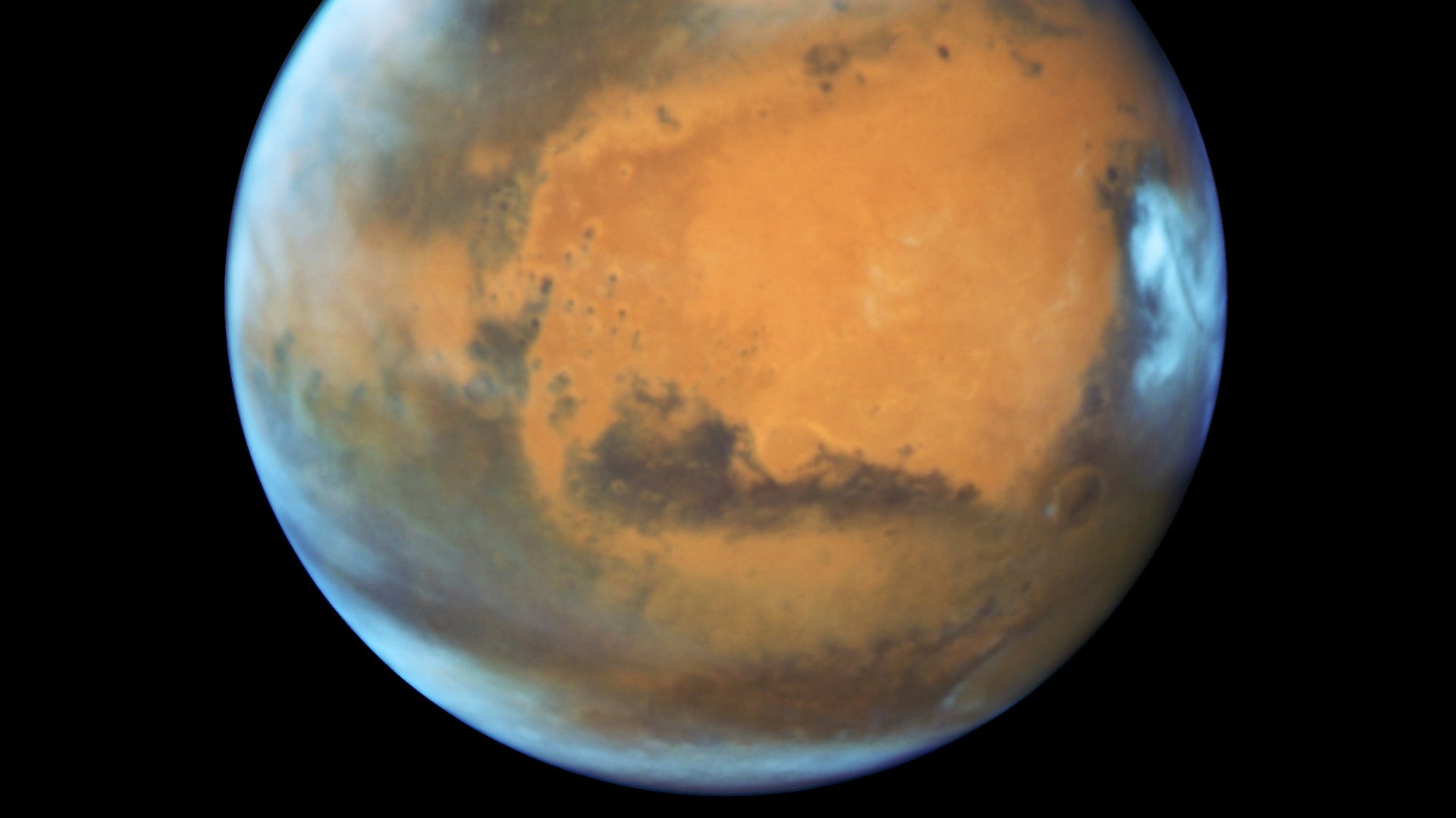

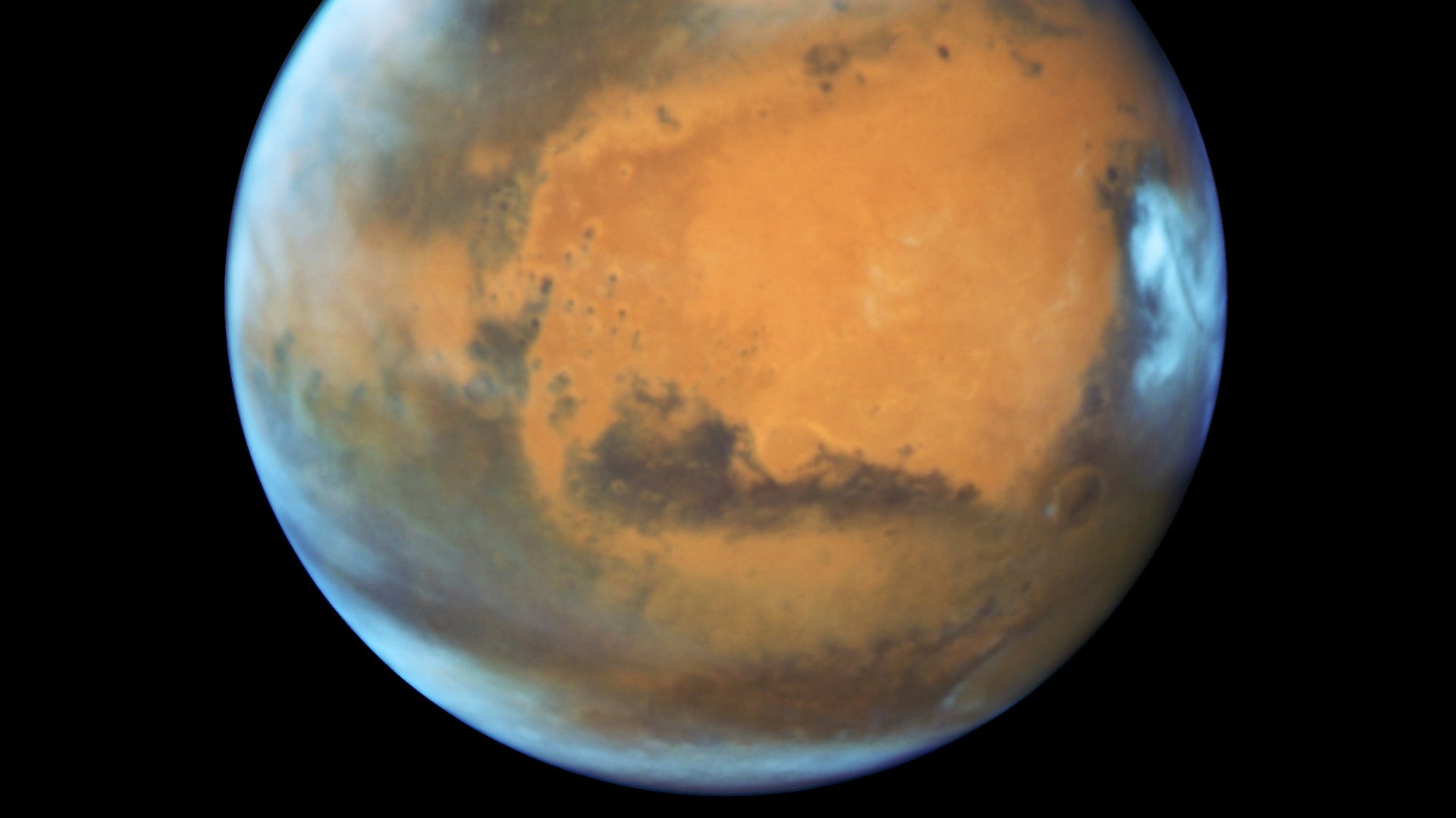

The catch to exploring water on Mars (and anywhere else in space)

Scientists believe they have found an underground lake of liquid water on Mars, which has space explorers all the more eager to visit.

Scientists believe they have found an underground lake of liquid water on Mars, which has space explorers all the more eager to visit.

“Seems like a good time to start working on landing BFR,” tweeted the SpaceX engineer in charge of making sure Elon Musk’s next big rocket, the Big Falcon Rocket, can safely reach Martian soil. NASA is already planning a mission to return samples from Mars in 2020. The agency is also plotting an $8 billion mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa that could fly through plumes of water ejected by the icy planetoid.

