Silicon Valley is investing $19 million in space radar

The two clean-suited technicians open a door just inches wide in a small box mounted on a metal frame. They carefully unfold a metallic grey sail, spreading it impossibly across the frame to its full size, nearly 100 square feet.

The two clean-suited technicians open a door just inches wide in a small box mounted on a metal frame. They carefully unfold a metallic grey sail, spreading it impossibly across the frame to its full size, nearly 100 square feet.

“There was origami on how to fold this thing into that little box,” says Payam Banazadeh, the CEO of Capella Space, as he plays me a video of the technicians’ demonstration. He’ll show me, but won’t share it publicly, to protect his company’s “secret sauce.” Says Banazadeh, “[T]here was a lot of figuring out how to deploy it and tension it such that when it’s fully deployed, it becomes a tension antenna.”

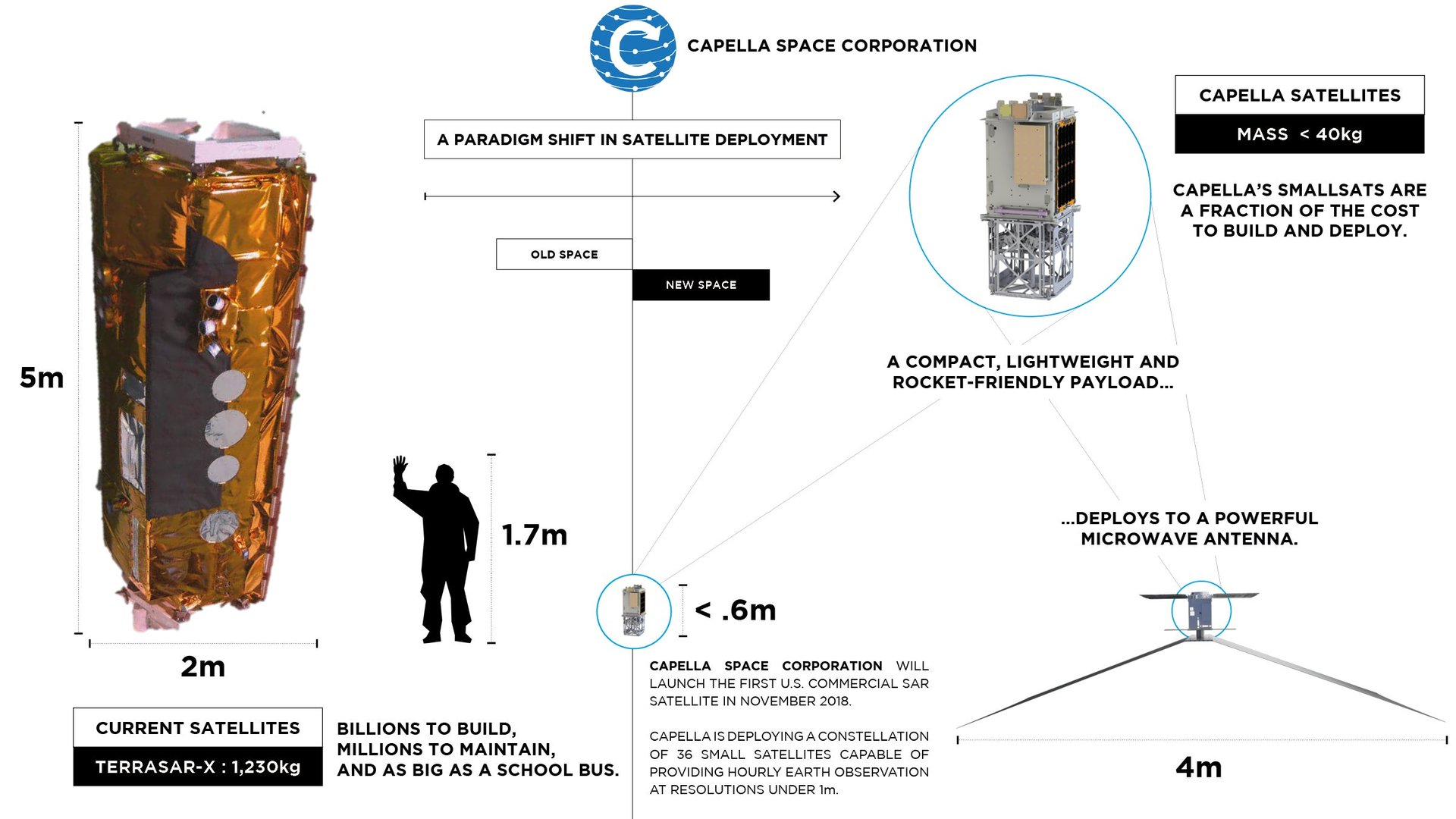

The origami practice takes place at a facility in Boulder, Colorado, but Capella is based in a corner of San Francisco’s SOMA neighborhood. It’s there that the antenna will be attached to a 36-kilogram satellite; that’s light for a satellite, and that matters in this business. The small spacecraft can be built and launched at a cost in the millions of dollars, an order of magnitude cheaper than the current generation of radar satellites.

