Amazon has everything it needs to make massively popular algorithm-driven fiction

Amazon is the Voldemort of book events—”our friends in Seattle,” the ominous euphemism goes. The Seattle-based company is famous and feared for its dual qualities of relentlessness and opacity. But what’s more important is how those qualities work in dangerous concert with a third pillar: Amazon’s data collection.

Amazon is the Voldemort of book events—”our friends in Seattle,” the ominous euphemism goes. The Seattle-based company is famous and feared for its dual qualities of relentlessness and opacity. But what’s more important is how those qualities work in dangerous concert with a third pillar: Amazon’s data collection.

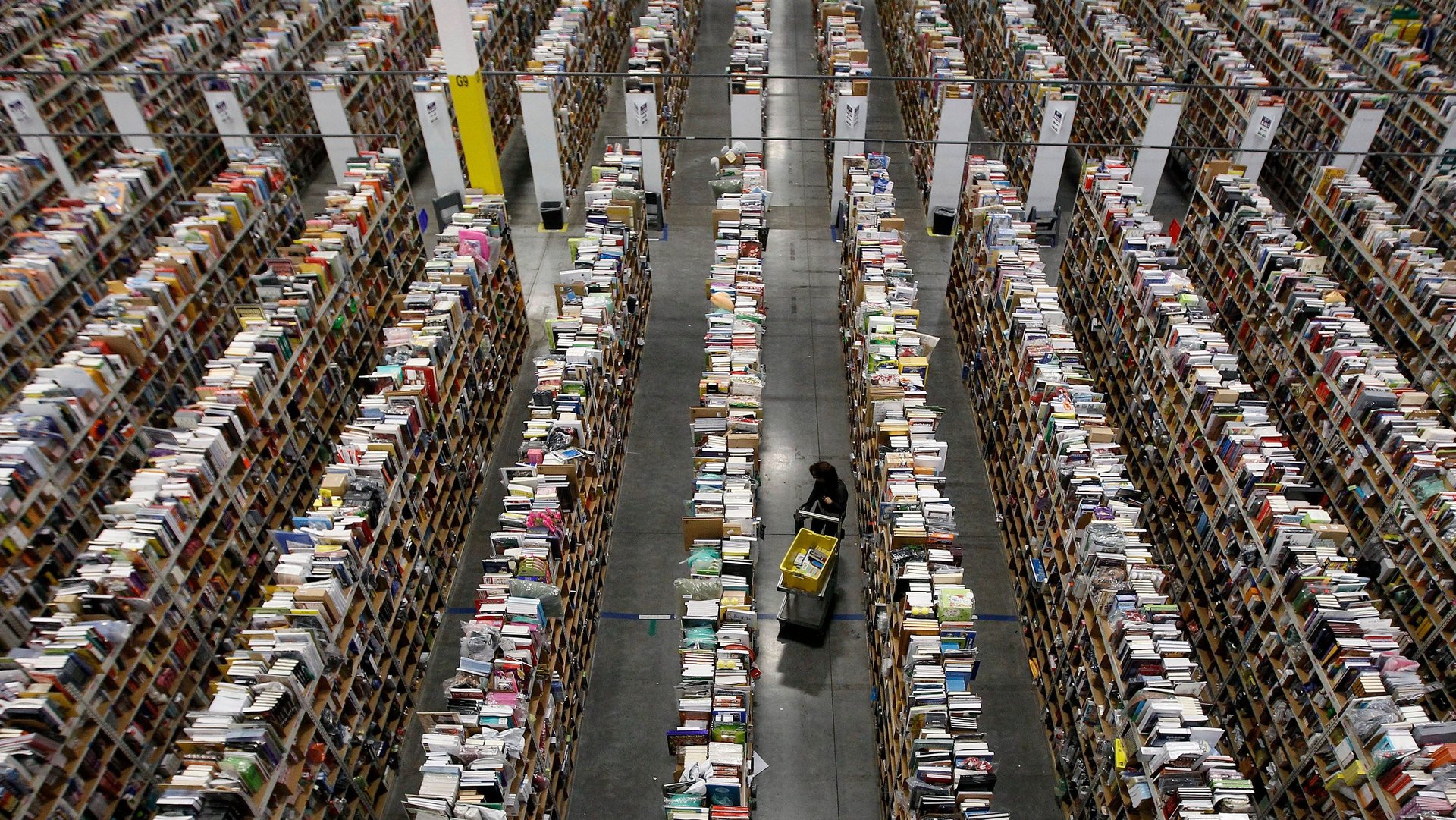

