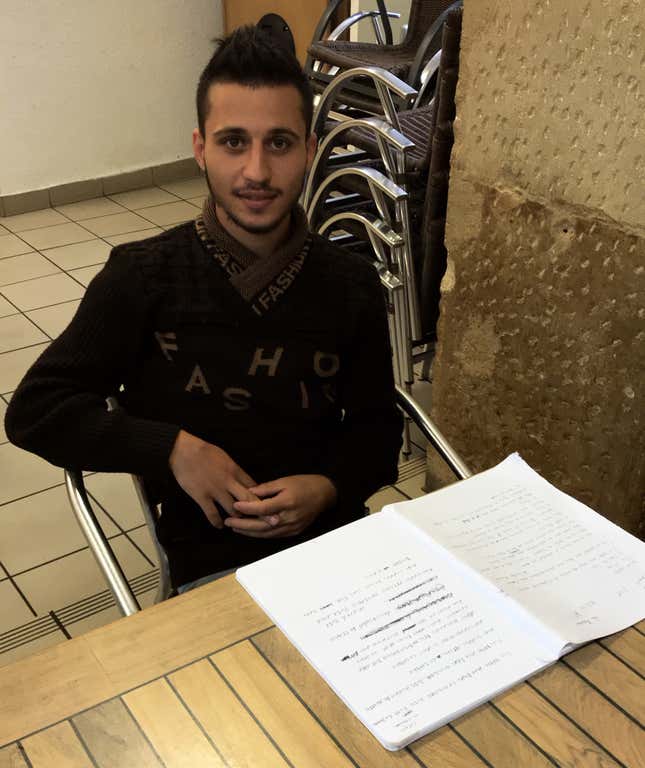

Omar and Mohammed are cousins from Damascus, and they’ve traveled a long way to get here.

The two men, both in their early 20s, fled their native Syria to avoid military conscription. They embarked upon the same journey as millions of other refugees, first arriving in Turkey and then taking a boat to the shores of Greece. But unlike many other refugees, they got lucky. They were resettled in Nancy, France, in 2017, as part of the European Union’s migrant relocation and resettlement scheme.

Today, they’re members of a volunteer civil service program, similar to that of AmeriCorps in the US, created by the French government with the goal of helping young refugees between the ages of 16 and 25 become integrated into French society. It’s a creative solution to an issue that’s plagued many European countries in recent years: In the aftermath of an unprecedented wave of refugee resettlement in Europe, what can be done to strengthen ties between refugees and their communities?

A civic way to help the most vulnerable

At the height of the refugee crisis in 2015, an estimated 42,500 people were leaving their native countries every day because of war, persecution, and oppression. That year, over 1 million migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Europe. The subsequent political backlash against refugees has brought anti-immigrant politicians to power in countries like Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, and Poland.

France is no exception. In 2017, far-right leader Marine Le Pen made it to the runoff of the presidential election partly because of her anti-immigration views (paywall). That same year, 100,755 people requested asylum or legal protection (link in French) from the French government. Of those, 31,964 were granted asylum or subsidiary protection status–21% more than in 2016 (pdf).

Many refugees in France face both social and economic isolation after arriving in their new country with little in the way of family, friends, and support systems, without speaking the language, and with no professional prospects. Not only is this kind of isolation bad for the refugees themselves, it’s bad for their broader communities, representing a missed opportunity to fold new members into local economies. In addition, studies have shown that social isolation and exclusion are risk factors for radicalization. That is made worse by the fact that refugees are often the victims of discrimination, which limits social cohesion and could make political violence more appealing to some.

In an effort to address those concerns, the administration of French president Emmanuel Macron decided to use community service as a tool to help young refugees contribute to their new country, and learn about French culture, language, and values. Today (Oct. 26), members of Macron’s administration will inaugurate the Volont’r program, a branch of the French government’s broader Service Civique initiative. The program will officially launch in January 2019.

Under Service Civique, French or European citizen between the ages of 16 and 25 can volunteer for six to 12 months for a mission that contributes to the public good in some way. The volunteers are paid a monthly stipend of €577, and given a chance to build some professional skills while giving back to their community. As of earlier this month, 300,000 people have volunteered to do the Service Civique.

Volont’r operates under a similar model, with a few twists. The goal is to recruit 1,500 young French citizens to help and support refugees, along with 500 young refugees who will receive missions that help them earn a living and learn French through government-sponsored language classes. The French citizens will help refugees set goals about what they’d like to learn and craft a plan to execute a project within their field by the end of their mission. (For example, that could involve organizing a cultural exchange program for children in a youth center, or giving regular art lessons in a senior center.)

