When the Mexican-American War concluded in 1848, those living in the Rio Grande Valley suddenly found themselves on the US side of the border. Most received US citizenship and decided to stay. By the late 1880s, more than 80% of the population of the Valley—which by then had become a four-county region in South Texas—still identified as “Mexicans” on the US census. They retained the small plots of land that they’d received through Spanish land grants and passed them on from generation to the next and while they paid taxes in US dollars, the region continued to be thoroughly dominated by Mexican culture. Trade still routinely took place in pesos and Spanish was the common tongue.

But by 1920, the region had undergone a dramatic transformation. Traditional ranching all but ended and large-scale commercial farming began to take hold. Today, the Valley’s population is about 90% Latino, but the vast majority of farmland—and as a result, water—is still controlled by Anglos.

A series of events (pdf) drove the change in land ownership in the late 1800s and 1900s. Droughts that struck the Valley sporadically in the 1880s intensified in the early 1890s. According to Alicia Dewey, a history professor at Biola University in California who has studied the early history of the Valley, thousands of cattle died, and many of the region’s Tejano ranchers sold their remaining livestock. As a result, many went into debt to lenders and had no choice but to sell their land. Some Tejano ranchers ended up becoming farmworkers on the land they previously owned. With the arrival of the railroad, the land loss only accelerated. In 1904, the first section of the St. Louis, Brownsville, and Mexico Railway was completed, linking the Valley to the port cities of Corpus Christi area and Houston.

Suddenly, the Valley was connected to large markets across the country. As word spread that the railroad was coming to the Valley, land prices in the region shot up further, increasing property taxes, and forcing many remaining Tejano landowners to sell.

