Dear powerful people, here’s the economic case for investing more in little kids

Dear very important person,

Dear very important person,

You’re spending your money all wrong.

As a leader of a nation, you face the immense challenge of figuring out how to allocate scarce resources. You have to make tough decisions about investing your country’s hard-earned taxes on stuff that makes people happy and positions your country to best compete in the global economy.

We know infrastructure and construction projects are always winners. Who doesn’t love new roads and faster trains? The private sector wants job training programs. Everyone wants better schools. Let’s not forget about health care and retirement programs, which are hugely expensive and often politically untouchable.

But the data suggests that governments should devote a lot more money to helping people at the very beginning—starting with pregnant women and infants, through the time that kids start school. We don’t make this case because kids are cute (although they are), or can’t lobby for themselves (although they can’t). We make this case because science and economics provides ample evidence that investing in moms, parents, and young children has a range of long-lasting benefits—ranging from higher wages to smarter kids and more equal societies.

The science of developing brains

Kids aren’t born with predestined gifts or fixed intelligence. In the first few years of life, their brain development is crazy intense (pdf)—and built in large part on the love and support that parents and caregivers can offer. Infants and young children need parents who talk to them, sing to them, and show them affection. That’s not because those things are nice to do, but because these actions form the neurological pathways that determine how children think and feel.

In other words, the environment into which a child is born dramatically affects how their brains form connections, which in turn directly influences the kinds of adults they will become. “The number of connections [in the brain] depends on the stimuli of the environment,” says Osmar Terra, the architect of the world’s largest program to support poor mothers. Poor children typically have far less stimulating environments than wealthier children. But if you improve the environment for the neediest kids in your country and support their caregivers, you can start to ameliorate the negative impacts poverty has on children’s brains and their development.

To understand just how urgent the issue is, consider the neuroscience research on what happens to kids who are deprived of the love and affection they need. Charles Nelson, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, studied 136 Romanian orphans with his team for nearly two decades to understand what happens when the fundamental bond between children and their parents is broken. They found that children separated from their parents in the first two years of life scored lower on IQ tests when they were older. The orphans’ ability to regulate their emotions and impulses was worse, and the kids’ stress reaction systems seemed broken: things that would cause a typically-developing child to feel anxiety would not have the same effect on them.

MRI scans showed that by age eight, these children had less gray and white matter in their brains than children raised by their own families. (White matter is the “information super highway” that moves information around, while gray matter is the brain’s central processor.) The MRI research was only based on a sample of 69 of the orphans, but the results are still intriguing.

“Children who experience profound neglect early in life, if you don’t reverse that by the age of two, the chance they will end up with poor development outcomes is high,” Nelson told Quartz.

The good news is that we also know more today about how to build resilience in children, especially those who have faced trauma or extreme adversity. Kathy Hirsh Pasek, a senior fellow at the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, writes for the Brookings Institution:

First and foremost is the support and care of an adult who is mentally and physically able to function. Trauma affects parents too and handing a traumatized child to a traumatized parent is a risk to both of their functioning. Mental health services for the parents and children and living conditions that allow families to function are proven conditions to support child resilience, increasing the chances they will grow up to be socially competent, self-reliant, to have self-control and succeed in school.

So you have a choice. Some children who face neglect and deep adversity will face the aftershocks of this as teenagers and young adults, potentially drawn to drugs or gangs, at risk of dropping out of school and committing crimes, and more likely to go to jail (all of which are expensive to deal with, and represent a significant loss of human potential). Or you could get a jump start by investing to support parents and poor families early on. Your pick.

The economics of early childhood intervention

So maybe you think the brain science is a slam dunk. But science supports lots of things. You want to talk returns. Fair enough. Here are a few studies that show how investing in poor children and their moms pays off. The studies are small, but the potential they reveal is enormous.

The Highscope/Perry Project

The Highscope/Perry Project studied 123 children living in poverty in Ypsilanti, Michigan. From 1962–1967, at ages three and four, the kids were randomly divided into two groups. One group attended a high-quality preschool program, and a comparison group who received no preschool program. The kids were tracked until they were 40.

The effects were dramatic: kids who’d attended the preschool made more money and committed fewer crimes. They were more likely to hold a job and more likely to have graduated from high school than the group that didn’t have a preschool education.

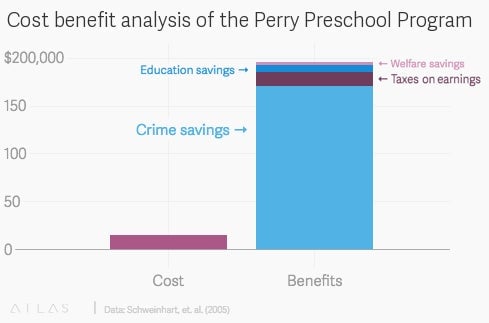

The program was expensive, and the group was small. But according to a cost-benefit analysis of the study, the experiment paid off:

Investing a little over $15,00 in the children resulted in total public benefits of nearly $200,000—that is, money saved by lower school dropout rates and gains from better jobs and fewer crimes. Those estimates clearly involve many assumptions, but even if they are half right, that appears to be money well spent.

