The US Supreme Court today (June 26) decided Trump v. Hawaii (pdf), finding that Donald Trump’s “travel ban” on citizens from six predominantly Muslim nations and Venezuela has a “rational basis” in “legitimate state interests.” The justices were split 5-4, and a dissent by Sonia Sotomayor—in which she was joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg—argues that the majority ignored a “harrowing picture” of Trump’s animus against Muslims to reach its conclusion. Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan penned a separate dissent.

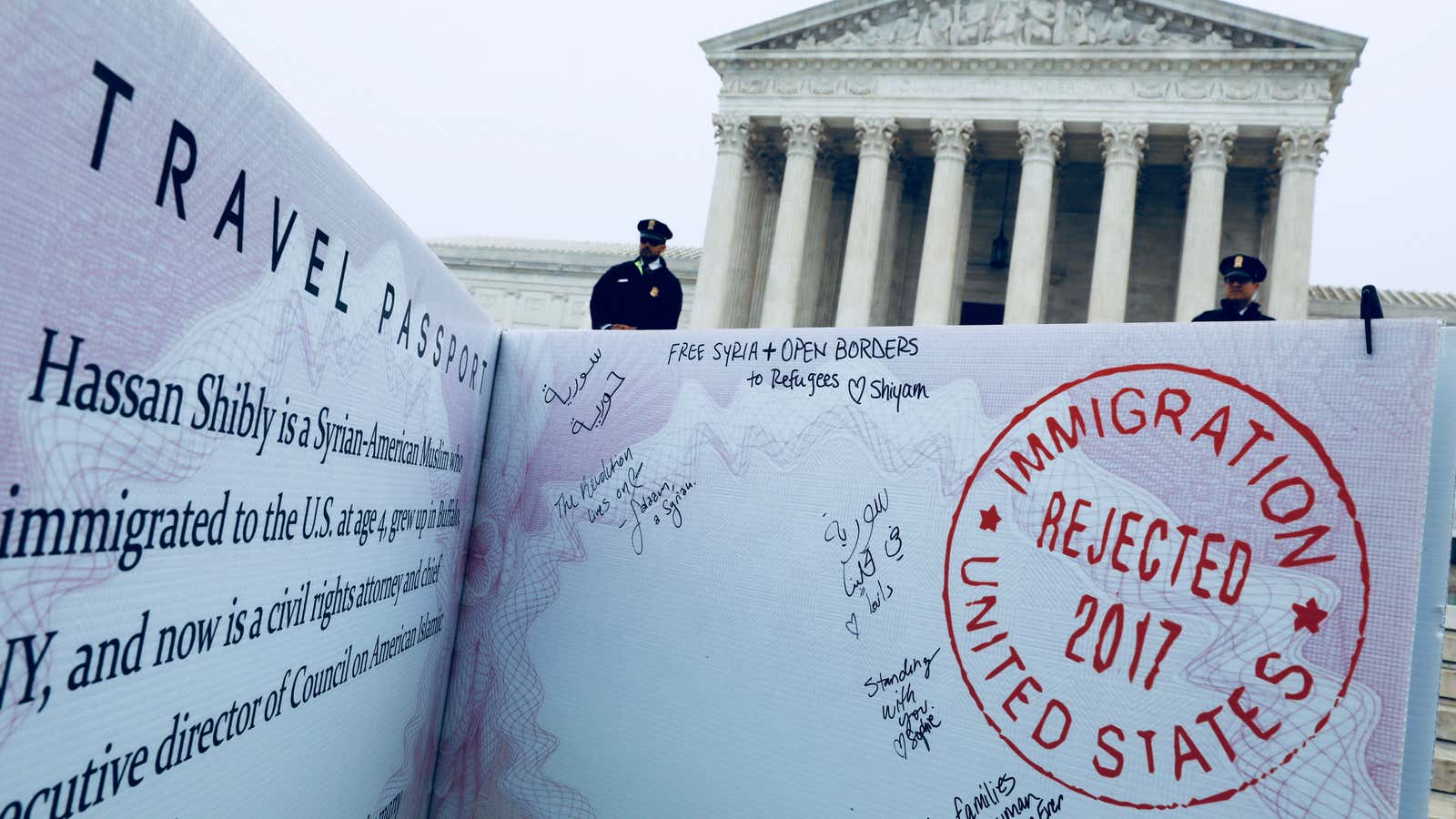

The ban in question, issued last September, was the president’s third proclamation on international travel, and barred entry to the US for citizens from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, North Korea, and Venezuela. (Two previous ban attempts, in January and March of 2017, were blocked by federal appeals courts.) In October, Hawaii challenged the ban on behalf of affected residents, arguing that it contravenes freedom of religion protected by the US Constitution. That challenge was affirmed by the Hawaii district court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, based in part on anti-Muslim tweets and statements Trump made during his campaign and while in office.

But in the majority opinion on Tuesday, chief justice John Roberts argues that those statements are irrelevant, and cites a 12-page report from the White House that outlines information-sharing, documentation, and consular-processing issues in the restricted countries. “It cannot be said that it is impossible to ‘discern a relationship to legitimate state interests’ or that the policy is ‘inexplicable by anything but animus,'” Roberts concludes.

Sotomayor, however, argues that the majority is being deliberately obtuse and ignoring the full record to reach its conclusion. She writes:

Although the majority briefly recounts a few of the statements and background events that form the basis of plaintiffs’ constitutional challenge, that highly abridged account does not tell even half of the story…The full record paints a far more harrowing picture, from which a reasonable observer would readily conclude that the Proclamation was motivated by hostility and animus toward the Muslim faith.

Sotomayor notes that Trump explicitly stated during his campaign that he would ban Muslims from entering the US because, he said, they believe in Sharia law, which poses a threat to Americans and especially women. His website even called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on,” adding that our “country cannot be the victims of the horrendous attacks by people that believe only in Jihad, and have no sense of reason or respect of human life.” Those words remained on Trump’s site for months after he took office.

By mid-2016, the president had changed his tune a bit, and was connecting the travel ban more explicitly with terrorism than religion. But Sotomayor says a change in rhetoric is not the same as a change in motive. Trump continually made statements indicating a distaste for Muslims, she notes, including as recently as November 2017. From her dissent:

[The] dispositive and narrow question here is whether a reasonable observer, presented with all “openly available data,” the text and “historical context” of the Proclamation, and the “specific sequence of events” leading to it, would conclude that the primary purpose of the Proclamation is to disfavor Islam and its adherents by excluding them from the country.

Sotomayor’s answer to the dispositive and narrow issue is, “unquestionably,” yes. “[Taking] all the relevant evidence together, a reasonable observer would conclude that the Proclamation was driven primarily by anti-Muslim animus,” she writes, noting that Trump has never taken an opportunity to retract his inflammatory comments. “The words of the President and his advisers create the strong perception that the Proclamation is contaminated by impermissible discriminatory animus against Islam and its followers.”

She also points out that in 2015, Trump justified a proposed ban by referring to Franklin D. Roosevelt, who interned Japanese-Americans during World War II. Indeed, Sotomayor compares today’s decision with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Korematsu v. US, which upheld the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II based on national security concerns. In the majority opinion, Roberts called that decision “gravely wrong the day it was decided” and “overruled in the court of history,” but Sotomayor warns that history could repeat itself.

“By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security,” she writes, “the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one ‘gravely wrong’ decision with another.”