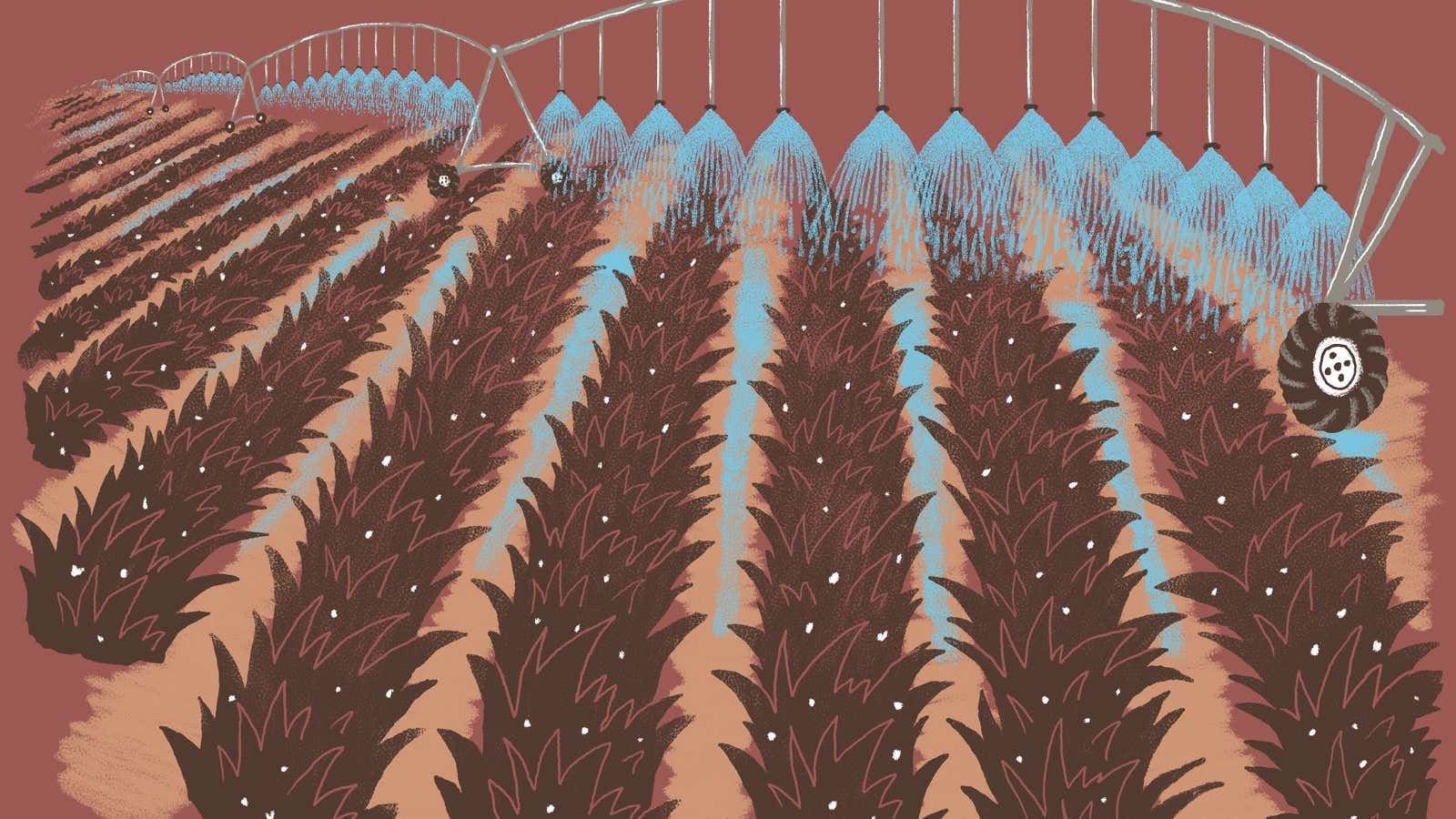

In the early 1900s, some of the new Anglo landowners also began setting up irrigation companies to build canals to move irrigation water from the Rio Grande to nearby farms. To fund the development, the farmers went about getting voter approval for taxing entities (pdf) that could issue government-backed debt. The availability of cheap, plentiful water for agriculture in turn further drove up property values. Land values in Hidalgo County surged from just $0.25 an acre in 1903, before the railroads were completed, to $50 an acre in 1906. By 1910, an acre was selling for $300.

With the increase in property values, taxes shot up further, too, and many of the remaining cash-poor, land-rich Tejanos saw the banks foreclose on their properties Since the law at the time didn’t require that foreclosed land be auctioned at market value, land that was worth thousands of dollars was often sold—predominantly to Anglos—for just the tax arrears.

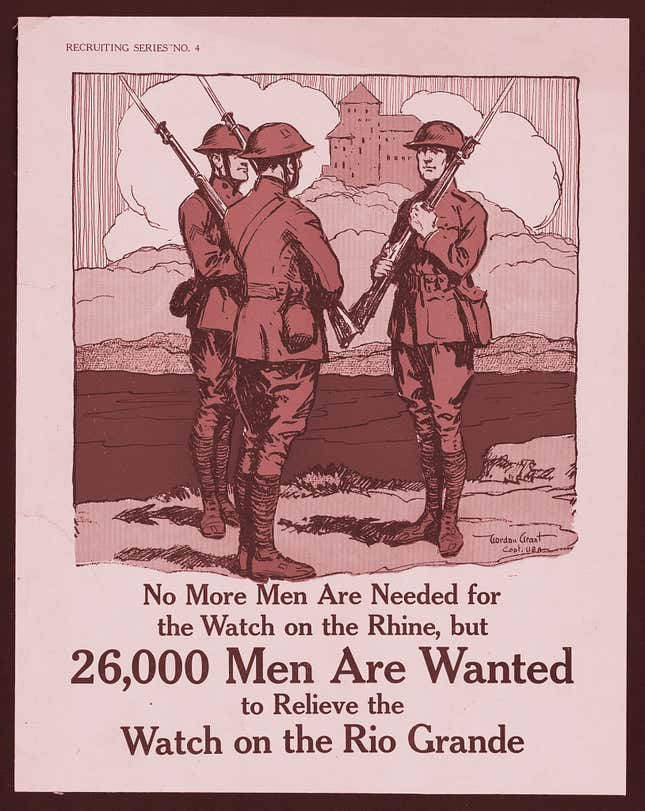

The current dominance of Anglo farmers is also the result of a legacy of racism and segregation through “Juan Crow” laws in place at the turn of the 20th century. In some cases, Tejanos were literally driven off their land at gunpoint. In 1915, police officers found a copy of the Plan de San Diego, a document calling on American residents of Mexican ethnicity to rise up and revolt against the government. In response, local lawmen and vigilantes began killing prominent Tejano businessmen and the Texas Rangers, a paramilitary group that later transformed into a statewide law enforcement agency, were deployed. Instead of ending the raids and violence, the rangers joined the local vigilantes and indiscriminately killed “suspected Mexicans,” according to a US army report. Anglo landowners took advantage of the animosity toward Tejanos and used fear and intimidation to steal their land. Because many Tejanos had come into their property through Spanish land grants—often secured with a handshake or old, obscure documents—they found it difficult to prove ownership.