The Jamaica experiment

Another widely cited, albeit very small, study is a program started in the 1970s in Jamaica by Sally Grantham-McGregor, an emeritus professor of international child health at University College London and University of the West Indies, and Christine Powell, from the University of the West Indies. The pair designed programs that sent doctors and nurses to visit poor mothers in Kingston, Jamaica, every week in their homes for two years, bringing toys and books that would help parents become better teachers to their babies and to increase stimulation and play.

The resulting studies found that children whose mothers received coaching made significant developmental gains—and not just in the short term. Twenty-two years later, the kids from one group who had received those home visits as young children not only had higher scores on tests of reading, math, and general knowledge, they also stayed in school longer. They were less likely to exhibit violent behavior, less likely to experience depression, and had better social skills. They also earned 25% more on average than a control group of kids whose mothers had not received the coaching.

“If we want to attack poverty, the place to start is very early in life,” says Paul Gertler, an economist who studied the long-term effects of the Jamaica program. Compared to the cost of unemployment benefits or other social safety net programs, “getting it right to start with is cheaper,” he said.

The Abecedarian study

Finally, there is the Abecedarian approach, which offers programs grounded in childhood development research, delivered by trained staff, to poor families without much education. Started in the 1970s in North Carolina, the researchers created a program that emphasized positive interactions with adults—what scientists now call serve and return—a curriculum that emphasized using a lot of language (poor children hear significantly less words than rich ones) and a focus on health and safety for kids. It has now been used in various countries and settings, including three longitudinal studies which were recently evaluated here.

The results are kind of mind-blowing.

The study measured 111 kids, many over the course of 45 years. At every step along the way, they fared better than the control group. They scored better throughout school in reading and math at ages eight, 12, 15, and 21, repeated far fewer grades, and were far less likely to be placed in special education (12% enrollment in special-ed classes, compared to 48% in the control group). Since special ed costs 2.5 times that of regular education in the US, this is a major costs savings.

There’s more…much more:

- By age 19, fewer had become parents themselves (25% versus 45% in the control group)

- At age 21, they were more likely to be employed or in higher education (67% compared to 41% in the control group)

- At 30, they were four times more likely than the control group to have graduated from college, and more likely to be employed full-time and in good health

- At 30, they were less likely to be using the welfare system

- At 35, 25% of the control group had metabolic syndrome (a cluster of effects that increase your risk of heart disease, stroke and diabetes), compared to none in the treatment group

- In their early 40s, the Abecedarian participants had structural and functional MRIs of their brains to see if their brains developed differently compared to the control group. They did. Only 29 in the treatment group were available to be scanned, and 18 in the control, but those scanned showed significant differences in two of five areas of the brain associated with language

The parents of the children involved in the program fared better as well: Teen mothers who were in the treatment group were more likely to stay in school by the time their kids were 15 (80% compared to 28% for the control group) and more likely to be employed. And in a finding that wowed the researchers, they were more likely to be alive: 29% of the mothers in the control group died before their children were 40, compared to 10% of mothers whose children received the educational treatment.

In education research, an effect size of 0.25 and higher is generally considered good. In the Abecedarian Project, the effect sizes ranged from 0.73 up to 1.45 for children from the ages of 18 months to 4.5 years; the average was 1.08.

Joseph Sparling, who helped build the original program and who is a senior scientist emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says the program showed that we can use the first five years of life—when the brain is the most flexible and adaptable and capable—much more effectively. Young children “are ready to learn different and complex things—an entire language, how to solve problems,” he said. “We don’t necessarily use that time as wisely as we can.”

Two other longitudinal studies found similar benefits for the Abecedarian program: Project CARE, a sample of 64 kids in North Carolina, and the Infant Health and Development Program, which focused on infants born prematurely and at low birth weights. That study was initiated in 1984, conducted at eight sites in the US, and lasted three years. The results were profound: for the 377 children in the treatment group, the program “leveled the playing field,” enabling them to perform at levels slightly higher (IQs of 104–107) than the national average at these years of age.

Like Perry, the Abecedarian studies were very small—though there have been many. But the savings, at least for the universe of children who have been followed up to 40 years, were huge. The question is, do you have the leadership to put in place a program with benefits that accrue over decades?

