A Chinese court is using a popular music video app to catch deadbeat borrowers

China’s naming and shaming its debt defaulters—to the accompaniment of rhythmic beats.

China’s naming and shaming its debt defaulters—to the accompaniment of rhythmic beats.

Since the launch of a blacklist for debt defaulters in China in 2013 , China’s Supreme Court has put some seven million (link in Chinese) names on it. The goal is to expose the listed individuals and companies, and better yet, get them to pay off their debts.

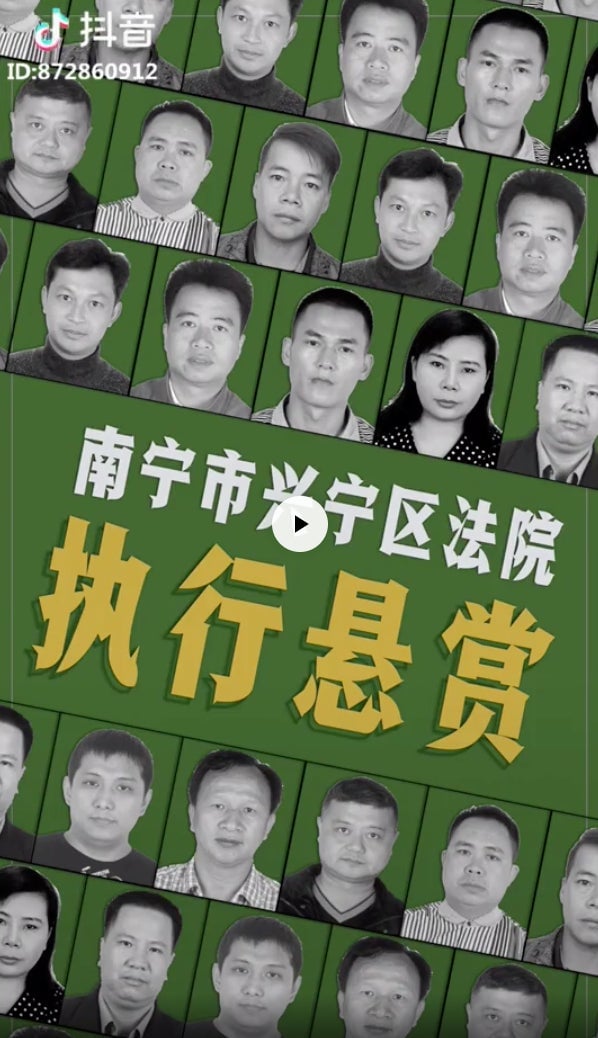

In that spirit, a local court has taken an innovative—if intrusive—approach. A district court in Nanning, the capital city of China’s southwestern Guangxi region, made short clips of images of defaulters’ faces, set to music, and shared them last month on the hugely popular Douyin mini-music video app.

And it’s working.

On June 20, a debtor showed up at the court to pay his $78,000 debt after he saw his name, head shot, and identity number featured on a Douyin clip. “I felt very ashamed, because all my friends can see this,” said the man, a frequent user of the app, according to state-run newspaper People’s Daily (link in Chinese).

Known as Tik Tok outside China, the Douyin app was the most popular iOS download globally in the first quarter of the year. The platform, whose name means “shaking music” in Chinese, is similar to American social video app Muscial.ly, letting users create short videos with various effects like looping. It has amassed some 300 million (link in Chinese) monthly active users in China since it was founded in 2016 by tech firm ByteDance, also known for popular news apps.

This was the first laolai, or “deadbeat borrower” as Chinese media refers to them, to contact the court after the video came out, according to the state-run paper. The court also offered a bounty to those who provide leads to defaulters’ whereabouts in the video.

“A big issue during the enforcement of court orders is locating these people,” said Li Jianzhong (link in Chinese), the court’s director of enforcement, told People’s Daily on June 21. ”Douyin is popular among the public and has a growing audience, if we can motivate ‘shaking friends’ to find laolai, I think there will be extraordinary effects,” said Li.

The court said it has been holding theme-planning meetings to work on the designs for its videos so as to get “more attention from internet users in a vivid and grabbing way,” according to (link in Chinese) Huang Huaying, deputy president of the court.

First opened in early June, the court’s Douyin account now has some 1,500 followers. It has released 11 videos, including two on debt defaulters, which together garnered over 500 likes, and a Chinese rap video (link in Chinese) featuring the court’s judges to promote the court’s work.

The district court isn’t the only Chinese agency that has grasped the power of Douyin, 40% of whose users are young people aged between 24 and 30 (link in Chinese). Some 500 government agencies and Communist party organizations have set up accounts on the platform, according to the latest data, as the party increasingly turns to social media to cultivate China’s highly connected millennials.

After all, as China’s president Xi Jinping told the new leadership of the Communist Youth League—which, naturally, has a Douyin account—on Sunday (July 2), it is young people who will ensure “the party’s continuous victory (link in Chinese).”