Dennis Hof was a man of many contradictions, but he was always himself.

Shortly after I first interviewed him, Hof mailed me his autobiography, The Art of the Pimp. He wrote in it, “There is no business, like Ho business.”

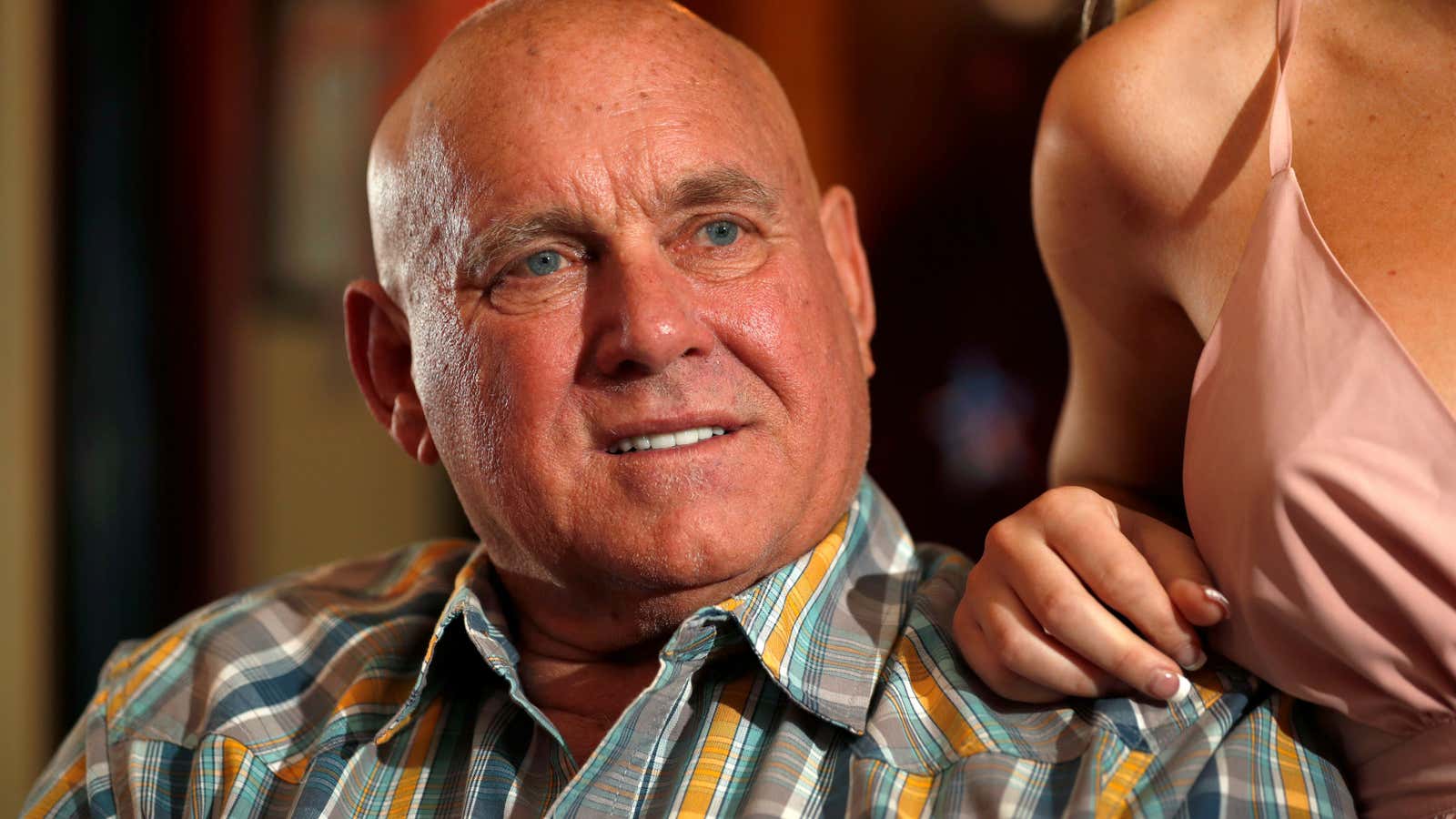

The book was a perfect representation of all his contradictions. It described his life and how he built a brothel business. By the time he died, on Tuesday (Oct. 16) at the age of 72, Hof owned seven brothels, making him the largest single owner in Nevada, and by far the most flamboyant.

