For all intents and purposes, the US has kicked its credit card addiction. At least for now.

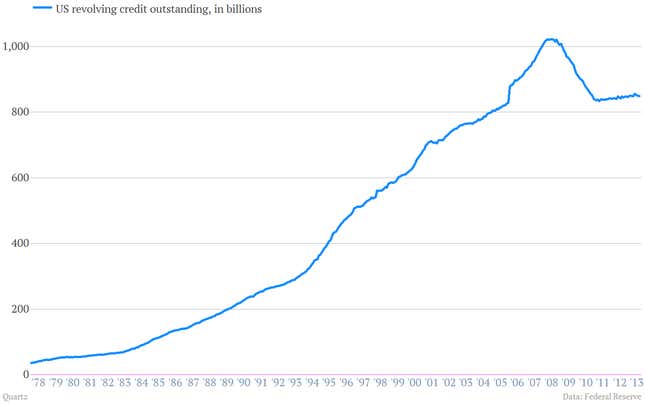

Check it out. Revolving credit, which the government first started tracking in 1968, was going gangbusters for decades, driven by credit card debt. After the crisis, it’s nearly dead in the water.

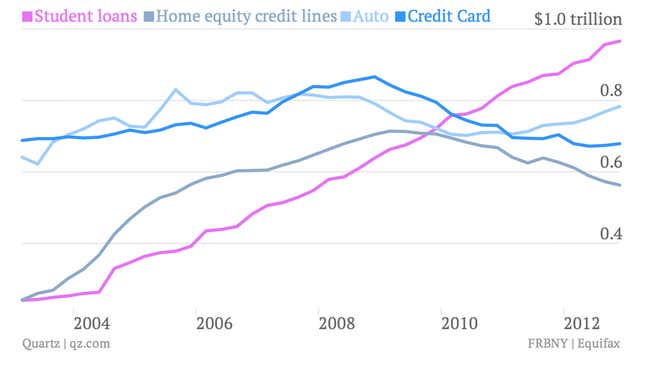

Now, yes, those numbers encompass more than just credit cards. But a separate report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York drills deeper into the data, producing quarterly numbers on credit card debt alone. The trend is the same.

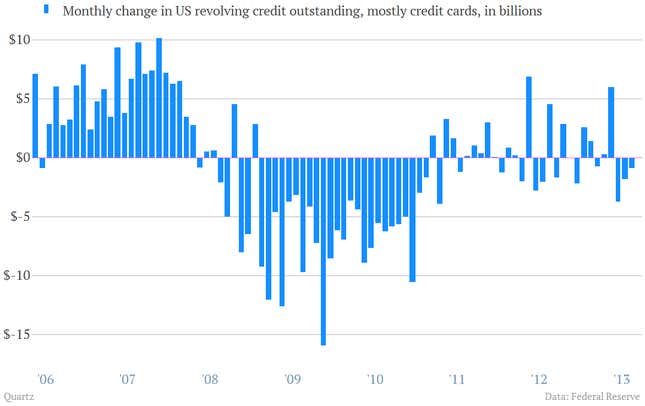

And here’s a look at how the solid monthly growth in credit card debt we saw in the years before the crisis has melted away more recently.

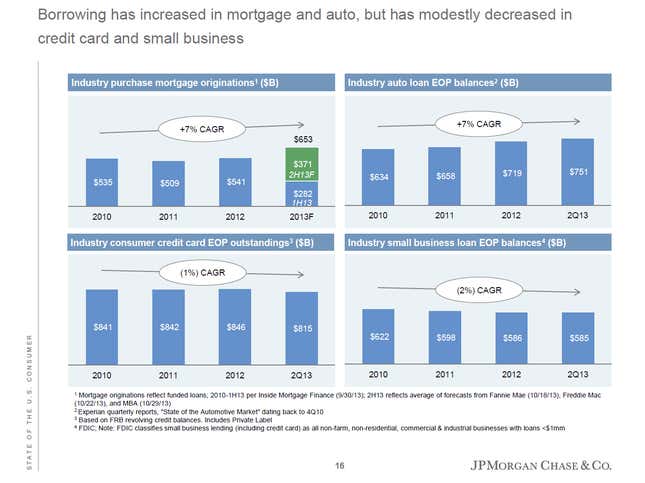

Now it’s important to note that it’s not as if Americans have completely disavowed debt. Savings rates remain laughably low when compared to some other large advanced economies. And Americans haven’t hesitated to take on other forms of debt in recent years. For instance student borrowing has continued to ratchet higher. And Americans aren’t shy about borrowing to buy cars.

But big financial companies are seeing the same thing: credit card debt growth is nearly nonexistent. Check out this slide from a recent J.P. Morgan Chase presentation on the “state of the US consumer.”