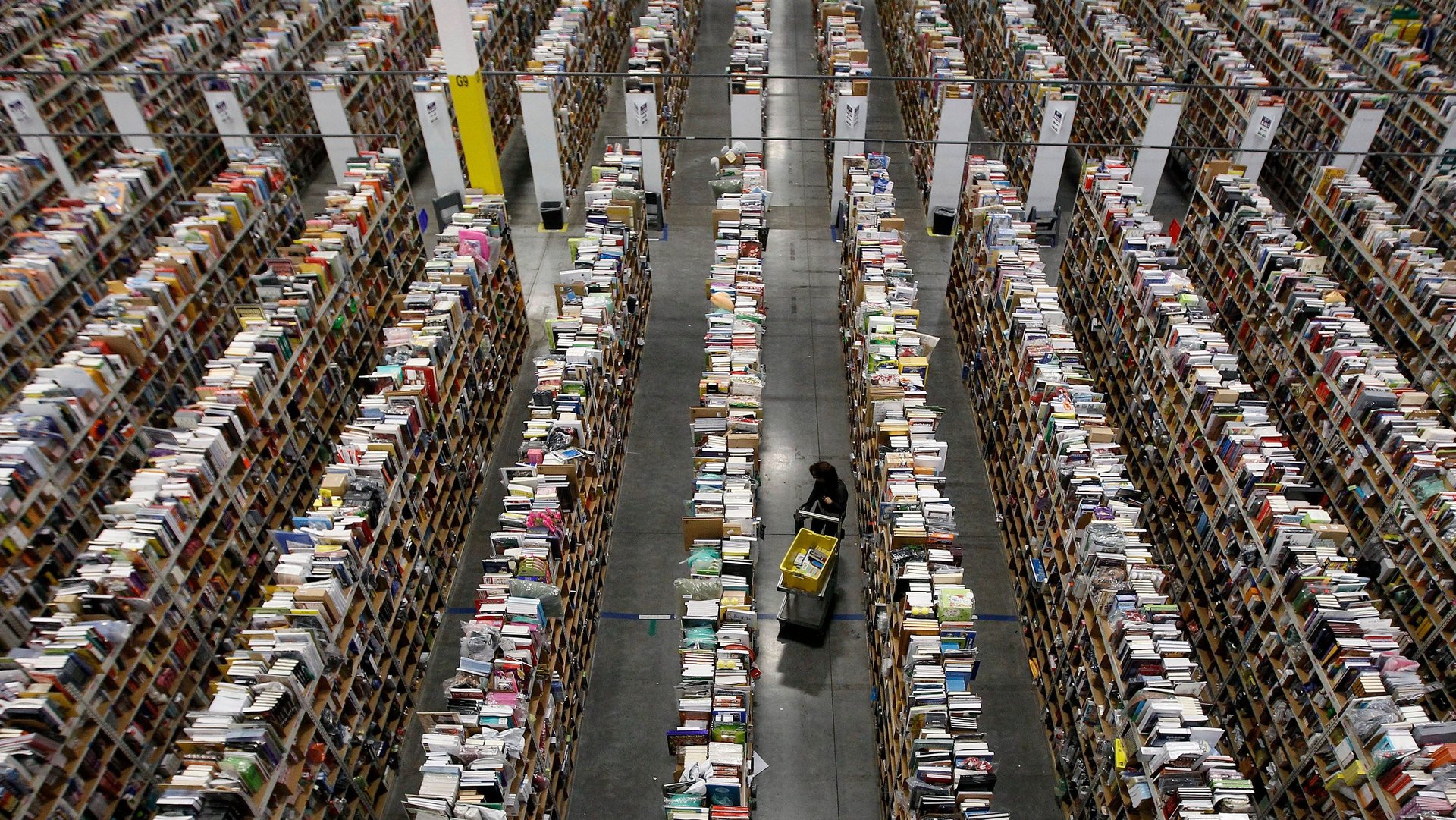

Amazon’s power in books extends way beyond its ability to sell them super cheap and super fast. This year, a little over 40% of the print books sold in the US moved through the site, according to estimates from Bookstat, which tracks US online book retail. (NPD, which tracks 85% of US trade print sales, declined to provide data broken out by retailer.) In the US, Amazon dominates ebook sales and hosts hundreds of thousands of self-published ebooks on its platforms, many exclusively. It looms over the audiobook scene, in retail as well as production, and is one of the biggest marketplaces for used books in the US. Amazon also makes its own books—more than 1,500 last year.

