Humans are evolutionary oddballs. Unlike the vast majority of mammals on the planet, humans with ovaries can live decades after no longer being able to give birth. This means we go through menopause. Most other mammals stay fertile until the tail ends of their lives, which are also usually much shorter than ours.

There are a few other exceptions. Strangely, though we share this trait not with our closest evolutionary cousins, but with a handful of sea creatures. Scientists already knew that killer whales (also known as orcas) and short-finned pilot whales go through menopause, and now they’ve added belugas and narwhals to the list.

Researchers from the University of Exeter, the University of York, and the Center for Whale research in Washington state published these findings on Monday (Aug. 27) in Scientific Reports. They teamed up to look through published papers describing the anatomy of 16 different species of toothed whales. Specifically, they were looking at two features: the teeth, which can show age, and ovaries, which gain little markings every time a mature egg is released. By looking at age and ovulation, the researchers could put together how long female whales of different species lived after they stopped being capable of reproducing.

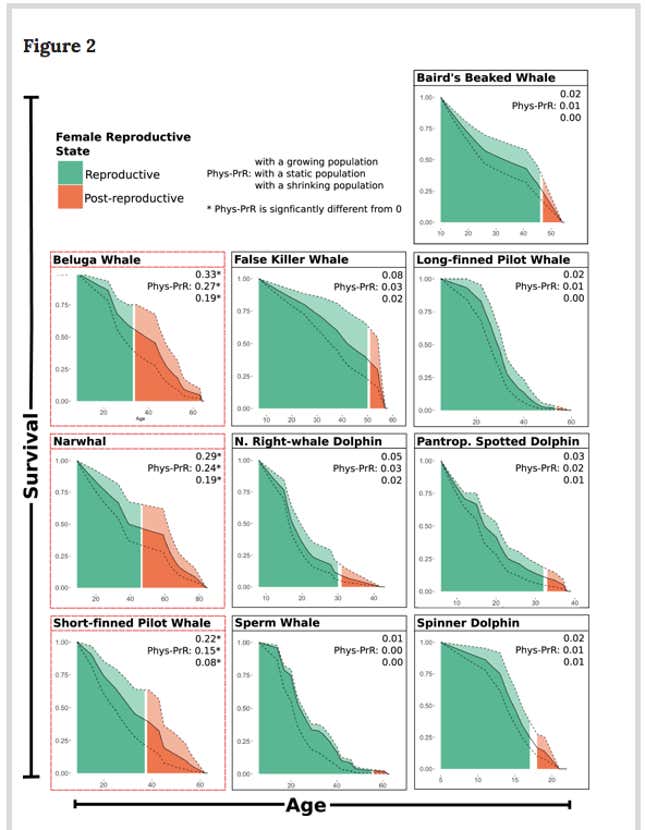

In most cases, whales appeared to be reproducing right up until they died. But—as you can see in the charts below, reproduced from the study—belugas, narwhals, and short-finned pilot whales had longer post-reproductive years than other species, indicating they likely went through menopause.

By identifying belugas and narwhals in addition to the other known species, the researchers doubled the number of mammals known to go through and live beyond menopause.

The question, of course, is why. Because this team was merely going through anatomical records rather than observing creatures in the wild, they didn’t have the sorts of behavioral data that would lead to a conclusion. But there is one theory, based on previous work on orcas: Once they stop reproducing, grandmothers stop competing with their daughters for mating opportunities. That enables them to live in and play an important role in social pods for longer.

Orcas live in matriarchal pods, where all the male and female offspring stay together. Earlier studies have pointed out that adult orca sons are more likely to survive with their mothers around. Grandmother orcas have also been spotted sharing catches of fish with their grand-calves. It appears that grandmother orcas help the pod’s survival as a whole, which ends up ensuring their DNA gets passed down.

Narwhals, belugas, and short-finned pilot whales all have different social structures, and their behavior hasn’t been well-documented enough to say whether or not grandmothers are as important as they are in orcas. But scientists do know that the ability to live beyond fertile years evolved three separate times in toothed whales—once for killer whales, once for short-finned pilot whales, and once for the shared ancestor of both belugas and narwhals. Whatever the reason for menopause in toothed whales, it seems it’s crucial for the species’ survival.

Hopefully, scientists will have the chance to figure out why this is the case. Sea creatures have always been hard to study, because they live where we cannot. Warming waters related to climate change mean that whales may not live as long, making these social patterns even harder to find.