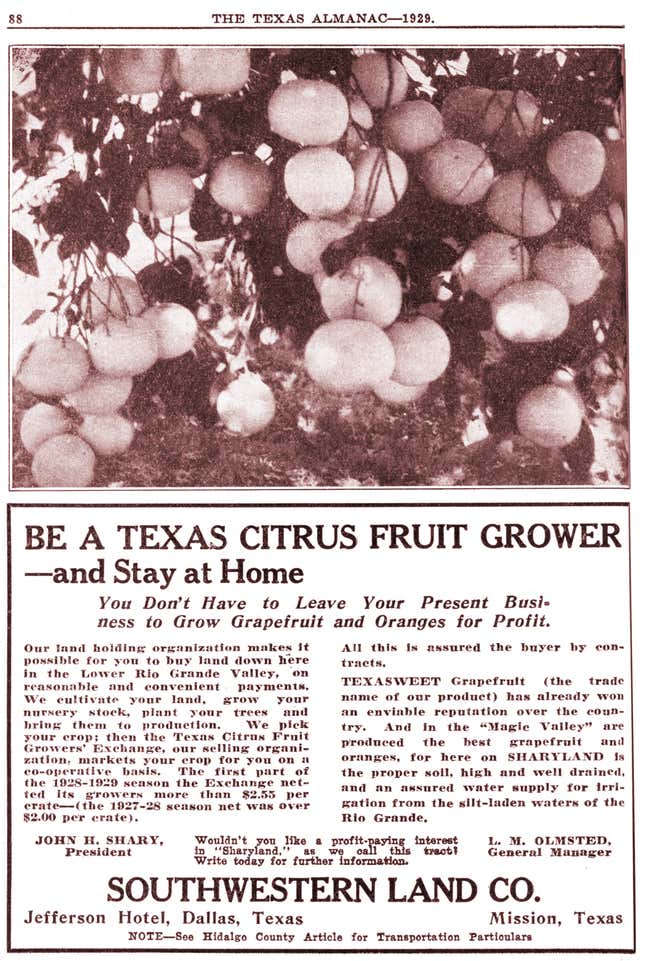

At the same time, land developers and boosters were spreading the word in Iowa, Wisconsin, the Dakotas, and other Midwestern states that the Rio Grande Valley was paradise on Earth for farmers. Through pamphlets and other written literature, they advertised cheap land and plentiful water from the Rio Grande, describing the region as a “Magic Valley.” The climate was temperate, they said, and what’s more, the “Mexicans” who lived there were docile, hardworking, didn’t resent white men, and would provide cheap labor for less than a $1 a day!

The boosters brought trainloads of potential settlers from all over the Midwest, selling them a vision of the Valley that was simply false. For one, summers are brutally hot. Plus, Tejanos hadn’t exactly welcomed the violent Anglo settlement in the region; there had been several uprisings to resist the land usurpations. But through high-pressure sales tactics, and sometimes outright trickery, the developers succeeded in selling thousands of acres of land to farmers from the Midwest.

In Cameron and Hidalgo counties alone, more than 187,000 acres of land were transferred from Tejanos to Anglos from 1910 to 1920. Just 24,000 acres were being irrigated in the Valley in 1908; that number skyrocketed to 400,000 by 1930, the vast majority owned by Anglos.

Meanwhile, a large number of Mexican nationals were crossing the border to the US side of the Valley. The decade-long Mexican revolution from 1910 to 1920 forced thousands of Mexicans to flee north to the US. Historians estimate that almost 900,000 Mexicans settled in the US in that decade; most stayed in South Texas and worked in the fields on Anglo-run farms.