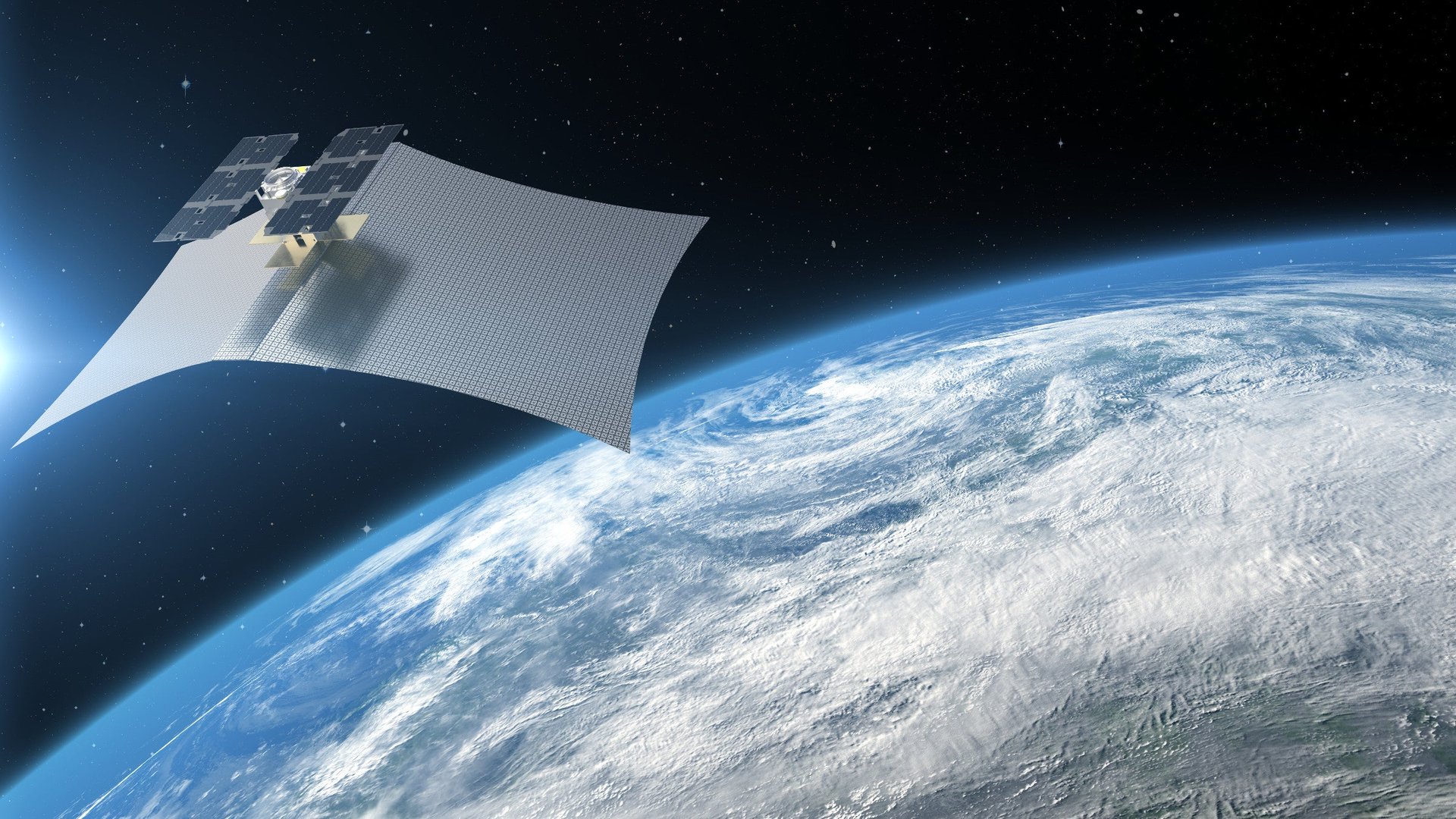

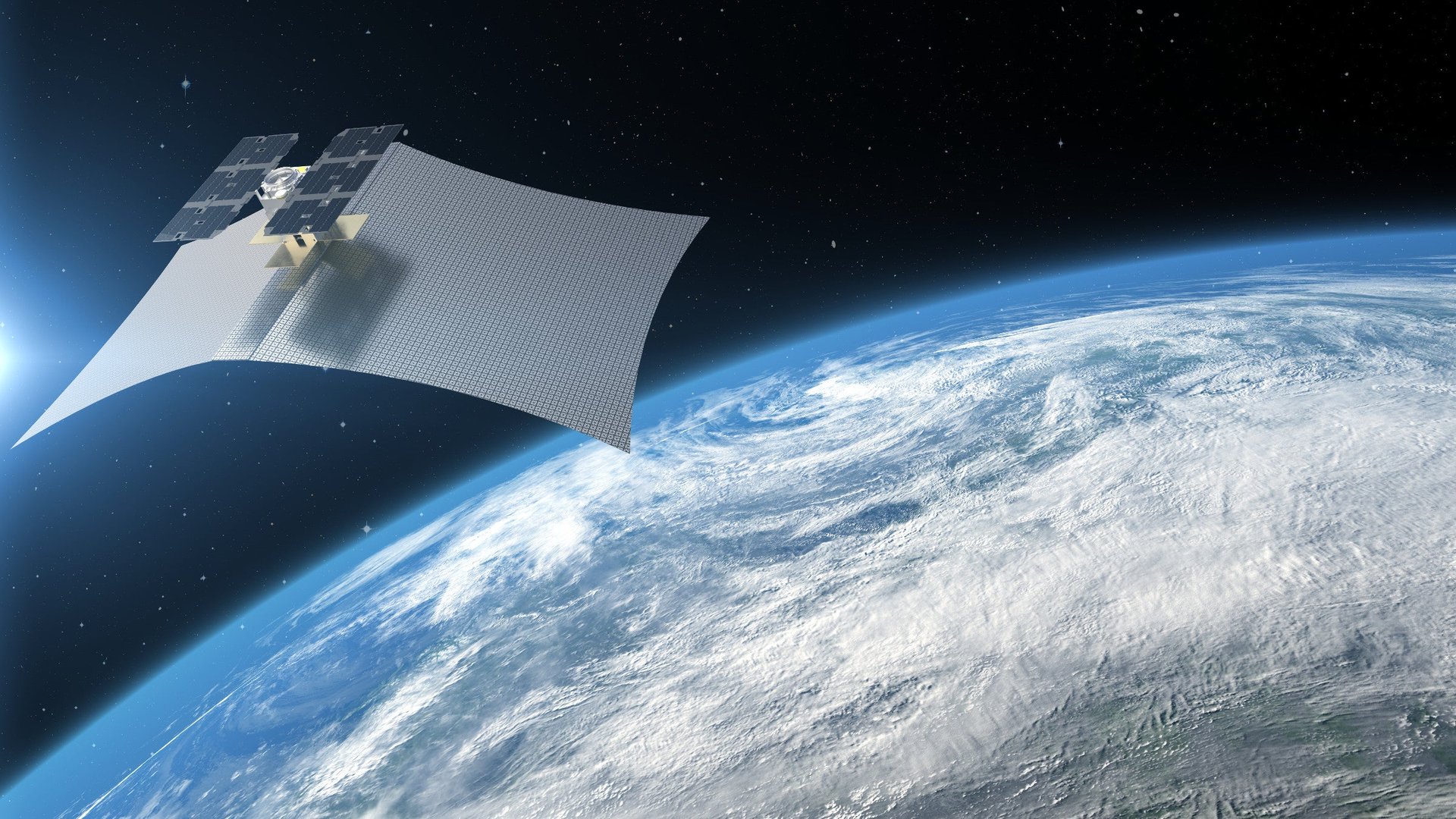

In November, it will launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Hundreds of miles above the earth, it will maneuver with a water-based thruster that Banazadeh jokes is “pretty much vaping in space.” Once in orbit, it will unfold the sail and begin bombarding the planet with radio energy. Each blast will be reflected back to the antenna, allowing onboard computers to analyze it and create a picture of the world below, peering through clouds and even under water.

This technology is called Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), and if it works, Capella will be the first US company to deploy it in space.

