This post has been corrected.

Brazil and China can’t seem to agree on what either country is getting out of their economic ties. Take this most recent example: China Construction Bank, a huge state-owned lender, just sunk around $716 million into a 72% stake in Brazil’s Banco Industrial e Comercial, a nearly 19% premium (paywall) on BicBanco’s current share price. Some might argue that the move positions CCB to profit from Chinese investment in Brazil. But to hear the head of another Chinese bank tell it, that might be a naive move.

“The ardor for investment in Brazil is fading. Operating in Brazil is a huge challenge,” Zhang Dongxiang, CEO of Bank of China’s Brazil unit, told Reuters. “Public opinion sometimes seems to be against foreign investment… as if it makes local industry less competitive.”

Zhang blames his wariness about investment in Brazil on the protectionist policies of the country’s president, Dilma Rousseff. In an effort to boost dwindling government coffers, Rousseff has enacted policies such as taxing foreign-made cars and limiting the land available for purchase by foreigners.

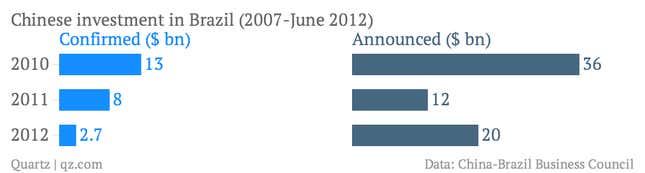

Others companies, like Huawei, are exiting due to Brazil’s slowing growth. Some two-thirds of Chinese investments in Brazil since 2007–about $70 billion in projects–have either been suspended or have been canceled, reports Reuters.

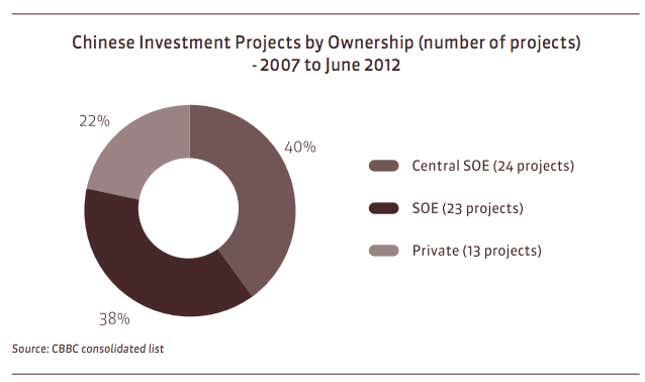

Brazilians, however, generally hold a different view. Local businesses complain that Chinese companies drag their feet on deals and are excruciatingly patient negotiators, reports Reuters–or simply never round up the funding. Many of the projects China has made good on involve Brazil’s coveted commodities. Starting in 2010, big state-owned enterprises (SOEs) like Sinopec and Sinochem have amassed plum natural resource projects.

The friction is building. The Chinese acquisition (in a consortium with two European oil companies) of Brazil’s biggest oilfield sparked violent demonstrations in Rio de Janeiro at the end of October.

It’s a similar problem to what China has faced from investing in sub-Saharan Africa, says Derek Scissors of the American Enterprise Institute, a think tank. “What happens is you start getting people saying ‘Wait a minute, we are running a huge trade deficit with China. They are investing $20 billion and grabbing up all our resources. Are we a colony?'” Scissors told Reuters.

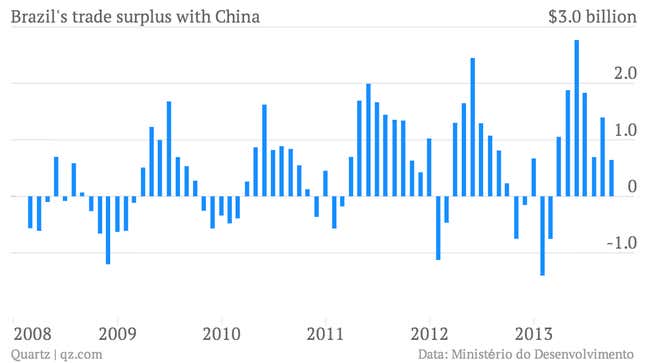

Some of the outrage probably stems from the fact that Chinese investment hasn’t resulted in deeper trade ties that boost Brazilian manufacturing, as Brazilians had hoped.

On first glance, it might appear that Brazil is ahead, since the country runs a trade surplus with China. But some 80% of Brazil’s China exports still come from three commodities: iron ore, oil and soy. China, meanwhile, has expanded the range of products and services it exports to Brazil. Lack of growth for Brazilian manufacturers is hurting their competitiveness; one study shows they’ve lost share to Chinese ones (pdf, p.19) in other markets.

Despite the bellyaching on both sides, Chinese investment in Brazil looks set to continue. China’s state-owned enterprise may be losing interest, but nimbler private Chinese companies are still seizing opportunities. Search engine Baidu recently launched in Brazil, months after Lenovo bought a Brazilian electronics company for $146.5 million. And more Chinese car brands sell in Brazil than do American or Japanese brands.

That’s a good thing for both countries, since those companies see value in Brazil beyond its natural resources.

Correction: November 2, 2013, 10:30a.m. (EST): An earlier version of this post contained a typo that put CCB’s investment at $716 billion, not $716 million.