Today’s American corporate world is a tale of two cultures. One, more traditional and common, is centralized and hierarchical. I call it “alpha.” The other, smaller and rarer, is decentralized, horizontal and inclusive. I call this one “beta.” To flourish in today’s business environment, organizations and individuals need to transition from the outdated alpha system to the fast-growing beta paradigm. At its core, beta is about, curation, collaboration and, most importantly, communication.

Alpha companies hold tight to internal secrets even when they don’t need to. In contrast, beta companies generally trust that they are staffed by grown-ups. Therefore, if an issue doesn’t involve a proprietary or competitive threat, why not engage your employees around the topic by allowing them to help brainstorm possible solutions? Why conceal information from the very people who will have to live with the results of that hidden information? Once employees confront a closed-door culture, it’s no longer about the business; it’s about the leader.

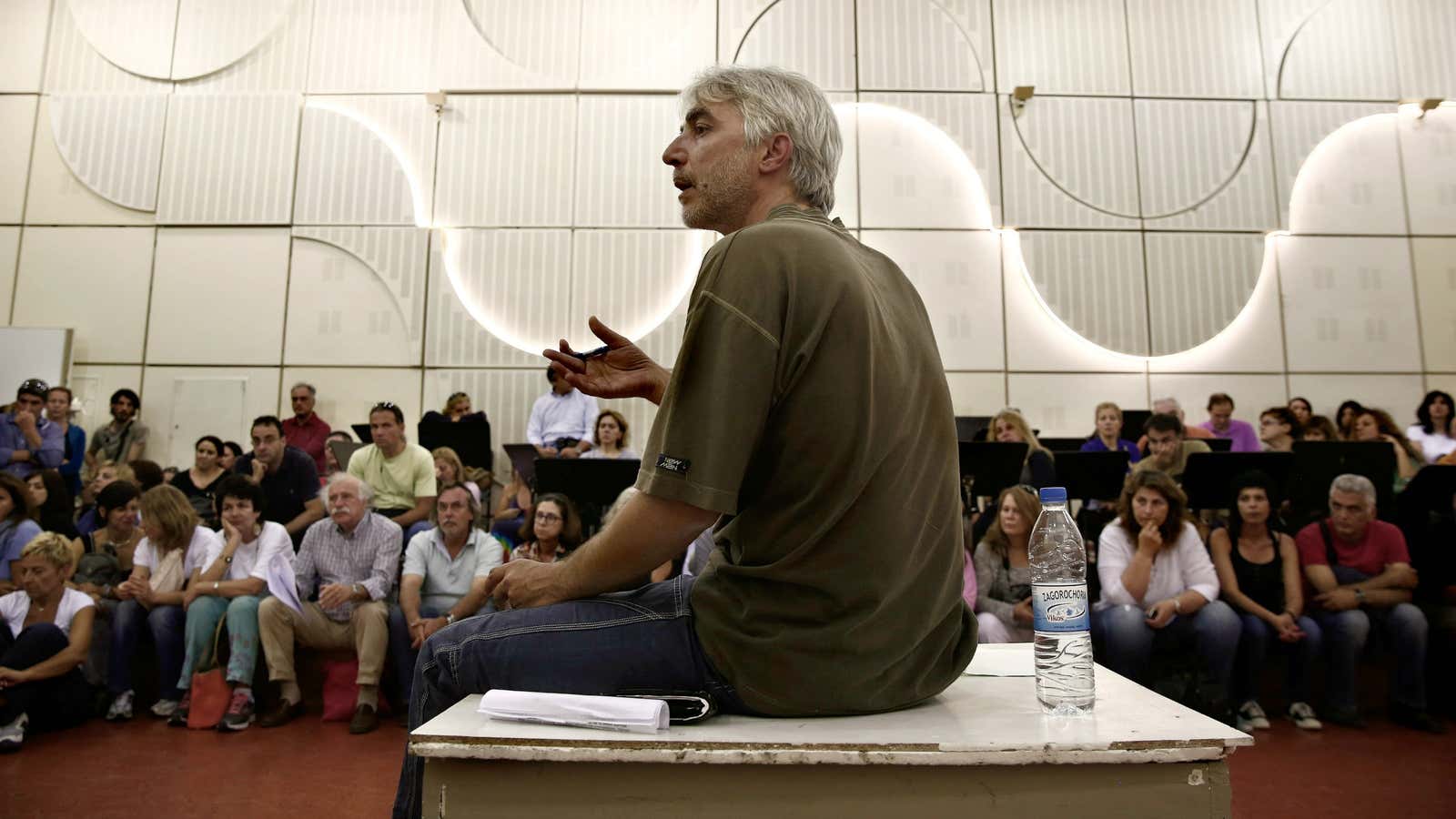

I recently coached the CEO of a large company that was in the process of being sold. Though he couldn’t divulge the names of his possible suitors, I urged him to meet regularly with employees, and to be as transparent as possible. Assembling his staff, the CEO told them he was in meetings with investment bankers, who were assessing the company’s options. To the extent that he could share information with his employees, he promised he would. First, though, he wanted to assure everyone that the company’s ability to scale was at the heart of the potential sale. “Regardless of who ends up owning us,” he said, “we are meeting with bankers because we are a leader in our industry, and in order to grow even more, and reach our potential, we need to bring in additional capital.”

After taking questions, he set up some ground rules for employee communications. Over the next few months, employees would hear a lot of internal chatter, but the company had an official policy of never commenting publicly to the media. Until further notice, he asked employees to refrain from tweeting, and even from sharing information about the company sale with family members. In conclusion, he said, “What is relevant for you to know is how highly I value all of you—and that I am selling the company because it is best for all of us, collectively.”

Again, if he had said nothing, and conducted company business behind closed doors, would his employees have known something was up? Of course. When a team of bankers shows up in an executive suite only to vanish inside a closed-door conference room, or a colleague blurts out that he caught sight of a memo featuring the names of several investment and mergers-and-acquisitions firms, it’s obvious to everyone that something is going on.

As for a company’s external communications, in many alpha organizations, the only feedback that counts is sales data and metrics. These organizations often go out of their way to evade post-transaction communications with their clients and customers. Some alpha companies shield themselves behind hard-to-navigate phone systems or bureaucracies, to the point of actually concealing contact information on their websites. Reviewers and journalists are treated with suspicion. In some consumer goods companies, information about ingredients, components and processes is kept secret from consumers, and pricing can be obscured by extra fees and hidden charges. These companies enmeshed in an Industrial Age culture seldom communicate with competitors other than via marketing challenges.

In the Information Age, this tightly controlled communication flow has to change, or organizations will be left behind. Beta companies know that communication is a resource that should be harvested constantly and used freely. They recognize that the connectivity they have with their employees, suppliers, customers and even their competitors is a prime corporate asset, which is why they facilitate and encourage communication.

“You can’t just say you care what people think,” says Gerry Lopez, the CEO and president of AMC Entertainment Inc. “You have to mean it. Younger people today demand authenticity from their leaders. They can spot if you are a bluffer very quickly. If you offer them slick explanations and try to spin them, they’ll see through it right away. The more courageous ones will call you on it. The rest will just write you off.”

This may mean you have to make the same points over and over again, says Jon Miller, investor and an executive in the digital industry. “People won’t believe you if you say something once. You have to say it a thousand times, and then follow through and actually do what you say you’re going to do. It’s only through this cumulative kind of effort that the message gets accepted. You have to be present in the company, both physically and as part of its electronic culture, so employees can see you understand things from their point of view, as well as your own.”