Space surveillance revolution

Data—especially difficult-to-get data—is everything in Silicon Valley, which is why Capella was able to raise $19 million in a series B fundraising round announced last week. Venture firms are investing billions in satellite operatorsthat are using sensors to image the Earth or building communications networks.

The round was timed ahead of the launch of the Capella’s first prototype satellite. Though Banazadeh says even the failure of the satellite can be seen as a success—”[I]t’s a success if we know why and how things went wrong”—the promise of proving that the technology works reliably is no small thing. ”Frankly, the moment the satellite gets launched and we check all the systems, then, you know, the valuation of this company is completely different,” he says.

“The money is about de-risking that antennae and proving the thesis of this company,” says Chris Boshuizen, a partner at DCVC, the firm that co-led Capella’s latest investment round with Spark Capital. Boshuizen was a co-founder and until 2015 CTO of Planet, the leading small satellite company. If the satellite succeeds, he says, Capella “can provide world coverage with SAR from a small number of very small, backpack-sized spacecraft.”

This moment was supposed to come last year. Capella’s vehicle, a ride-share Falcon 9 carrying dozens of small satellites from different companies and universities, was scheduled to fly in 2017. But the delay-plagued business of launching satellites took its toll—and with his cash “strangled” by the million-dollar deposit for the launch, Banazadeh was forced to watch a competitor, the Finnish company ICEYE, get to space first.

Radar satellites like Capella’s and ICEYE’s promise to defeat two key limits on passive imaging satellites like those flown by Planet, DigitalGlobe, or Airbus: Those satellites need sunlight and can’t see through cloud-cover. And radar satellites need enough power to transmit radio energy down to earth, requiring powerful batteries and efficient solar panels. “SAR is actual high-hanging fruit,” Boshuizen says. “The gap from passive optical sensing to active radar sensing is quite large.”

The US, Chinese, Russian, and German militaries use top-secret SAR satellites for surveillance, and civil space agencies have used them for research purposes. But private development was banned in the US until after Germany launched its first commercial radar satellite in 2007, convincing American regulators to loosen the rules.

Silver linings

In early 2018, when another waiting period appeared in the launch schedule, Capella decided to rear down and rebuild its satellite, playing a game Banazadeh calls “aerospace poker, which is, there’s a very high probability [the launch] is going to get delayed again, [but] if it doesn’t get delayed, we’re kind of screwed because we won’t have a satellite to launch.”

The team went ahead with a new iteration of the satellite and the launch was (this time fortuitously) delayed again. In the meantime, Capella more than doubled the size of its antenna, which is expected to be able to obtain imagery at a resolution of one meter per pixel—enough to spot small vehicles from space. That’s comparable to Germany’s €130 million TerraSar, which can create images with a quarter-meter resolution, and better than ICEYE’s 10 meters per pixel, though ICEYE expects to sharpen its imagery in future satellites.

Eventually, Capella hopes to launch 36 satellites in specific orbits that will allow the company to scan any spot on Earth once every hour. That criteria, along with a goal resolution of half a meter per pixel and the radar’s ability to peer through weather, are the heart of Capella’s business plan, summed up as “resolution, reliability, persistency.” For now, the company’s second satellite, scheduled to launch on an Indian PSLV rocket in June 2019, will be the first to generate revenue for the company.

One interested customer is the US Department of Defense, which lacks the ability to constantly peer at North Korea to spot the country’s mobile missile launchers. Its Defense Innovation Unit hired Capella last year to provide that data to the military. But raw imagery is just “low-hanging fruit” to Capella, which will use some of its new capital to expand its software engineering team as it looks at ways to offer data to customers who aren’t experienced users of geospatial imagery. ”The world is undersupplied with radar,” Boshuizen says.

Capella’s success also depends on a new generation of small rockets being developed by companies like Rocket Lab, Virgin Orbit, and Vector. Without affordable vehicles to carry satellites to the specific orbits needed to make the system work, putting the technology into place would simply be too costly. But the same private space revolution that made companies like SpaceX and Planet possible is now trickling down to a new generation of satellite-makers and their bespoke rockets.

“I’m surprised how quickly it happened,” Boshuizen, who left NASA to found Planet in 2010, tells Quartz. “When we were leaving NASA, our hope was Planet would be the first of one hundred space startups. We’ve well exceeded that number. We’re now at the point where people believe small spacecraft are valuable, and because of that belief, you can credibly start a small spacecraft company.”