So what’s going on here? Well, for one thing, sound public policy.

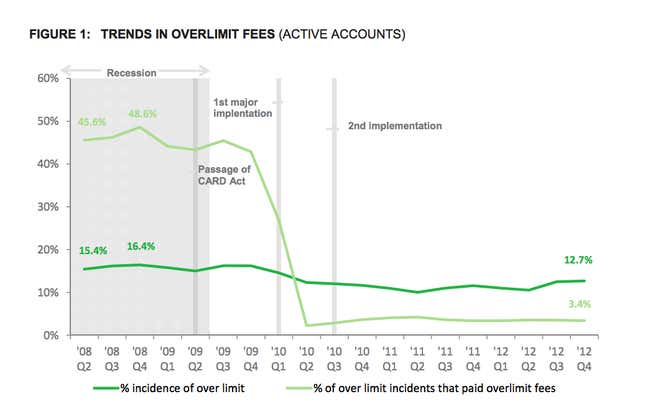

The passage of the US Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility and Disclosure Act—the CARD Act—in 2009 and its 2010 implementation completely reshaped the American credit card industry. Here’s some of what the CARD Act did:

- Blocked credit card companies from extending credit without assessing the customer’s ability to pay

- Implemented rules on marketing to people under the age of 21 to crack down abuses at college campuses

- Limited a credit card company’s ability to levy penalty fees

- Restricted the circumstances in which the company could jack up interest rates

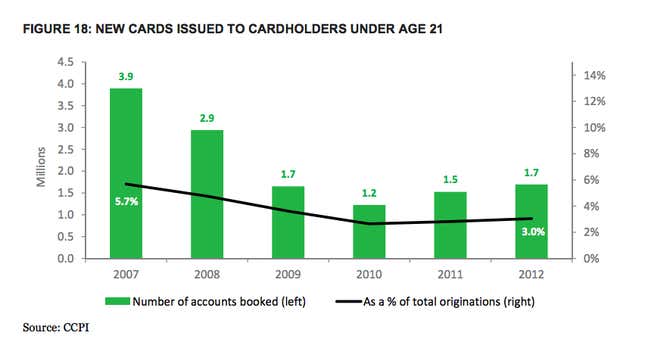

And the CARD act is working. For one thing, the industry is opening far fewer accounts for people under the age of 21. In 2007 3.9 million accounts were opened for those under the age of 21. That number was 1.7 million in 2012, down 56.4%.

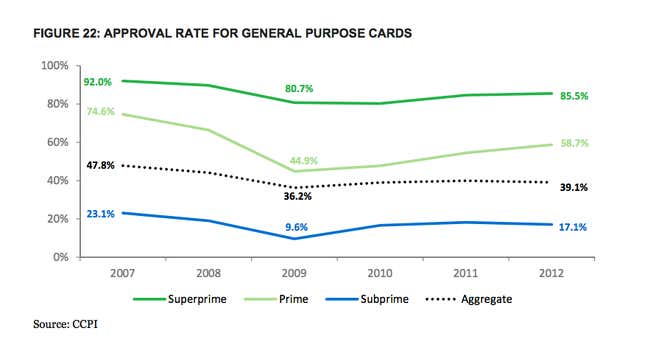

Credit card issuers are also getting much choosier about providing credit to the riskiest borrowers. You can see that approval rates for subprime borrowers have slumped since the crisis, and they haven’t bounced back as fast as approvals for prime borrowers.

“They just stopped giving cards to people who were kind of on the bubble,” said Christopher Donat, an equity analyst covering credit card companies for investment bank Sandler O’Neill in New York.

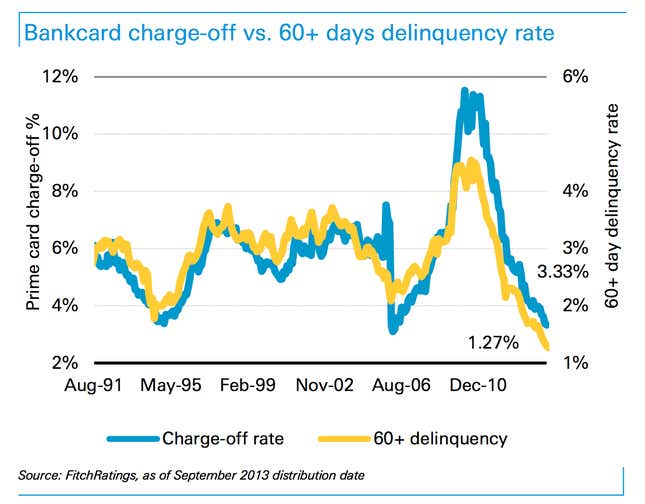

And as riskier borrowers are getting more limited access to credit, consumers with credit cards have gotten incredibly conscientious about paying on time. Delinquencies and charge-offs—credit card debt that has to be written off as a loss—have fallen to some of the lowest levels on record.

