Starbucks announced plans to eliminate plastic straws in all its 28,000 outlets by 2020. Unveiling photographs of a new lid cup design today, the world’s largest beverage chain estimates that it will save a billion straws each year.

Many sustainability experts and environment advocates cheered Starbuck’s planet-saving initiative as a significant milestone in the campaign to combat the 8 million metric tons of new plastic waste entering the world’s oceans each year.

But in the bid to design alternatives to straws, there’s one oft-ignored population that will be negatively affected when the much-maligned drinking devices aren’t so readily available. For many people with physical disabilities, straws “are vital for independent living.”

Writing on the Greenpeace blog, Jamie Szymkowiak, co-founder of the Scottish disability rights nonprofit One in Five, explains why disposable plastic straws, for the time being, is still the best option for many people with disabilities:

A soggy paper straw increases the risk of choking. Most paper and silicone alternatives are not flexible, and this is an important feature for people with mobility related impairments. Metal, glass and bamboo straws present obvious dangers for people who have difficulty controlling their bite, as well as those with neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s. Some disabled people use straws when drinking coffee or eating soup, yet most of the alternatives, including the leading biodegradable straw, are not suitable for drinks over 40°C. In addition, re-useable straws in public places are not always hygienic or easy to clean.

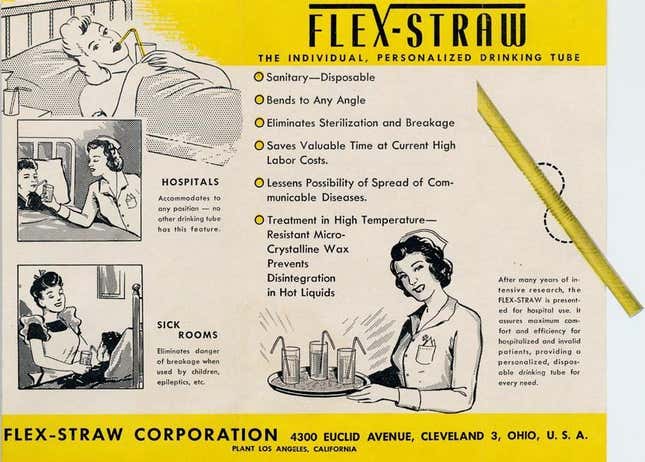

To Szymkowiak’s point, bendy plastic straws were originally used as adaptive technology in hospitals. In the late 1940s, inventor Joseph B. Friedman sold the disposable “Flex-Straw” (or “personalized drinking tube”) as a tool to help reclined patients drink from a cup. As the Flex-Straw advertisement shows, they were sanitary, cheap, sturdy, temperature-resistant and suited for children and epilepsy patients.

Friedman’s genius invention—initially devised to help his young daughter sip a milkshake on her own—is championed as an icon of ”universal design”—a principle that ensures that all designed objects and systems are accessible and pleasing to everyone regardless of age, economic status or physical abilities.

Szymkowiak clarifies that meeting the requirements of disabled populations doesn’t need to kill the planet. He suggests that instead of banishing straws altogether, companies should continue researching wisely-designed alternatives that will work for everyone. ”As we move to ridding our oceans, beaches and parks of unnecessary single-use plastics, disabled people shouldn’t be used as a scapegoat by large corporations, or governments, unwilling to push suppliers and manufacturers to produce a better solution,” he writes. “We must all work together to demand an environmentally friendly solution that meets all our needs, including those of disabled people.”

Starbucks tells Quartz that they’re thinking of customers with disabilities, as they move to eliminate straws at their global outlets. A spokesperson says they plan to offer straws made of an “alternative material” for people who need it.