Even in North Korea—where the government controls almost all aspects of life—markets have become an inescapable economic reality.

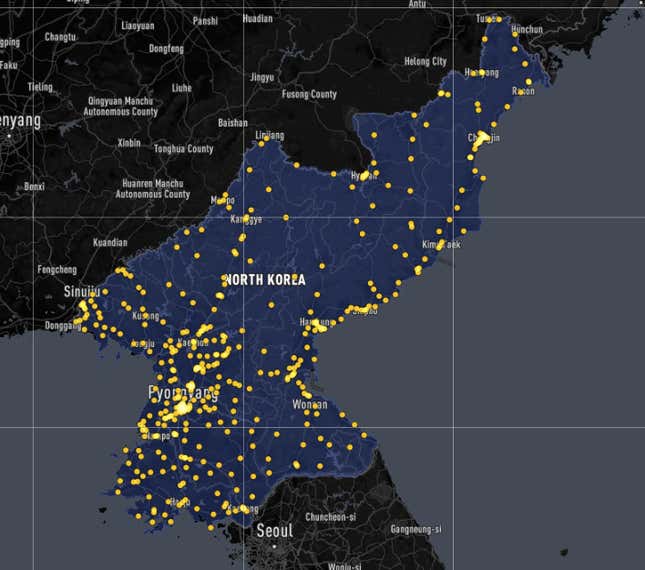

There are 436 officially sanctioned markets in North Korea, according to research released yesterday (Aug. 26) from Washington-based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), with help from Seoul-based think tank North Korea Development Institute. Together, these markets bring in about $56.8 million a year for the government through taxes and rents. The largest of them, Sunam market, in the country’s third-largest city Chongjin, makes almost $850,000 a year.

CSIS dates the rise of markets in North Korea to 2002, led by trade over the North Korea-China border. The process of marketization over the past two decades was at times a “bottom-up” initiative as everyday citizens turned to trading for survival, said the report’s authors—and at other times was encouraged by the state in order to relieve social, political, and economic pressures. Where necessary, however, the state has also cracked down on market activity, such that the marketization process has been “full of fits and starts.”

The report collected the data through satellite imagery and field interviews cross-referenced with testimonies from defectors and other secondary source materials.

According to a recent survey of 36 North Koreans conducted by the authors of the report, 72% of respondents said that almost all their household income came from markets, and 83% of people said that outside goods and information had a greater impact on their lives than decisions by the central government. CSIS said that many North Koreans they surveyed expressed anger at attempts by the government to redenominate the currency, or change the value of its banknotes, in essence destroying the cash holdings of citizens.

The growth of markets in North Korea’s economy has been particularly swift under Kim Jong Un, who, in a break from his father and grandfather, has worked hard to portray himself as an economic reformer since coming to power in 2011. Last year, the New York Times reported (paywall), citing research from the Korea Institute for National Unification in Seoul, that the number of markets in the country had doubled from 2010 to 440, while the director of South Korea’s intelligence service said that at least 40% of the population is engaged in some form of private enterprise.

The revenue generated from these markets is a particularly crucial source of income for the Kim regime at a time when international sanctions have hit the country hard. According to South Korea’s central bank, which conducts its own research on its neighbor’s economy, North Korea’s GDP contracted in 2017 after an expansion the previous year due to a fall in mining exports and industrial activity.

But Kim’s encouragement of private commercial activity could come at a cost. CSIS posited that the continuing growth of markets in North Korea could lead to the rise of a “latent civil society,” as more and more people use mobile phones to text each other (on an internal network), sharing information and developing further autonomy from the central government.