Chinese companies investing overseas aren’t telling anyone what they’re up to

Just as it was getting harder for Chinese companies to wring profits out at home, the global financial crisis made overseas assets super-cheap. That sent waves of Chinese companies investing overseas. While China’s outbound investment totaled just $9.9 billion in 2005, it hit $42 billion in the first six months of 2013 alone, according to the Heritage Institute, a think tank. And the rate of increase is now higher than that of foreign direct investment into China.

Just as it was getting harder for Chinese companies to wring profits out at home, the global financial crisis made overseas assets super-cheap. That sent waves of Chinese companies investing overseas. While China’s outbound investment totaled just $9.9 billion in 2005, it hit $42 billion in the first six months of 2013 alone, according to the Heritage Institute, a think tank. And the rate of increase is now higher than that of foreign direct investment into China.

Many are wary of this trend. While some worry Chinese multinational companies (MNCs) are proxies for the Communist Party, others think they’re prone to abusing workers and the environment in poor countries where they operate.

Those fears might be baseless, but top Chinese MNCs aren’t doing much to assuage them. Chinese companies “lag behind in every dimension,” found Transparency International, an anti-corruption organization, in its report on transparency of 100 emerging-market MNCs.

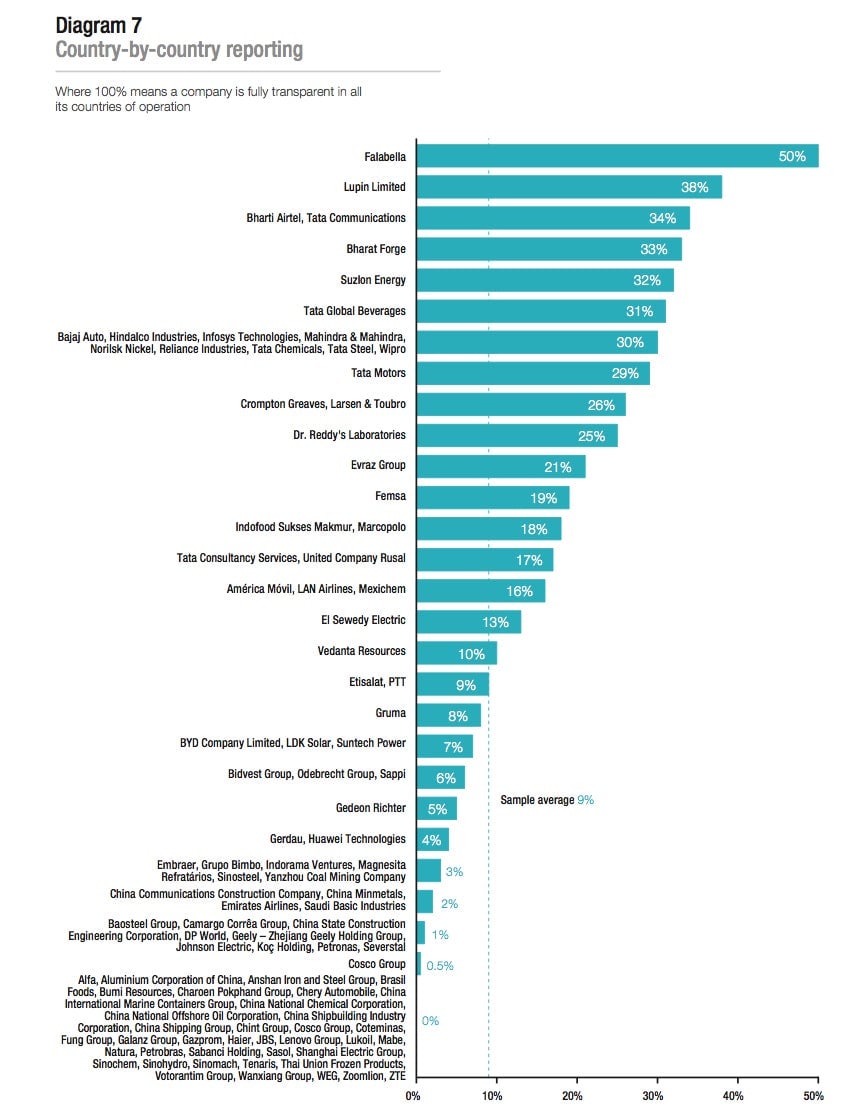

The 32 Chinese companies surveyed were especially awful at disclosing country-specific operations (including those in China.) The most open—solar companies LDK Solar and Suntech Power and BYD, a Warren Buffett-backed electric vehicle-maker—scored a mere 7% on the transparency scale. By comparison, the 20 Indian MNCs in the study averaged 29%, while Chilean retailer Falabella scored a whopping 50%. (Ratings are based on country-level disclosures of revenue, income tax, capital expenditures, community investment, and project descriptions.)

That information is important for holding companies accountable for their operations in a given country.

But embracing transparency isn’t just a sop to public interest watchdogs. By obscuring corporate governance, Chinese companies only hurt themselves. For one, this opacity helps tar them with the “Huawei and ZTE” (pdf) brush that assumes Chinese execs are doing the Party leadership’s bidding.

For example, when Haier, the world’s biggest appliance maker, opened a plant in South Carolina in 2003, some suspected an ulterior motive. ”Ultimately, the managers are accountable to the political leaders,” said Zhiwu Chen, a professor at the Yale School of Management, at the time. It’s a common suspicion, and one that tends to intensify where natural resources are concerned.

Sometimes that’s merely paranoia, though. Haier’s move seemed most plausibly geared toward boosting its high-end refrigerator business. And Erica Downs, a fellow at Brookings Institution, a think tank, argues that Chinese oil companies almost always decide where and in what to invest based on profit opportunities (pdf, p.48), and that the central government usually has at most a passive role.

The opacity of Chinese companies can be scary for shareholders, forcing them to make speculative investments instead of rewarding sound corporate governance. It’s hardly surprising that foreign institutional investors picked to invest in Chinese mainland markets have spent only 43% of their allotted quota.

There shouldn’t be anything automatically alarming about Chinese MNCs expanding overseas. The fact that there is signals how damaging the lack of transparency is for their reputations. And while it might not hurt cash-rich state-owned behemoths that dominate TI’s list, lack of transparency prevents China from deepening its capital markets, which would both spur growth and wean it off bank credit. If China want more people to invest in its markets, its companies need to start explaining why they should.