First Argentina. Now Turkey. The next country to face a financial crisis could be any one of a slew of emerging-market economies that have grown dangerously dependent on borrowing in dollars and other foreign currencies.

As of the end of 2017, corporations in emerging markets owed $3.7 trillion in dollar debt, nearly twice the amount they owed in 2008, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Analogies to 1997’s Asian financial crisis and Mexico’s “Tequila” crisis of 1994 abound. But the roots of emerging-market crises lie further back in the history books. In The Volatility Machine: Emerging Economics and the Threat of Financial Collapse, finance professor Michael Pettis urges us to look to Europe in the early 1800s, just after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The financial conditions and innovations that gave rise to the first truly global crisis, in 1825, are in many ways similar to the conditions that have led Turkey and Argentina to their current precarious states.

For France, the year 1815 started out calm enough. Napoleon Bonaparte was in far-away Elba off the Tuscan coast, having been exiled to the island by a coalition of European powers. But in February, Napoleon escaped—and wasted no time in going back to attacking coalition forces in what became known as the Hundred Days War.

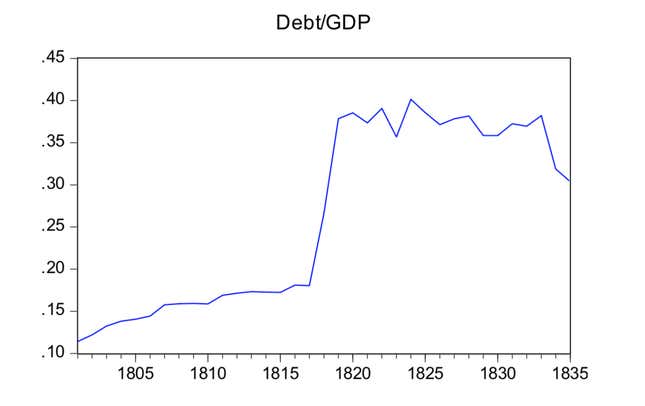

On the evening of June 18th, English and Prussian armies surprised Napoleon with a decisive defeat at Waterloo. When the ink dried on the Treaties of Paris in late November, France suddenly owed the rest of Europe a heck of a lot of money. As reparations for the Hundred Days War, the victors slapped France with a bill of 700 million francs, to be paid over the next five years—equal to around 20% of France’s annual GDP. (You can see how sharp that increase was in the chart below.)

That was a tough ask for France. Its war-sacked treasury was virtually bare. Its credibility was similarly void, having defaulted on previous sovereign debts—suggesting it would have to pay nosebleed rates on debt to lure buyers to take on the risk. Indeed, in 1816, it was forced to issue short-term treasury bonds at the steep rate of 12%, according to research (pdf, p.13) by economist Eugene N. White.

Somehow, though, France prevailed—a feat that not only restored its public finances, but that also had much bigger global implications. The unexpected foreign enthusiasm for French bonds sold to pay the war debts created a borderless surge of liquidity—a crucial early component of what would soon become the first global lending boom.

