Typhoon Haiyan made landfall in the Philippines this morning, lashing the country’s central islands with gusts of up to 235 mph (378 kph). The storm is expected to impose $14 billion in losses on the Philippines’ economy, less than $2 billion of which is insured, reports Bloomberg.

One of the most at-risk sectors is the country’s $1.6 billion sugarcane industry. Sugarcane is the country’s fourth-largest crop, after coconut, corn and rice. And of the country’s agricultural, forestry and fishing businesses, 16.4% of them farm sugarcane, the sector with the second-most businesses after hog-farming.

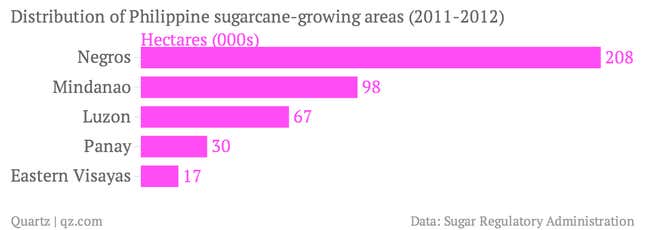

Haiyan is at the moment tearing through the Philippines’ biggest sugarcane growing islands, including Negros and Visayas. About half of the country’s sugarcane growth is in Negros:

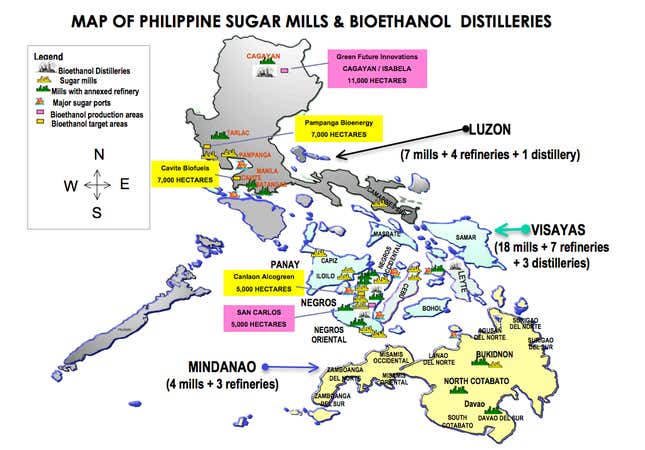

Both flooding and strong winds can uproot sugarcane. Even plants that withstand the storm’s impact are likely to yield less sugar as a result of flooding, though. Water-logging can also destroy sugar stocks at mills and refineries, many of which are also in Haiyan’s path:

This has happened in the past. In 2012, Typhoon Bopha (aka Pablo) killed an estimated 2,000 people and damaged sugarcane crops in Mindanao, a province of the southern Philippines. The sugar authority received reports of 8-10% sugar loss in one of the key sugar-milling districts. Though it was at the time the strongest storm ever to hit the Philippines, Bopha’s winds were only 295 kph, with gusts of up to 314 kph.

The sugarcane industry’s structure means any crop destruction from Haiyan will hurt the livelihoods of relatively more people than in more industrialized sectors. Sugarcane farming is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with 90% of sugarcane farms grown on plantations of 10 hectares (25 acres) or fewer. Most of those 62,000 sugarcane farmers are unlikely to have insurance.

Destruction would also be bad for the Philippines government, which sees sugar as an increasingly critical export commodity. The US is the primary export customer of the 2.2 tonnes (2.4 tons) of sugar it produces each year; 70% is consumed domestically. The government wants to up productivity and expand planting, instituting sweeping reforms so that its sugar business can compete with the likes of Thailand and Brazil. Those improvements will also help tamp down on imports of bioethanol, into which sugar is converted, a fuel source the country began shifting toward in 2007. The law now requires at least 10% bioethanol content in gasoline. A lack of distilleries, however—it only has three—means the Philippines has to import bioethanol to meet that goal. Damage to distilleries or to crops could mean it must buy even more bioethanol from abroad.