MacArthur “genius” Sarah Stewart and the birth of a new Moon theory

The Moon is a barren rock created billions of years ago when a planet, around the size of Mars, smashed into Earth. At least that’s what the leading theory says. That collision sent bits of molten metal and rock flying, which eventually coalesced to form the Moon.

The Moon is a barren rock created billions of years ago when a planet, around the size of Mars, smashed into Earth. At least that’s what the leading theory says. That collision sent bits of molten metal and rock flying, which eventually coalesced to form the Moon.

But one thing doesn’t quite add up: the Moon’s composition is almost exactly the same as Earth’s.

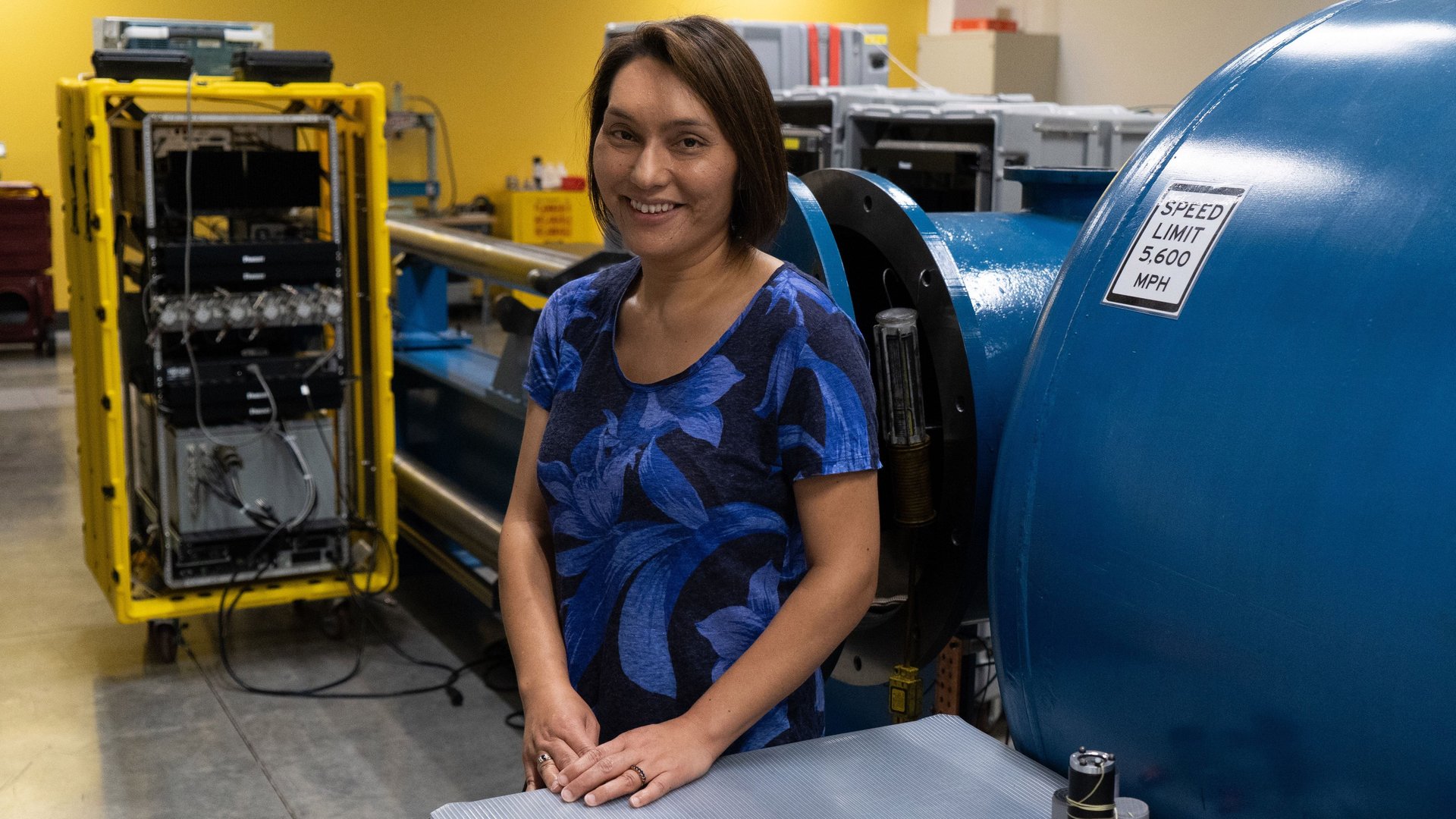

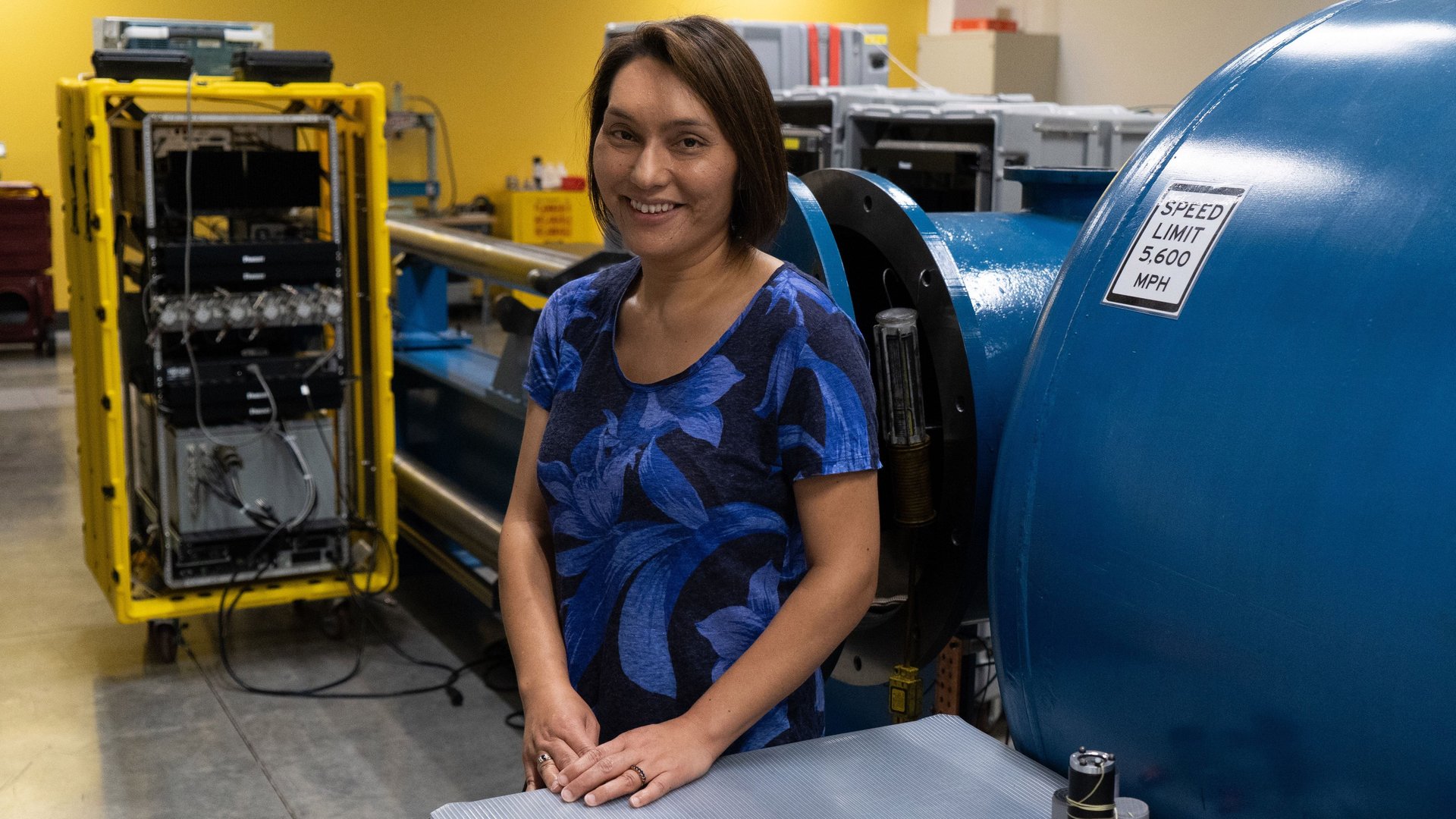

That led planetary scientist Sarah Stewart of the University of California Davis to seek out alternate explanations, and she’s landed on a new theory: the Earth birthed the Moon (paywall). This week, Stewart was awarded a MacArthur fellowship for that work.

Like the classic Moon theory, Stewart’s theory also relies on a celestial body colliding with Earth. What she sees as happening next is a bit more complex: The energy from the collision vaporized rock into a gas, and that rock vapor spun much faster than the current Earth, creating a new planetary form Stewart and her collaborator Simon Lock dubbed a synestia. Synestias were donuts of spinning, molten rock formed in the aftermath of collisions, and Stewart posits that as the Earth-spawned synestia cooled over hundreds of years, some of the spinning debris coalesced into the Moon.

To test this new theory, Stewart’s lab gets to play with cannons. By shooting rocks and minerals at one another, researchers can learn more about how celestial bodies might behave in collisions and reconstruct how our solar system was formed.

The new Moon-formation theory would explain why its composition is so similar to the Earth’s. The high temperatures—some 4,000 to 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit—at which the Moon formed vaporized certain elements while leaving others intact.

Stewart tells The Sacramento Bee that she was in shock after getting the “genius grant” call from the MacArthur Foundation. “It took a couple hours for my hands to stop shaking,” she said.