Many space startups are vying to take the place of the world’s governments as the pre-eminent operators of imaging satellites, but this one has a unique scheme to take advantage of orbital radar.

Capella Space, which will launch its first satellite this year, aims to take advantage of a gap in current commercial satellite coverage. Most imaging satellites rely on daylight and the absence of clouds for the clearest imagery. At night or when the weather isn’t cooperating, there’s not too much to see. That big image above of the Juan Fernandez islands is beautiful, but it would be difficult to count how many boats, for example, are in the vicinity.

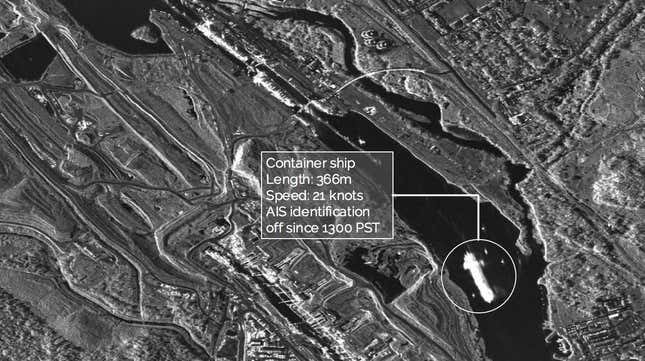

And many of the customers for satellite imagery want to be able to count those boats, or shipping containers in a foggy port, or trees underneath a mountain cloudbreak. The solution for that problem is a technology called synthetic aperture radar (SAR), which can be mounted on a satellite and used to create a 3D image of the landscape below. Here’s one such image, taken by TerraSAR, a satellite jointly operated by the German space agency and Airbus:

According to Payam Banazadeh, the founder and CEO of Capella, imagery like this will solve a key problem for consumers of satellite data, which is a lack of consistent coverage that isn’t disrupted by night or clouds. But SAR satellites are largely operated by government space and weather agencies.

Banazadeh was among the first generations of students to work on cubesats—tiny, low-cost satellites often built with off-the-shelf parts. After graduation he worked on several microsatellite projects at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Seeing the commercial potential in the technology, he sought an MBA at Stanford University. There, he met William Woods, who was finishing a PhD in remote sensing and working on the New Horizons mission to Pluto. Together, the two founded Capella to commercialize space SAR technology.

SAR satellites require larger antennae and more energy expenditure than their optical brethren because they rely on “active” imaging—rather than measuring the light reflecting from an object, Capella’s satellite will send a signal down to earth and measure how it bounces back. The “secret sauce” at the company, Banazadeh said, is in how the antennae are cleverly folded and packaged in the satellite body, and how they manage their power supply.

Since starting the company at the beginning of 2016, Capella’s founders were able to develop their technology and demonstrate it during airplane and helicopter flights. This quick development cycle allowed them to raise several million dollars from venture capitalists, including Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang, Data Collective Venture Capital, and Canaan Partners. The latter two funds have experience in the sector, with investments, respectively, in Planet, a leading satellite imaging startup, and SkyBox, a satellite imaging firm that was acquired by Google for $500 million in 2014 and is now known as Terra Bella.

Canaan general partner Deepak Kamra says a SAR satellite company is a natural next investment for his fund to “recreate our success with Skybox.” There were no fully commercial alternatives in the market, and the existing technology tended to be in the heavy and expensive satellite design paradigm (TerraSAR weighs more than a ton) rather than the light and cheap approach favored by space startups like this one.

“We think Capella has solved those problems with a cubesat, which a lot of people are surprised to hear, [but] they have some pretty unique concepts and intellectual property,” Kamra says.

To meet the expected demand for imagery, Capella expects to fly 30 satellites in total. The next step for the company, like many Silicon Valley firms with space aspirations, will be to take the data its flying sensors obtain and use machine learning and sophisticated algorithms to provide direct answers to clients. “We don’t believe our customers want to see pixels,” Banazadeh says.

For example, he says, Capella’s satellites will be able to measure changes in the ground down to the millimeter level. Oil companies already use thousands of tilt-meters placed on the ground near drilling operations to track changes that could help them improve their extraction strategies. Banazadeh says his firm will be able to deliver those measurements, from space, far more cheaply.