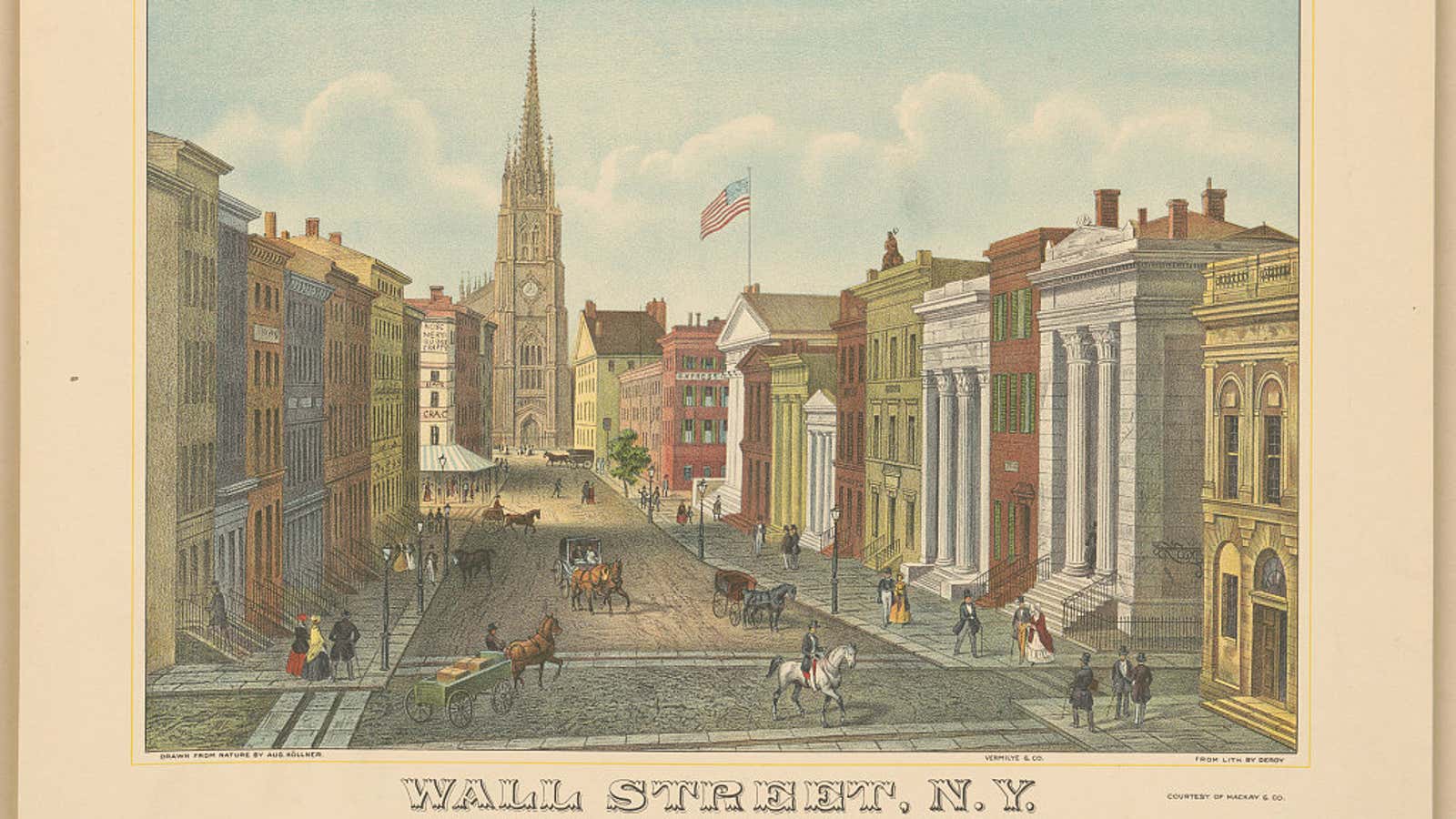

But these missives from the past are barely recognizable as vital, market-moving information, and more revealing of what life was like as an investor: You check your brokerage account, read the news, maybe shuffle things around a bit, and then take your horse and buggy home and forget all about it, until you repeat the cycle the next day.

The routine roundups of unremarkable trading days can be especially revealing. These days, a note tucked deep in the financial pages may say something like, “Stocks were little changed on Monday, as institutional investors largely stayed on the sidelines. Fears of high valuations have made traders cautious, with low liquidity stoking occasional bouts of volatility amid signs that a correction is likely in the coming months.” A market strategist could then be quoted saying something like, “At lower support levels we expect volumes to return, as investors take advantage of more reasonable multiples.”

In the market report for June 25, 1838, an anonymous reporter for New York’s Morning Herald wrote much the same, albeit in five delightfully meandering run-on sentences that suggested he had something—a sagging portfolio? A long-term grudge? Angst at filling column inches on a slow news day?— to get off his chest:

Wall street presents the same appearance of inactivity, nor do we anticipate any change until some definite movement takes place with regard to the hobby of the administration but go as it will, we imagine there must yet be a great fall in prices generally before the financial affairs of the country can become firm. The prices at which stocks and other securities are held, are without doubt fictitious values, that is, they hold the inflated rates, nearly, to which they were carried under the influence of the rage for speculation and stock gambling which prevailed two years since, when immense fortunes were realized on humbug lots, delightfully situated on Cape Flyaway, that magnificent watering place for day dreaming speculators. The nominal value which was then affixed to every kind of property still attaches to the stock market, hence the sensitiveness of the dealers, which causes prices to rise or fall 5 or 6 per cent with every breath or trifling rumor which is circulated by the designing. So soon as the fall business starts, which will now be soon, there will be a greater demand for money than exists at present, and the mass of the capital now afloat will be absorbed in in the natural course of business, without leaving any surplus for the maintenance of the disposition to speculate which still lingers in Wall street, and sends up prices to extravagant rates with every favorable rumor which is made public, therefore we are of opinion that a few months of renewed business will have the effect to bring down the rates of securities to their real values, at which there will be business enough done to satisfy the reasonable. The markets will then be firm, and not subject to the sudden fluctuations incident on the false position which they at present occupy.

What happened to our faithful correspondent the next day, the next week, the next year? Was he okay? Did he find peace?

On this day in 1838, stocks were little changed.