About 1,200 nautical miles east of Hawaii lies a patch of ocean that researchers had thought to be a desert of sorts. But for reasons unknown to them, each winter, great white sharks would leave the food-abundant waters along the US and Mexican west coast for a sojourn in the middle of nowhere.

Hoping to uncover the secret lives of the mysterious great white shark, scientists at Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California led an expedition to what’s been dubbed the White Shark Cafe. Their monthlong journey this past April and May helped them discover this area, roughly the size of Colorado, is actually teeming with “tiny light-sensitive creatures so tantalizing that the sharks cross the sea en masse to reach them,” reports the San Francisco Chronicle. The waters are also rich in squid, bigeye tuna, blue and mako sharks, and other fish.

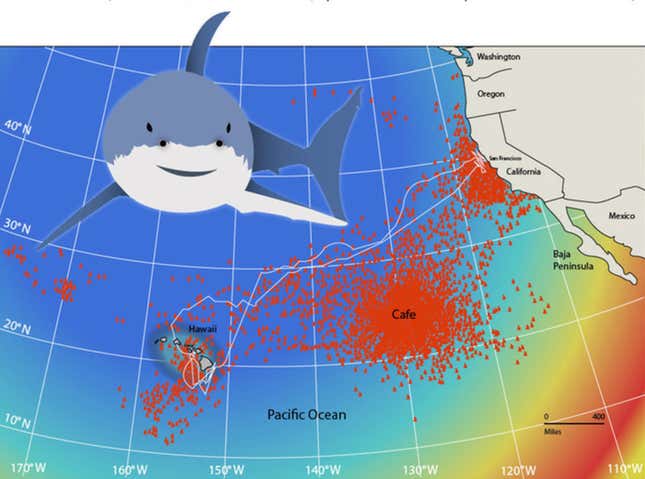

Stanford marine scientist Barbara Block had discovered the sharks’ hidden hangout, the largest known congregation of white sharks, 14 years ago after she started attaching tracking tags to the animals. Over the years, the data collected revealed that like clockwork the great white sharks would go on an annual pilgrimage in December to this area of the Pacific that satellite imagery had suggested was barren. The tracking tags helped the expedition locate the sharks this past spring and track their movements. They also revealed unusual diving behavior that isn’t entirely understood yet.

During their stay in the Pacific, the sharks kept to a surprising schedule. In the daytime, they would dive down to 1,400 feet—to an area known as the mid-water that’s on the edge of complete darkness and is populated by bioluminescent fish—and ascend to shallower waters, around 650 feet below the surface, every night.

“It’s the largest migration of animals on Earth—a vertical migration that’s timed with the light cycle,” Salvador Jorgensen, expedition leader and Monterey Bay Aquarium scientist, told the Chronicle. “During the day they go just below where there is light and at night they come up nearer the surface to warmer, more productive waters under the cover of darkness.”

While it’s believed the sharks ventured down to the darkness to hunt for larger fish drawn to the bioluminescence, researchers haven’t been able to explain another behavior they observed only in male sharks. During April, the males would each travel in a V-shape pattern as many as 140 times a day. It’s unclear if the behavior is related to mating or if they are hunting for different species of fish. Scientists hope to gain some clarity after analyzing the data they collected.