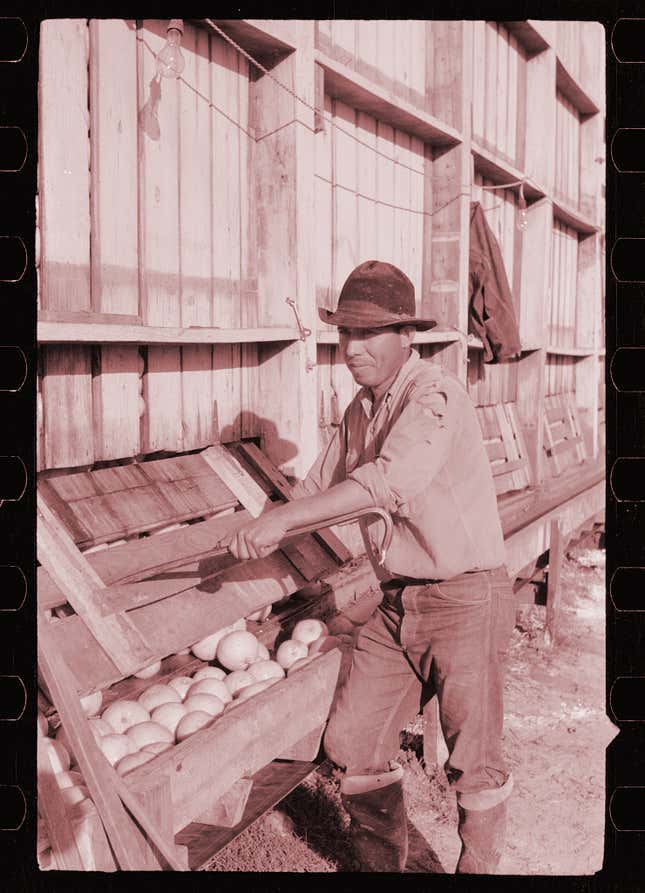

Prior to the development of irrigation canals in the Valley, the few Tejano farmers who owned small plots of land adjacent to the Rio Grande predominantly grew vegetables and cotton—crops that can be cultivated on rainfall alone. The exact history of how citrus, which would go on to become the region’s biggest crop, came to the Valley is unclear. Some historians believe Spanish missionaries in the mid-1800s gave orange seeds to a prominent ranching family in Hidalgo County. But there are also accounts of Mexican families bringing oranges as presents on visits to relatives in the Valley around the same time. In any case, large-scale citrus farming didn’t begin until the construction of irrigation canals that could move water inland to water the thirsty orchards.

Once the farmers in the region secured access to Rio Grande water, the rest fell into place. The land close to the river was sandy, loamy, and fertile, perfect for planting grapefruit and oranges. The subtropical climate, similar to that of California and Florida, meant a long growing season. Their location in the middle of the country also gave Valley farmers a competitive advantage over those two coastal states.

By the 1920s, the citrus industry had taken off. In 1925, about 5,000 tons of citrus fruit were exported from the Valley annually. The region’s citrus industry survived several disastrous freezes in the 1940s and 1950s and suffered some loss in acreage but continued to grow.

Farmers in the Valley also took to growing sugarcane, cotton, and a number of vegetables, including onion, cabbage, and carrots. Today, the Valley’s citrus industry is responsible for producing about 250,000 tons of grapefruit, oranges, tangerines, and lemons every year. Though the Texas citrus industry accounts for less than 4% of nationwide production— California and Florida lead with 4 million and 3.5 million tons respectively—it’s still a significant economic driver in the Valley.

And thanks to the region’s sugar-cane farmers, Texas is also one of only four states that produces sugar from sugar cane—the Valley produces an average of 150,000 tons of sugar every year. That is about 10% of Florida’s annual sugar production from cane.

Agricultural, and in particular citrus, is the pride of the Rio Grande Valley, but the region’s success is still tainted by the legacy of land appropriations, anti-Mexican violence, and segregation. Even though the vast majority of the Valley’s residents are Latino, about two-thirds of farmland is owned by white residents. As a result, the control of land and water still squarely remains in the hands of white farmers.

This is the sixth article in a series on border water and climate change, the result of a partnership between Quartz and the Texas Observer. Part of the reporting for this project was supported with a collaborative reporting grant from the Center for Cooperative Media.