A range of benefits

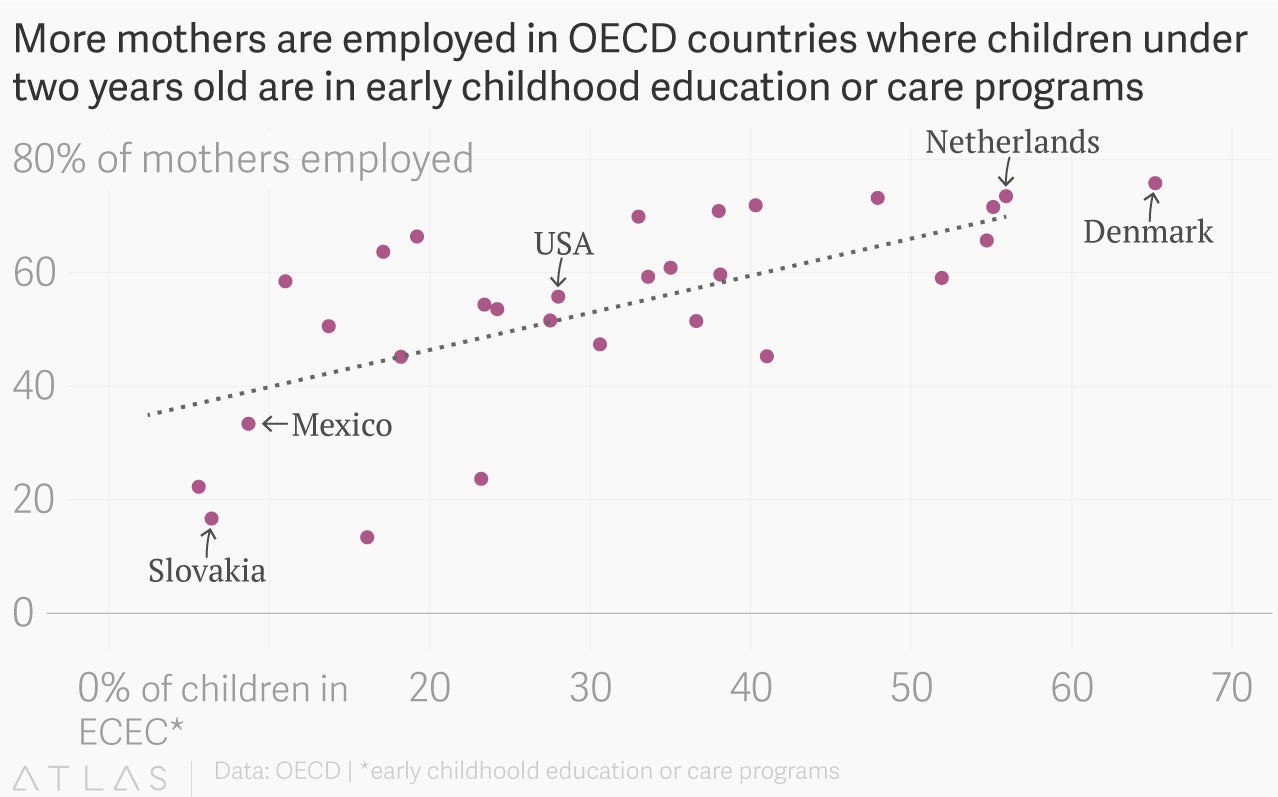

Not surprisingly, providing better and more affordable child-care options leads to more women working. This is great for growing the economy and improving gender equality. For countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the data show that more kids under two in early childhood education or care programs, the more mothers work. The relationship is large. In the average country where at least 50% of kids are in programs, over nearly 70% of mothers work. In contrast, in the average where less than 20% of kids are in programs, only about 40% of mother works.

And there’s another reason to invest in better child care: if it’s too expensive to access, people may wind up having fewer kids. And that’s a problem if you are one of the many countries in the world facing birth rates so low that the population is falling.

In the US, for example, in 2017, the number of births for every 1,000 women of childbearing age clocked in at 60.2 in 2017, a record low. The total fertility rate — which estimates how many children women will have based on current patterns — is down to 1.8, below the replacement level in developed countries of 2.1.

The New York Times recently surveyed 1,858 American men and women between the ages 20 to 45 about their baby-making plans. Almost one-third (31%) of those who said they didn’t want children or weren’t sure cited the expense of child care as a factor in their decision.

Moreover, investing in early childhood may well lead to better academic performance later on. An OECD analysis found that in most countries, even after accounting for socioeconomic background, students who attended early childhood education programs for two years or more scored higher on a standardized international science test than those who attended for less than two years.

And yet few countries seem to be focusing on the need to invest in kids before they get to school. While this chart only considers a few countries, it is a pattern repeated all over the world:

So what should you do?

According to Dave Evans, an economist at the World Bank who has studied the evidence for early childhood, there’s strong evidence on the benefits of small programs, but less strong evidence for larger ones. In all, he says, the collective body of research for early-childhood programs makes “a pretty strong case that if you can do it right, it’s your best investment.”

He said that world leaders have already come a long way: It’s now pretty much accepted that governments should take action, and that investing in moms and young children has high returns. “The question is about competing priorities and capacity, not whether we should do this,” Evans said.

If that’s not enough to convince you, consider Sparling’s take. He says that investing in early childhood allows us to solve two issues: Social inequity, and the need for human empowerment. “We need to enable every person to reach his own full potential and not be limited so he can live a satisfying life.”

Thanks for your consideration,

A few concerned journalists

Read more from our series on Rewiring Childhood. This reporting is part of a series supported by a grant from the Bernard van Leer Foundation. The author’s views are not necessarily those of the Bernard van Leer Foundation.