“It will be an opportunity to … begin [the refugees’] immersion in French society, rather than stay, as they very often do in the first few months, or even the first few years, quite alone, and cut off from the environment of their new host society,” says Alain Régnier, the government’s delegate for refugee integration, who is spearheading the Volont’r program. “The idea is for them to learn the codes of French society.”

Omar and Mohammed are the first in a cohort of about 40 refugees in the Nancy area that are eligible to take part in the Volont’r program, and they say the program is already making a difference.

For the first seven months after the two cousins were resettled in Nancy, they lived in a public shelter, with nothing to do and nobody to talk to. Then the local and regional council reached out with an offer to do a Service Civique mission at a local youth center called the MJC Lillebonne. They said yes. Today, they man the front desk, participate in local activities—like the yearly soup festival or the region’s hot air balloon show—and help run sports activities for kids between the ages of six and 11. They also get weekly French classes from a local French-Syrian NGO. After finishing their 12-month mission, Omar hopes to become a mechanic, and Mohammed wants to become a cook.

Yves Colombain, the director of the MJC Lillebonne, says that Omar and Mohammed’s work in the local youth center is broadening the local community’s mind and changing the perception people have of refugees. “Bit by bit, we learn about what happened [to them], why they came here, and that obviously changes the relationship,” he explains. The staff at the center, who say they’ve already become friends with the two boys, agree.

“One of the reasons I do this job is to discover things like this,” says Haythem Kaabi, the youth coordinator at the center, “and it’s always nice to be able to exchange, to discover others, and especially when they tell us stories about what happened to them.”

The roadblocks to refugee integration

Nancy is a relatively cosmopolitan city, with a long tradition of social activism. But Colombain says that he worries about the reactions to this program from some smaller, and more close-minded, communities. “I imagine that there are municipalities where there will be debates on this. For us, in Nancy, certainly not, because we are a city that already has a strong humanist tradition … but I think there will be some towns where it will be much more sensitive.” France has a youth unemployment rate of 20%, and Colombain fears that many people will resent the fact that young refugees with no qualifications are being given employment with public funding: “People will see foreigners who come to work in France, and earn money even though there is already not enough for them.”

He says it’s been easier to promote the Volont’r program by explaining that it helps Syrian refugees, because there’s widespread recognition among French people of the horrors of the Syrian civil war. But he doesn’t expect the same level of sympathy for the other 40-some potential Volont’r refugees in the Nancy area, many of whom are not Syrian.

“The average French person understands the notion of Syrian refugees well. … I think that it is perhaps more complicated with other refugees … [who] come from countries where the political situation is less well publicized.” For those young people, Colombain says, ”there will be additional difficulties. It’s terrible to say … but it’s true.”

Régnier, the delegate for refugee integration, says that every town he has pitched the Volont’r program to has at least heard him out. And Omar and Mohammed say they’ve been welcomed by their community and haven’t experienced any discrimination. But various refugee organizations say that’s the exception, not the rule. France Terre d’Asile, an NGO that works with the Service Civique, says that discrimination against migrants and refugees in France is “commonplace.”

Régnier had the full support of the French government to develop the Volont’r program. But even he acknowledges that it can be politically sensitive–and that it has limitations. Recruiting 500 refugees into the program has been difficult because once refugees are given their legal residency permit, they often fall out of touch with government agencies, and there is no centralized way to get in touch with them. Another difficulty lies in making sure that the program serves as a springboard for refugees’ professional development—a goal that’s proven incredibly challenging, given that many refugees don’t even have a high school diploma. Colombain says he worries about Volont’r for those reasons: “I think [the program] is really good, but it’s still really small, and I don’t even dare to imagine the political difficulties that the delegate [Alain Régnier] had to face to make it happen.”

But Régnier’s ambition is for the Volont’r program to be just one tool among others for integration and assimilation. The staff of the Nancy youth center and the two young refugees themselves echoed him in saying that the program, with all its faults, is better than not doing nothing at all.

And Colombain says Volont’r can serve another purpose: To give French citizens a chance to help the victims of a conflict that they have little individual power to stop. “We are helpless, and we have the impression that even the French state, which is supposed to be a little more powerful than us … is also helpless.” He says that France’s role in Syria (which has been more involved than any other Western country) means French people have a responsibility to help the victims of this—and other—conflicts. “It’s difficult to make sense of what France has done at times, but here in Nancy, we’re trying to make up for it.”