In the book, Hof’s life story is interspersed with testimonials from friends and colleagues about how great he is. But towards the end, there is one from Cami Parker, a former sex worker at Hof brothels and a one-time girlfriend. She accuses him of manipulation and emotional abuse. The book ends with a psychologist, Sheena Hankin, calling him a narcissist.

When I met Hof at the Bunny Ranch, his brothel made famous in the HBO series Cathouse, I asked why he included this is an otherwise flattering biography. He shrugged and said, “all points of view should be out there.”

Hof, a self-declared pimp, leaves behind a complicated legacy. Sex work makes many of us uneasy, especially when a man profits from the work of women doing it. Hof also had sexual relationships with many of the women who worked for him.

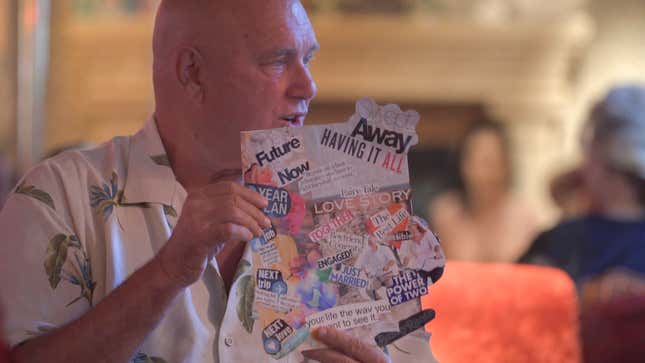

But in the time I spent covering Hof’s brothels, I could not deny the value of legal brothels. They not only provide a safe, protected venue for sex work, but Hof also offered extensive training in negotiation, marketing, and financial literacy. He encouraged all the women to set life goals beyond the brothel—during one of my visits, the women were asked to make vision boards and present them at the staff meeting. He says this motivated them to work harder, adding:

I tell the girls. it is not a good job but it is an great opportunity. You can work 5 years, work hard, save and use the financial advisors, and you’ll never have to work again… Some will never earn more than they are here, and may only be last a few years, they should use the money and skills to go on to something better.

Every woman I met in the brothel was there for a different reason, and they came from a wide variety of backgrounds. Many did not grow up with much privilege: they lived in families where men don’t work, no one has a bank account (let alone any savings), and they weren’t regularly told they could achieve their dreams if they set a goal and worked hard towards it.

When Hof bought he Bunny Ranch in the early 1990s, Nevada brothels would not let the women leave for days at a time. They had to do whatever the customer wanted, for the price the house set. Hof took his experience selling time-share property and employed a similar model to sex work. He had all the women work as independent contractors who set the terms of their own transactions, including the price, and then took 50%.

Nevada’s brothels are tightly regulated. Women must undergo regular disease screenings and risk getting fired for not using a condom. There are security guards and panic buttons in all the rooms. Sex work will happen no matter what, so brothels like Hof’s at least offer a safe venue for it. He was passionate about fighting human trafficking, and he believed legal regulated brothels are the only way to monitor transactions and prevent trafficking.

This November, Nevadans will vote in a referendum that threatens the future of legal sex work in some counties. Without Hof, the most visible champion of the industry—and a Republican candidate for a state assembly seat—it is not clear what lies ahead for legal brothels in the state.

I visited Hof’s brothels on three separate occasions. Hof was very hospitable, but I never felt totally comfortable. There was one thing about the brothels I enjoyed, however: I’d never been in any other environment that felt so devoid of hypocrisy. This is how Hof lived his life.