Hearts emanate from Jennifer Kahl’s profile picture on Twitter. She appears to be a woman in her late teens. But look at the tweets below, and you might become suspicious.

She’s tweeted 83,000 times since she joined the site a year and a half ago, which averages out to over 150 times a day. Some days she tweets over a hundred times an hour. Most days she tweets consistently through the night without taking a break for sleep.

Her tweets contain some similar themes: She promotes #Syria, trolls #zionists, and capitalizes words at random.

Kahl’s account shows some of the tell-tale signs of automation—posting at an incredibly high volume, engaging with every mention of certain words, and reposting others’ content as her own.

Researchers have found that as many as 15% of Twitter accounts are bots, which drive two-thirds of the links on the site. But not all bots are bad. There are bots that make the internet more beautiful, more useful, even kinder. Here at Quartz, we have a whole department dedicated to making informative newsbots. The issue is not that automated accounts exist; it’s that they can be—and have been—weaponized.

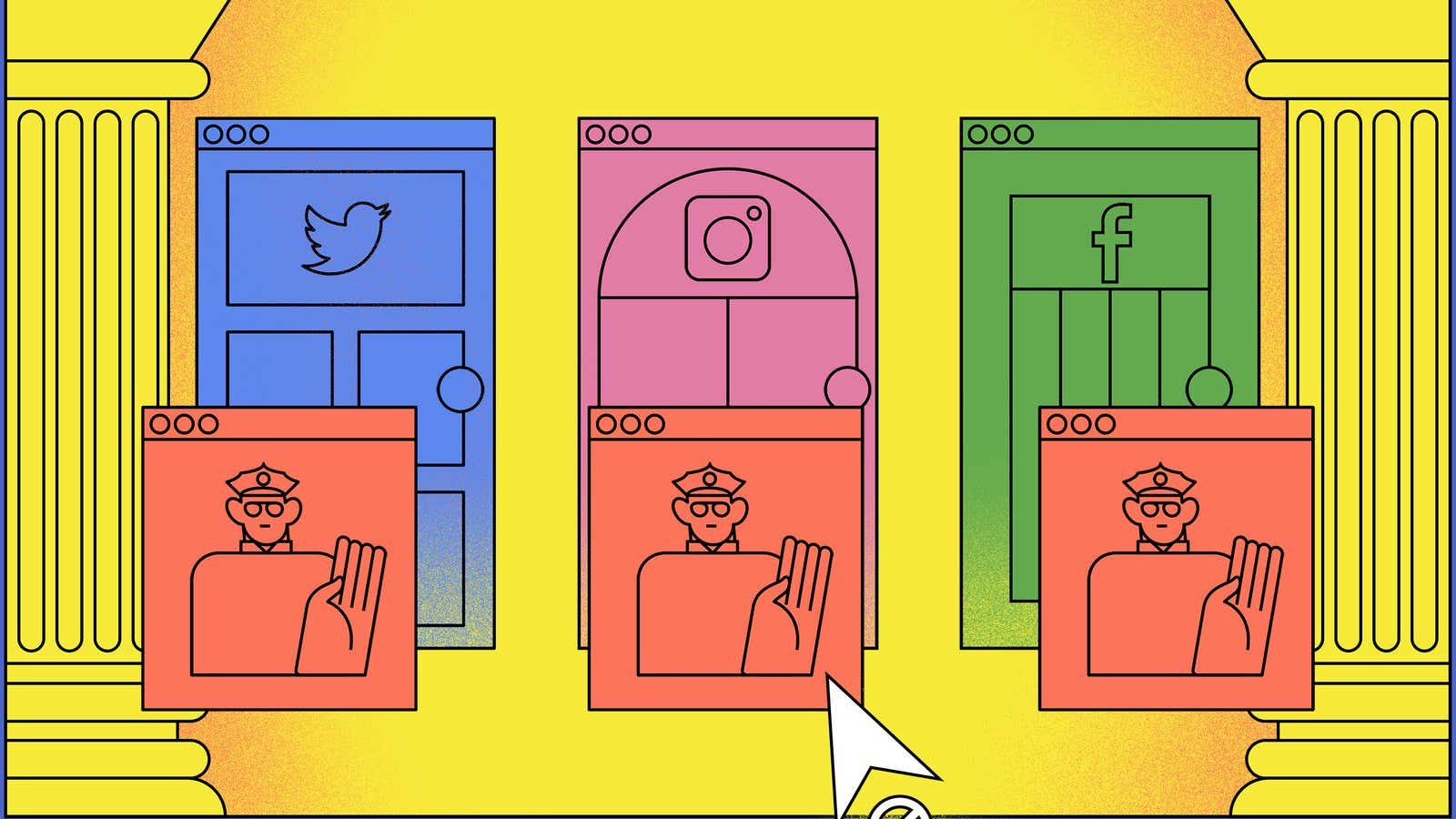

“In the run-up to the 2018 midterms, bots were used to disenfranchise voters, harass activists, and attack journalists,” says Sam Woolley, the director of the digital lab at the Institute for the Future. “But at a fundamental level, Facebook and Twitter are dis-incentivized from doing anything about it.”

