People in Shanghai don’t want to be told how they should address their grandmothers.

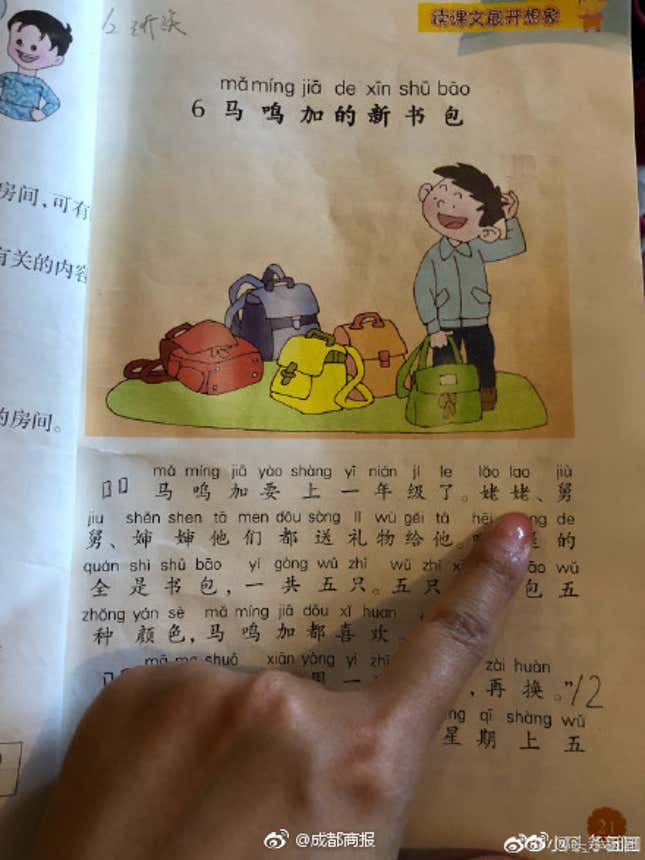

China’s internet erupted into debate over what the proper word for “grandmother” in Chinese is, after photos began circulating (link in Chinese) on social network Weibo last week showing that some Shanghai elementary school textbooks had started using the word lao lao (lăo lao) for “grandmother,” instead of wai po (wài pó), which is more common in Shanghai. Local education authorities said that wai po was a dialect term, while lao lao was the standard Mandarin word, according to a screenshot of a response from the education commission to an inquiry about the change that was issued last year, though the incident didn’t gain attention until recently.

The controversy is more than a matter of “nan” vs. “granny”—it’s one that strikes at long-running tensions between the central government and China’s provinces when it comes to language, as many worry that attempts to standardize Chinese will further erode the use and influence of local dialects.

Both lao lao and wai po (links in Chinese) refer to one’s maternal grandmother, according to the Xinhua online dictionary, which people use to look up words in China. Qian Nairong, a language expert at Shanghai University, said that (video, link in Chinese) lao lao was a Beijing dialect word that was later absorbed into standard Mandarin, but that wai po is very widely used in Mandarin. Other internet users noted that (link in Chinese) lao lao is a word commonly used in the north of China, but not in the south, which encompasses Shanghai.

Shanghai education authorities apologized (link in Chinese) on Sunday (June 24) and said they would change lao lao back to wai po in the following editions of the textbooks our of respect for the author’s word choices.

The growing dominance of standard Chinese in the last two decades, or Putonghua, which means “common language,” is a particularly touchy issue in Shanghai. Shanghainese is part of the Wu family of Chinese languages, known for containing notoriously difficult dialects (paywall). The Wu languages are spoken by about 70 million people, primarily in coastal Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. Like many of these, Shanghainese is a language under threat, said David Moser, a linguist and author of A Billion Voices: China’s Search for a Common Language, with some 40% of citizens (link in Chinese) in Shanghai aged below 25 only speaking Mandarin at home and not Shanghainese.

Since 2000, when the Chinese government enacted a law to make Mandarin the sole national language, dialects have become an increasingly contentious, and emotionally charged, issue. Beijing doesn’t officially ban minority languages, but often authorities give Mandarin greater priority over minority languages in schools and other areas of life. Around 73% of the country’s population (link in Chinese) can speak Mandarin as of 2017, according to China’s education ministry. Those who belong to ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans, don’t use Mandarin as their primary language. Beijing wants 80% of the population to speak Mandarin by 2020.

Nowhere has the linguistic tension been more manifest than in southern Guangdong province, where people have repeatedly challenged attempts by the central government to use Mandarin instead of Cantonese, for example on television. In mainland China, Cantonese is spoken by some 60 million in the south, while in Hong Kong the language is spoken by the majority of its 7.3 million inhabitants. Among the Han Chinese, which make up around 90% of the country’s population, some 1,500 dialects (paywall) are spoken.

Moser said that in the case of the word for “grandmother” in Shanghai, the Chinese government was “probably too strict and unreasonable.” In any case, any attempt to change the way that people call their grandmothers isn’t likely to succeed, as certain types of words such as ways of addressing family members are very resistant to change, he added. ”So if someone has been calling their grandmother by the name wai po since they were a child, they will certainly feel uncomfortable switching to lao lao, even though they now speak standard Putonghua rather than the southern dialect.”