In a hall packed with business people eager to understand the nitty-gritty details of the Companies Act of 2013, a question about trusteeship was somewhat at odds.

On the podium was Sachin Pilot, the minister for corporate affairs addressing a gathering hosted by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) on Sept. 16 in Mumbai. The minister was being assisted by senior bureaucrats in answering a wide array of questions about operational implications of the new law, which updates decades-old regulations and tries to ease doing business in India.

An elderly professional in the audience asked, “Why doesn’t the new law mandate trusteeship?” The question seemed an outlier, in particular the questioner’s insistence that there is need to educate young people about the Gandhian ideal that you never really “own” wealth but merely serve as its trustee, or benevolent custodian, would commonly be deemed to be a moralistic fantasy.

And yet Joint secretary for the ministry of corporate affairs Renuka Kumar was quick to respond. Many provisions of the Act do in fact pertain to trusteeship, said Kumar. Though she did not go into details, it was assumed that she was referring to the corporate social responsibility provisions, which require companies with a net profit of 5 crore rupees ($800,000) or more to commit 2% of that profit to philanthropy.

Trusteeship is commonly, and mistakenly, equated with individual or corporate philanthropy. Instead, the essence of trusteeship has much more wide ranging implications because it is about a better alignment of business and society, profits and the larger common good.

In its essence trusteeship cannot be legislated. But as a philosophical and moral ideal it can form the basis of laws and rules—to foster a business ecosystem that makes it easier for people to strive for that ideal. Therefore, it is not surprising that the new Companies Act makes no explicit mention of trusteeship. But the ideal can and should inform the process of formulating the rules, which are still inviting comments and being revised.