Water on Mars, or anywhere in space, is exciting for two reasons: First, with the right technology, humans could purify it to drink, and use it to produce oxygen and even rocket fuel, making long-term exploration far more feasible. Second, water offers the tantalizing possibility of extraterrestrial life: Scientists think life on other planets could evolve much like life on earth—out of the ocean.

But that’s part of the problem: Since microbes on our planet love water, human expeditions to another planet could contaminate it, potentially leading to a solar system-scale invasive species. That would in turn screw-up scientific research—and, if actual extra-terrestrial life exists, potentially disrupt its ecosystem.

Advocates of space exploration often reach for comparisons to Europe’s first encounters with the American continents as a metaphor for their ambitions. But the European explorers carried with them bacteria that wiped out indigenous peoples, even as they encountered new illnesses that decimated their own delegations. Scientists hope to avoid such unintended consequences on the high frontier.

A global pact to avoid “harmful contamination”

Since the United States began plotting its assault on the moon in the 1960s, scientists have fretted about these possibilities. These worries were codified in the famous United Nations outer space treaty in 1967. Article IX requires that spacefaring nations traveling to celestial bodies “avoid their harmful contamination…and, where necessary, shall adopt appropriate measures for this purpose.”

But “appropriate” is essentially up to whoever is interpreting the treaty. “Each space agency, each country, adopts different standards, whether more or less stringent,” explains Michael Listner, an attorney who specializes in space law.

In recent years, those standards have become more relevant: Scientists are increasingly confident that ice may be found on the lunar surface, that moons like Europa contain large bodies of water underneath thick ice caps, and now that Mars may have liquid water as well. Meanwhile, a new generation of space technology companies are developing cheaper transportation systems and calling for more ambitious missions.

“With commercial space and Mr. Musk planning on going to Mars, they re-opened this whole debate again,” Listner says. “NASA is going back and looking at the current planetary protection protocols and saying, based on what we’ve learned from experience, now, is our interpretation of our Article IX obligations correct?”

In July, the National Academy of Sciences released a report urging the space agency to modernize and standardize its exploration protocols. It worried in part that NASA currently lacks the infrastructure to keep up with the latest biotechnology and the work of ensuring any private exploration missions launched from the US uphold international treaty obligations.

How do you keep space clean?

The Committee on Space Research, or COSPAR, is the global forum where space exploration agencies and scientists try to find a consensus around planetary protection. One focus is on a “bioburden standard”—how many microbes are on a spacecraft when it leaves earth, measured by the spores of heat-resistant bacteria found in samples taken on the vehicle. Under current standards (pdf), anything landing on Mars to see if life exists must have less than 30 spores in such samples.

Ensuring the Mars Curiosity rover, which landed in 2012, met the standard was no small task. Seven NASA technicians took 47,997 samples from the vehicle, heating them and putting them in petri dishes to analyze the results. Meeting this level of sanitization requires clean rooms and “bunny suits”—those full-body anti-contamination outfits—as well as frequent cleaning with solvents like ethanol. To go further, spacecraft can be heated in an oven in dry conditions, or exposed to hydrogen peroxide vapor, among other techniques.

That kind of painstaking work may not appeal to companies eager to get down to business in space, whether setting up lunar habitats or attempting to visit Mars. But, whether or not they worry about science themselves, those entrepreneurs are heavily dependent on NASA for assistance and funding.

“We’ve got to look at this from both sides,” Listner says. “The scientific view of it is be careful not to contaminate things, [but] we can’t be afraid we’re going to trip over a microbe every time we want to do something in outer space.”

The sooner that the US and the rest of the world’s space powers agree on how to understand, upgrade and enforce these protocols, the better, because the capacity of people to do stuff in the solar system is beginning to outstrip the legal framework to protect it.

“There has been lots of discussions about ‘terraforming’ Mars to release the trapped water and possibly create an Earth-like environment there,” James Dunstan, another attorney who focuses on space law, told Quartz. “I don’t see anything in Article IX (or elsewhere in the treaties) that legally would prohibit it.”