The big rentes bull market

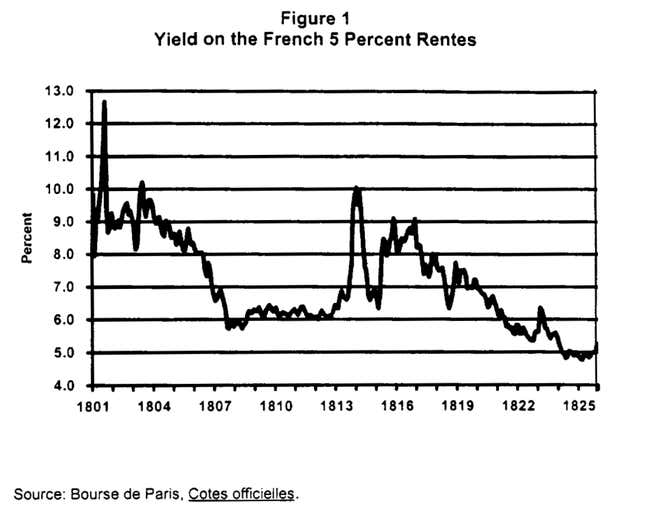

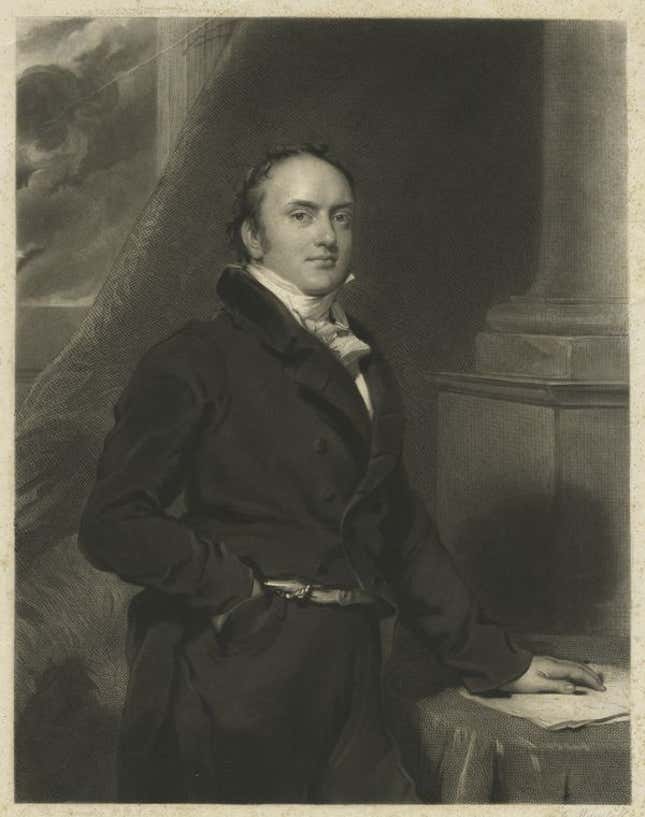

France’s fiscal comeback began with the help of one of the world’s most esteemed financiers, the British banker Alexander Baring, one of the heads of Baring Brothers & Co, as well as of the London branch of the Dutch bank, Hope & Co. Starting in 1817, Baring issued a series of loans to France. After underwriting the loan, Baring then sold the rentes, as government bonds were known, to investors via the secondary market.

At first, the yields on France’s war bonds went for 8-9%. But as more issues expanded the size of the public market, and with the confidence boost from the Baring brand, the European public grew eager to invest. The value of rentes appreciated. As Charles Kindleberger recounts in A Financial History of Western Europe, the last of these loans led by Baring Brothers, in 1818, went for 67% of the face-value price. By 1821, that issue was trading at 87%; within two years it hit 90% (implying a yield of 5.6%). That made it increasingly cheap for France to issue debt.

A boom in Europe’s money supply

The makeup of investors changed too. For the first tranche, around three-fifths were bought in France; the rest in London and Amsterdam, according to a paper (paywall) co-authored by Kim Oosterlinck, a finance professor at Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management. Eventually, around one-third of the 300 million francs worth of loans issued in 1817 wound up trading in London. (Indeed, when David Ricardo died in 1823, the eminent economist and investing whiz was holding 11.7 million francs worth of rentes, notes White.)

The sudden appearance of a huge supply of highly liquid bonds effectively “recycled” the reparation bond payments into the real economy, notes Kindleberger. With its creation of a highly liquid rentes market at home, rentes functioned increasingly like money, in that they could be exchanged and used as collateral. So even as France transferred the funds raised from rentes issues to Britain, Prussia, and other countries pay its war debts, its money supply didn’t much shrink. The Baring rentes, in some sense, financed themselves. Meanwhile, France’s war payments increased liquidity in recipient countries (offset by the bond subscriptions from those countries). The net effect was a upsurge in overall European money supply.

This instrument was an early evolutionary branch in the development of global finance. The Baring loan paid interest in francs, exposing foreign investors to the risk of loss if the franc lost value against their home currency. As a practical matter, their denomination in francs also made the rentes harder to get ahold of than domestic assets.

The next big innovation in global finance removed both the risk and the inconvenience.