“The market has changed. It’s become smarter and it’s also following the lead of the subprime market and the mortgage market,” said Elen Callahan, a Deutsche Bank analyst covering the market for securitized credit card debt. “It’s not necessarily a great thing to give everybody credit.”

Meanwhile, consumers are also getting dinged with fewer fees.

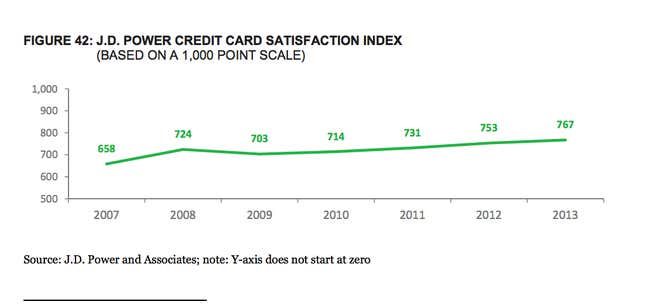

And people seem to be happier with their credit card companies.

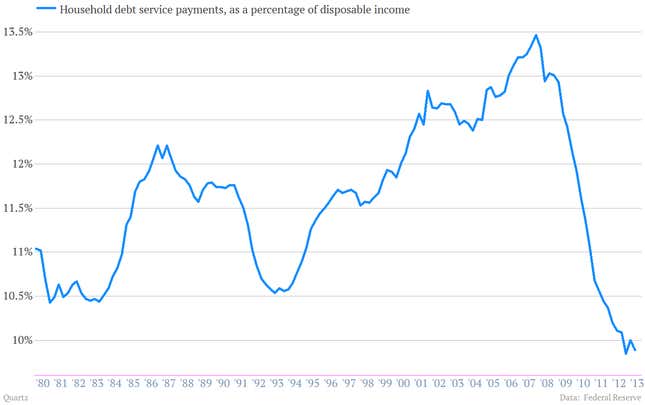

This is all part of a broad base improvement in the financial health of American households. The decline in credit card debt—along with defaults and paydowns of old borrowing—have also helped American get their finances in the best shape in years.

So are there any downsides to this development? Well, there are some people who have been denied credit, because their incomes are too low to be qualified for a card under the Card Act rules. And for some retailers, more stringent rules on signing up credit card customers have acted as a kind of headwind.

“On the consumer side, as you know, the ability to pay or the CARD Act really negatively impacted approvals,” Home Depot CFO Carol B. Tomé (May 21, 2013)

So why does this matter? Well, for one thing, and surfeit of US credit card debt has caused a lot of suffering. According to University of San Diego economics professor Michelle J. White the surge in credit card debt since the early 1980s is “the main explanation” for the fact that US personal bankruptcy filings jumped five-fold between 1980 and 2004.

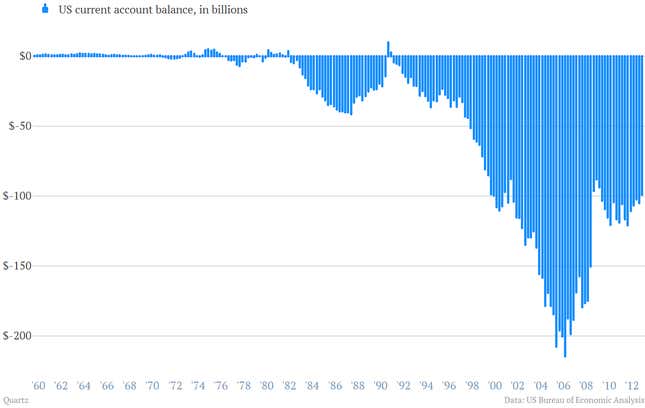

On the macroeconomic front, it’s worth noting that, for decades, US consumers have been buying way more than US producers have been selling to the world. That has resulted in a persistently large current account deficit.

The ironclad rule of macroeconomics is that if you run a giant balance of payments deficit like this, you have to borrow money from abroad to finance all that consumption. In other words, the giant US current account deficit is the flip side of the giant US national debt. If we ever get serious about getting our debt under control, that will likely mean a rebalancing away from over-consumption towards more production.

This has to be done gently. (A sharp pullback in domestic consumption would sink the economy and result in an even more unwieldy debt load.) But clamping down on credit card debt is a good place to start cutting consumption. And if that means keeping credit card companies from tricking college students into signing up for credit cards they don’t fully understand, well, good.