Norway built a $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund on oil and gas revenues. Last year, however, the country’s central bank recommended that the fund divest the $35 billion worth of stocks it held in oil and gas companies like Shell, Total, BP, Chevron, and ExxonMobil. The move would make “the government’s wealth less vulnerable to a permanent drop in oil and gas prices,” the bank said.

Norway’s government, by contrast, has other ideas. Last week, a government-appointed commission dismissed the advice on divestment. “A sale of energy stocks would challenge the current investment strategy of the fund, with broad diversification of the investments and a high threshold for exclusion,” the commission said in a report. The fund’s existing investment strategy, it noted, is “simple, well founded and has served the fund well.”

So, what effect would divesting from oil companies have on the fund? Research by Jeremy Grantham, founder of Grantham, Mayo, and van Otterloo (GMO), a Boston-based fund manager that manages more than $100 billion in assets, suggests not much. “If investors take out fossil fuel companies from their portfolios, their starting assumption should not be that you have destroyed the value,” he wrote in June. “Their starting assumption should that it will have very little effect.”

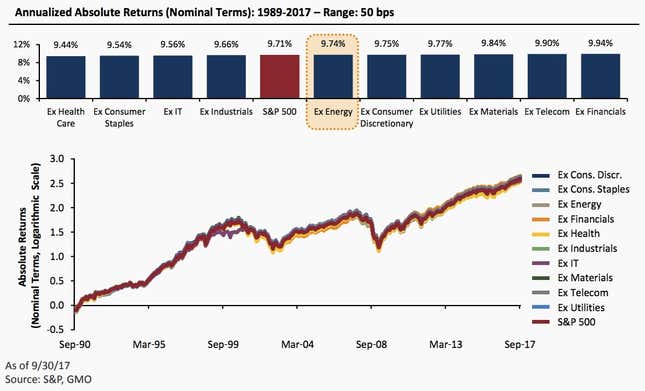

Grantham based that conclusion on an experiment. He took the performance of the S&P 500 and separated its components into 10 sectors. He then systematically removed one sector and calculated the annualized rate of return over long periods of time. Removing energy stocks meant little to overall returns over the past 20 years:

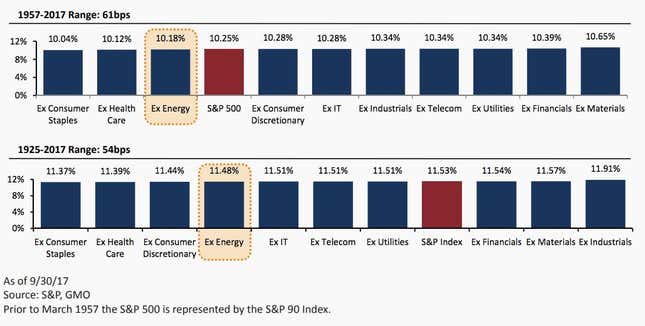

And the results hold over even longer periods, too:

Beyond not making much of a difference to long-term returns, Grantham has another argument in favor of divesting from fossil fuels. In an essay titled The Race of Our Lives, published earlier this month, he wrote: “The energy sector will be the first example of much more significant mispricing than any sector in the past due to oil companies not bending with the economic winds but fighting them all the way.”

The reason for mispricing? Climate change. “We have had a 30-year, well-funded program to make the problem of climate change seem vague, distant, and problematic, the end result of which is that we have a Republican Party wherein 60% of the people [deny climate change],” he noted. He added that Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has been making similar points about how companies underestimating the risks of climate change, which the central bank chief worries may have a catastrophic impact on markets in the future.

Norway’s finance minister says that the fund will take into consideration the conflicting advice of the central bank and the government-appointed commission before making a decision on fossil-fuel divestment this autumn.