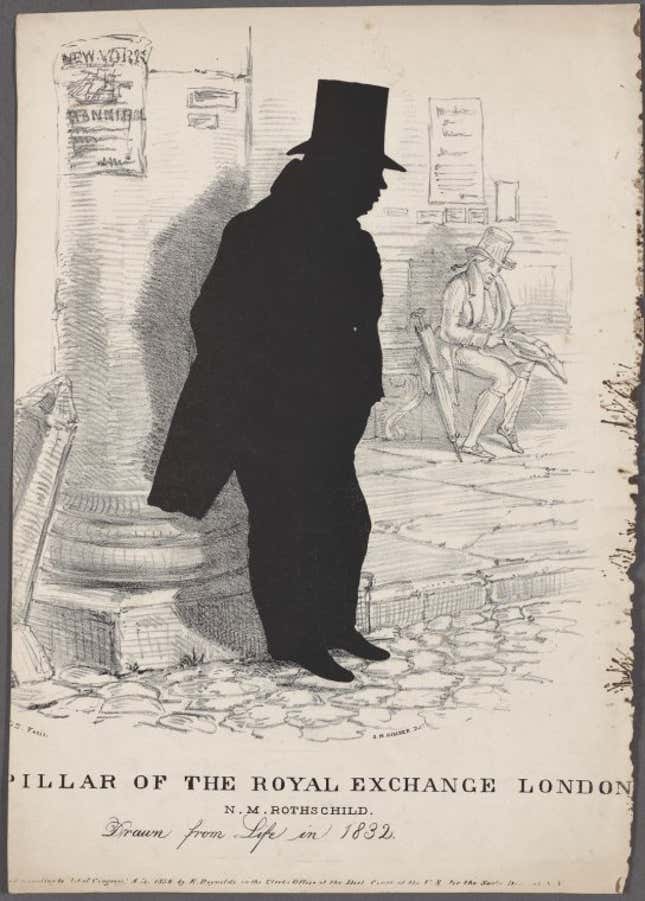

Nathan Rothschild’s finance breakthrough

Prussia knew the French indemnity payments were on the way. But with its economy still ravaged by war, it wanted the money ASAP. To tide itself over, Prussia hired the famous Rothschild bank, based in Frankfurt, to underwrite a bond issue worth 20 million Prussian thalers, as Niall Ferguson recounts in his book, The House of Rothschild.

The structure of the bond issue that Nathan Rothschild designed would forever change global finance. For one, it was denominated not in the Prussian currency of thalers, but in sterling—the dominant currency of the era. That eliminated the exchange-rate risk for British investors. The bond was issued, naturally, in London, but also in the other major finance centers of Frankfurt, Berlin, Hamburg, Amsterdam, and Vienna. Rothschild also persuaded the Prussian government to make payments to investors at any Rothschild branch—in other words, not just in London but all over Europe. That cut the cost and inconvenience to foreign investors.

“This deliberate Anglicization of a foreign loan was a new departure for the international capital market,” says Ferguson, adding that it “represented a major step towards the creation of a completely international bond market.” Within a few years, these innovations had become standard, fusing the fragments of Europe’s disparate financial markets into an increasingly globalized system.

Easy money goes global

Just as these financial innovations were deepening capital connections across Europe, British financial reform and its swelling bullion reserves kept pumping out even more new money. First came a bond refinancing by the British government, which functioned like a modern-day central bank cash injection via open-market purchase. That freed up funds for riskier investments. At the same time, the war’s end dramatically slashed military spending and revived trade, causing the Bank of England’s gold reserves to swell—expanding Britain’s money base.

In addition, British Parliament in 1822 cleared provincial banks to issue currency. The resulting surge of bank credit to British investors drove more speculation, particularly in land and other assets. And since these were used as collateral for still more credit, the process sucked even more new money into the system.

With investments in Europe pretty picked over, all this extra capital had to go somewhere. Investors didn’t need much encouragement. As with all periods of intensifying globalization, optimism ran high, buoyed by radical leaps in communication, industry, and transport technologies—for example, the first passenger railways, the rise of textile manufacturing, and the frenzy of canal building following the success of the Erie Canal in the US. Moreover, these advances opened up new corners of the world to global trade and capital.

