A battle is quietly being waged over the United States’ weather data—and its ability to predict its future.

In his first exclusively audio story, Michael Lewis dives into the wonk-filled world of weather forecasting: the researchers who collect and study the data; the citizens who benefit from, or actively ignore, forecasts; and the powers that threaten the entire flow of information. His conclusion: The US’s publicly funded weather forecasting agency, the national weather service, and the data it collects, are under threat from a pro-business, anti-open-data administration.

“The Coming Storm” is a very brief Audible-produced audiobook (about a fifth of the length of other Lewis books). Narrated by Lewis, it comes out today, July 31. Along with other stories forthcoming on Audible and previously published in Vanity Fair, it will be part of Lewis’ next full-length print book, The Fifth Risk, coming out this October.

True to form, the bestselling author of The Big Short makes beleaguered heroes out of the government researchers and villains of those who would disrupt their mission. These are Lewisian villains: profit-hungry phonies who endanger the quality of scientific research by arguing that if money can be made from forecast data, the government shouldn’t give it away for free.

Take Barry Myers.

Myers is the CEO of private forecasting company Accuweather and Trump’s pick to take over the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a part of the department of commerce, and the agency that oversees the weather service. (Myers was nominated in October but has yet to be confirmed, leaving the agency without a confirmed leader for over a year.)

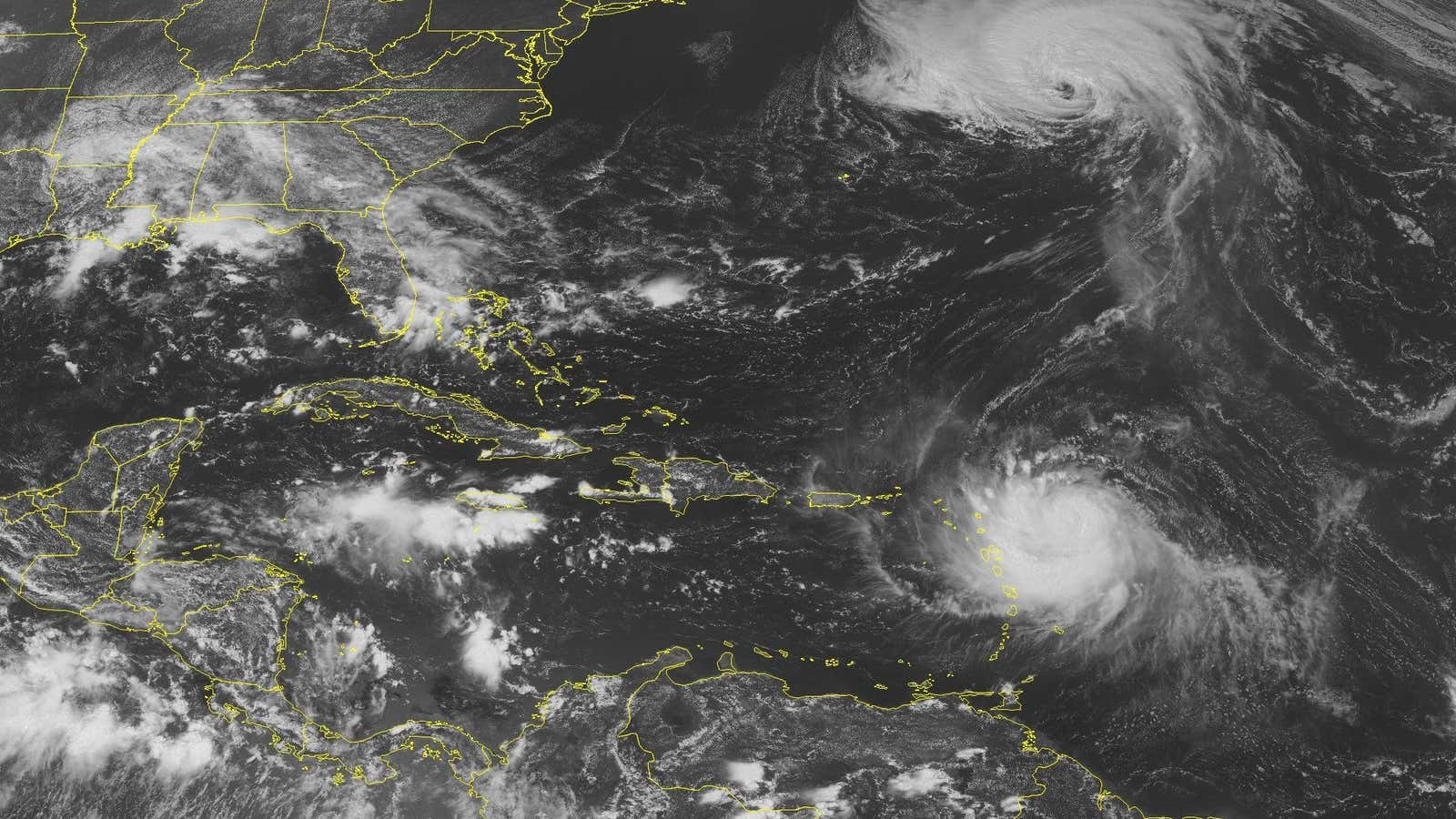

Lewis emphasizes the importance of this little-publicized agency: “[NOAA] had collected all the climate and weather data going back to the recordings made at Monticello by Thomas Jefferson. Without that data, and the weather service that made sense of it, no plane would fly, no bridge would be built, and no war would be fought—at least not well,” he says. The weather service’s data is free to the public, and proprietary models used by private weather companies, including Accuweather, are powered by its raw data.

“By the 1990s, Barry Myers was arguing with a straight face that the national weather service should be, with one exception, entirely forbidden from delivering any weather-related knowledge to any American who might otherwise wind up a paying customer of Accuweather,” says Lewis. “The exception was when human life and property was at stake.”

In 2005, Rick Santorum, to whom Myers and his brother are campaign donors, drafted a bill that explicitly prevented the national weather service from providing services or creating products that the private sector could. Though the bill died, Bloomberg last month described that effort as “the boldest attempt by the Myers family in a three-decade quest to undercut the scope of the service’s mission.”

Myers declined to comment for this story. At his confirmation hearing, he promised he and his wife would sell all their shares in Accuweather and related companies, if appointed to lead NOAA. He also said:

I know what peer reviewed research looks like. And scientists should be free to operate in that kind of environment. They need to subject their research obviously to peer review so other scientists can weigh in on it. But once that process is completed that information should be made available to all.

But Lewis argues that Myers’s history suggests he will disappear more of the federal government’s publicly available data, once confirmed. The reason that there is no app from the public weather service, says Lewis, is the result of Myers’ lobbying. (He further argues that Myers is not fit for the job anyway, casting shade on his lack of scientific chops—Myers is a lawyer—and Accuweather itself, which has collected data from its app users without their permission and introduced a scientifically preposterous 90-day forecast.)

The story meanders at points, but does its job: With narrative acuity Lewis dramatizes an obscure topic and creates a digestible David and Goliath story that pits data nerds against capitalist lobbyists.