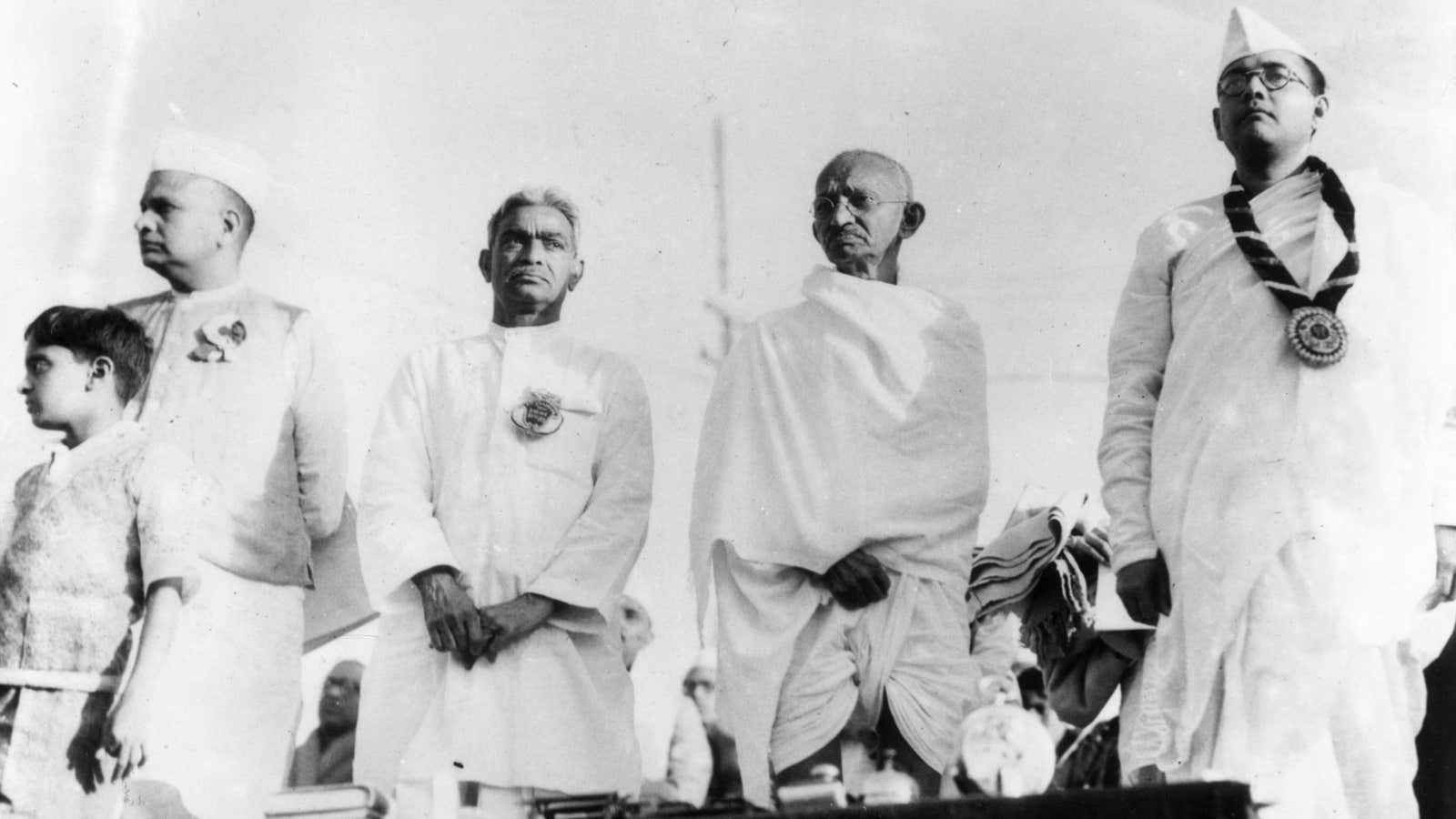

In this context, it is worthwhile to review the ideal of trusteeship—which has usually been dismissed as being too nebulous, even vague. Why then did Gandhi’s advocacy of trusteeship resonate with leaders of Indian business—notably Jamnalal Bajaj, G. D. Birla and J. R. D. Tata? Perhaps they sensed that Gandhi’s primary concern was to foster an entrepreneurial cultural in which there was no place for rule of might over right.

Globally, the world of business is now in the process of a slow but steady and positive transition to a more healthy alignment of profit-making with both the larger social good and the moral basis of life itself. This is why, a decade ago, some of the world’s largest companies joined the United Nations Global Compact and became signatories to a report titled “Who Cares Wins.” Later, in 2006, the United National Principles for Responsible Investing were instituted both on moral grounds and as a move toward better management of risks arising from social unrest and environmental decay.

Depending on how it is implemented, India’s new Companies Act could be a part of this global process, which is gathering momentum for two major reasons. One is the internal compulsion to keep markets working—rather than risk a slide into chaos due to fraud and other forms of excess. The other equally urgent imperative is for business to be responsive to rising democratic aspirations.

How then might we interrogate the claim that the new Companies Act has components that support the ideal of trusteeship?

The most minimal aspect of trusteeship is engrained in the concept of fiduciary responsibility—namely that those who manage money and resources on behalf of shareholders and investors must behave as benevolent custodians and not as self-interested parties.

For instance, the new law mandates much tighter accounting reviews and makes auditors criminally liable if they fail to report cases of fraud. Similarly, strengthening the role of independent directors and creating a greater distance between the company’s directors and auditors is also expected to enhance responsibility and prevent abuse.

But in a trusteeship framework, financial integrity is the bare minimum.

For instance, provisions empowering minority shareholders are welcome since this is likely to ensure that those in control of a company are compelled to deliver value to even the smallest retail shareholder. However, this is not enough.

It is now equally important to be fair to stakeholders. Enhancing the powers of minority shareholders can potentially move in this direction only if some shareholders do indeed keep a hawk-eye on the company’s social and environmental impacts. In Europe and in the US, such shareholder activism has compelled some companies to focus more sharply on reducing negative social and environmental impacts.

Similarly, making it compulsory to have women as company directors is not an end in itself. The presence of women will make a difference only if they bring issues of wider social responsibility, not just gender parity, into board rooms.

If the discussions at the conference in Mumbai are any indication, most of the input on the formulation of rules are likely to be the technical minutia of the act, rather than the broader vision and its implementation. Various speakers at the conference spoke about not letting the fear of a few bad eggs dominate how the rules are framed. Instead, it was urged to see competitiveness of businesses as the most important criteria for rule formation.

In contrast, that stray question about trusteeship was a reminder that competitiveness is not an end in itself. In a maturing democracy, long-term success will come not to those who derive profits from the people, but to those businesses that generate profits in ways that spread value to the people.