By far the biggest darlings of European—in particular British—investors were Latin American countries, which offered much higher returns that the dreary 4% yields on British debt. Geopolitical factors were turning Brits into emerging market bulls as well. Latin America’s recently won independence from Spain promised liberal governance and the deepening of trade patterns that would preserve England’s dominance over an increasingly integrated world economy.

The Latin American debt bonanza began in 1822 with a massive loan to Colombia, which journalists and investment advisors hailed as the next US. Next came big bond issues by Chile, Peru, Mexico, Brazil, Guatemala, the city of Guadalajara, and Buenos Ayres. So heady was the Latin American debt fever, European investors bought some £200,000 worth of bonds offered by the Kingdom of Poyais, Scotland’s lone colony. Poyais bonds traded up briskly for a bit—until investors noticed that the kingdom didn’t actually exist (at least not beyond the imagination of a Scottish adventurer-cum-conman).

The global investment binge wasn’t limited to Latin America (real or imagined). Across the Atlantic like Denmark, Greece, Portugal, Naples, Austria, and Russia churned out huge sovereign debt issues too. ”What is striking about this episode, and all the ones that followed,” writes Pettis, “is how quickly risk aversion melted away during a period of easy money.” But when money started tightening, fear returned just as quickly.

Boom gives way to bust

As capital flowed out of Britain and into emerging markets, the Bank of England’s gold reserves shrank dramatically, falling from £14 million in 1824 to just £2 million by late 1825. To stem the outgoing tide and rebuild reserves, the bank hiked rates.

The sudden rise in borrowing costs first hit the British banking system. The collapse of two London banks in December 1825 set off a panic, causing even more banks to fold as depositors withdrew their money and loan recipients defaulted. According to Pettis, 76 of the 806 banks in England and Scotland collapsed. Throughout the wider British economy, demand imploded. Within months, the crisis had spread throughout Europe. As the banking system across the continent clung to money, liquidity collapsed. Thanks to new transatlantic financial connections, Europe’s tight money hit Latin America too. By 1829, every Latin American sovereign except Brazil had defaulted.

“Every loan… but seats a nation or upsets a throne”

The global impact of the post-Napoleonic war lending boom was why German philosopher Friedrich Engels, writing in the late 1870s, called the incident the “first general crisis” of international economic proportions, noting that, from then on, every decade or two, similar panics would wrack nations around the planet.

Even without the benefit of hindsight, though, it was plain that something about how money connected people had changed dramatically. Take, for instance, the unlikely source of Lord Byron’s “Don Juan,” the poet’s wildly popular satirical epic. In a section written in 1822, he opined, ”Oh gold! I still prefer thee unto paper/Which makes bank credit like a bank of vapour.” The poem, which includes some disturbingly antisemitic language, also says that every loan made by Rothschild and Baring “seats a nation or upsets a throne.”

Déjà vu all over again

Indeed, nearly two centuries later, not a lot has changed. In his review of the 1825 disaster and the dozens more that followed, Pettis draws an important distinction between two types of global financial crises.

On one hand are those that hit in the middle of a globalization cycle, when international financial centers are still in the process of whipping up liquidity. These types of financial crises can certainly be disruptive and dramatic—think the 1994 Mexican Tequila crisis and the Asian financial crisis of 1997. But they’re seldom catastrophic. Thanks to the steady global demand for big debt issues, financing strains tend to be temporary and markets recover swiftly.

Then there are those that break out at the end of a globalization cycle, exemplified on a tiny scale by the events of the 1820s. Triggered by a sudden scarcity of capital, these long-term liquidity contractions are the ones that wind up devastating local economies for years to come, crippling global growth in the process.

The current moment looks more like the latter: the twilight of an era of easy money and frenzied financial globalization. Already Argentina is already in financial shambles, with Turkey hot on its heels. Will the crisis spread from there? Maybe not: The slow-building threat of US tightening has given emerging-market leaders plenty of time to build reserves, limit reliance of dollar-denominated sovereign debt, and rein in budget deficits. But if the lessons of history are anything to go by, the deeper their ties to global financial centers, the less control smaller countries have over their own monetary systems—which means there may be more shakeups ahead.