The problem with social media always comes back to business models. Platforms have never had an incentive to punish accounts that worsen the experience for so many of their users; it’s just that—until recently—they didn’t have a strong enough incentive to eradicate the bad behavior either.

To understand why, let’s follow the money.

Start with the solution

When social media companies are compelled to act, they have the resources to move quickly.

The key to swift, comprehensive action is to align change with business objectives. “The business model always drives the product decisions,” says Renee DiResta, a disinformation researcher and fellow with the Mozilla Foundation. “Until it became a liability from a PR standpoint, there was no effort whatsoever [from Twitter] to think about the bot problem.”

This past spring, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey finally admitted there was a problem, a significant shift in how his company talked about automation in the past. Coming out of the 2016 US presidential election, where the social network was the canvas for a number of election-meddling, harassment, bot, and scam-related scandals, Dorsey declared “platform health” to be Twitter’s number one priority moving forward in a March tweetstorm. He made a request for proposals from experts to “help identify how we measure the health of Twitter,” and wrote “we aren’t proud of how people have taken advantage of our service.”

Since then, the company has more than doubled the rate at which it eradicates bots from its platform. In May and June alone the site suspended over 70 million fake and suspicious accounts. But wiping out bad actors from Twitter was never a matter of resources. It was a matter of priorities.

The real question is what took so long?

Monetization meets automation

On the internet, one metric rules all.

For the majority of online games, social networks, or mobile apps, maximizing monthly active users (MAUs) is the motivation behind nearly every product decision. It’s the first number executives like Mark Zuckerberg cite in quarterly earnings calls. It’s the first number aspiring entrepreneurs highlight in their pitch decks to venture capitalists. And it’s perhaps the best explanation for why bots like Jennifer Kahl are so pervasive online.

You can thank advertising.

MAUs are such a big deal because the web—by and large— is monetized through advertising. In 2018, $277 billion will be spent on digital advertising, nearly two-thirds of which is controlled by Facebook and Google. More MAUs mean more eyeballs to sell to brands. Thus, most internet platforms make signing up for an account trivial—even if the account isn’t linked to an actual human.

“Bots get added to the general count of users in general growth reports that are reported to shareholders,” says Woolley. “So, if you’re Twitter and you start removing all the bots from a platform, you’re potentially going to lose up to 20% of your user base, which is damaging to share prices.”

Kris Shaffer, a disinformation researcher at the cybersecurity firm New Knowledge, adds that MAUs perversely affect what content algorithms favor online. “The problem [with social media] is a whole lot bigger than automated accounts,” he says. “The advertising-based pay-per-click funding model is the fundamental problem. If we didn’t have the attention economy with user engagement as the proxy currency, it would really change the dynamic of what we see online.”

Although social media companies want to increase their user count and maximize engagement, there are others forces that might compel them to clean up their platforms. Advertisers, who ultimately hold the dollars that fund the services, have also been more vocal about their issues with automation on social media. After all, brands are paying for eyeballs, and bots don’t have them.

Turned tables

When Dorsey made his announcement about platform health in March, the subtext was clear: dealing with fake accounts is going to cost Twitter time and resources. Fighting spam and malicious automation will require leveling with investors about how removing bots might impact the site’s bottom line.

The problem with automation on social media has never just been about impersonation or the spread of misinformation. It’s a problem of accountability. Fake accounts exist in a system where the social media companies didn’t have a strong enough economic incentive to do anything about them.

Now the incentives have switched, and platforms are scrambling to clean up the mess. A ban of all bots would throw the baby out with the bathwater. Bots that, say, mine Twitter for haikus or tweet out words when they appear in the New York Times for the first time harness a unique kind of collective creativity that make the internet what it is. But platforms can no longer deal with malicious automation passively.

A line must be drawn on what automated behavior will be tolerated. Similar to email spam, bots pose an ongoing risk that will need to be managed. Bots were once an asset that helped prop up Twitter’s user count, but now they’re a liability. Though users paid the price initially, prioritizing growth over health created a debt that the company will have to pay off for years to come.