All that power comes with great data, which Amazon’s publishing arm is well positioned to exploit in the interest of making books tailored exactly to what people want—down to which page characters should meet on or how many lines of dialogue they should exchange. Though Amazon declined to comment specifically on whether it uses data to shape or determine the content of its own books, the company acknowledged that authors are recruited for their past sales (as is common in traditional publishing).

“Amazon Publishing titles are thoughtfully acquired by our team—made up of publishing-industry veterans and long-time Amazonians—with many factors taken into consideration,” says Amazon Publishing publisher Mikyla Bruder, “including the acquiring editor’s enthusiasm, the strength of the story, quality of the writing, editorial fit for our list, and author backlist/comparable titles’ sales track.”

A reader’s touch

Amazon’s Kindle e-reader, first released in 2007, is a data-collection device that doubles as reading material. Kindle knows the minutiae of how people read: what they highlight, the fonts they prefer, where in a book they lose interest, what kind of books they finish quickly, and which books gets skimmed rather than read all the way through.

A year after the Kindle came out, Amazon acquired Audible. Audiobooks have been a rare bright spot in the publishing industry, with double-digit growth in total sales for the past few years. Audible now touts itself as the “world’s largest seller and producer of downloadable audiobooks and other spoken-word entertainment,” and its site has around 450,000 audio programs. As a seller, it has virtually no competition, though companies are beginning to wise up to that fact: In January, Google started offering audiobooks in its Play store, and in August, Walmart announced a partnership with Kobo, a Canadian digital book retailer, to offer audiobook subscriptions cheaper than Audible’s.

Like Kindle, Audible is a trove of data. Its app knows when you drop off and stop listening; when you speed up, perhaps because the reading is too slow; when you rewind, maybe because the reading is too fast or the content is too confusing; what passages you bookmark; and what time you put your books on “sleep.”

In 2013, Amazon bought still another massive dataset: Goodreads. The popular social network for readers today gives Amazon access to 80 million profiles on book preferences, which it could theoretically layer on top of actual reading behavior. Goodreads users obsessively record what they’re reading and when, as well as what books they want to read but haven’t. They also leave text-heavy reviews, ripe for data-mining. And they make friends, giving Amazon granular data on reader networks and relationships.

All of that data is linked through Amazon accounts, which have detailed information about what and how people buy.

Self-starters

With its self-publishing arm, Amazon has created a system that enforces still more data collection. It hosts hundreds of thousands of self-published authors through Kindle Direct Publishing, though the exact number is hard to know. Amazon is the reason that self-published writers, particularly in romance and fantasy, have been able to make a living without having to enter the arduous lottery of getting plucked by a publisher.

But in return for royalty rates much higher than the industry standard, Amazon keeps its authors close. It heavily promotes books from self-published authors that agree to be exclusive with Amazon. But authors are paid out of a collective fund of money set by the company, based on the number of pages read from their books out of all pages read through two Amazon reading subscriptions. Historically, Amazon has been slow to address the rampant scamming invited by this system, though it occasionally steps in to implement sweeping automatic bans or penalties that can also hurt genuine authors.

While often leaving its authors out in the cold, Amazon is forever strengthening its get-to-know-you machine on the backs of their efforts. The more hours people spend reading these books that cost Amazon next to nothing, the better the data. The better the data, the better the site’s recommendations. The better the recommendations, the better the product: Amazon itself.

Content machine

Amazon isn’t always shy about what it does with its data. The company puts out a weekly list called Amazon Charts, which highlights bestsellers alongside something called “most read”—not what people buy, but what digital books they actually open, because Amazon knows when people do that. Amazon’s brick-and-mortar bookstores have a “page turner” shelf, advertised as books that readers have finished in three or fewer days on Kindle. At a May event in Newark, New Jersey, Audible honored top audiobook narrators with dinner and a ceremony. Super-fans of the narrators were invited, too, their enthusiasm gleaned from listener behavior.

Amazon could easily use all of its data for its own publishing efforts. In terms of awards and accolades, Amazon Publishing hasn’t reached the level of mainstream fame or critical success as the company’s movie and TV studio. But on Amazon.com, it’s certainly making a mark.

Books from Amazon Publishing imprints are overwhelmingly downloaded as ebooks via Kindle. Which has a curious side effect: The New York Times, the most prestigious and arguably most important of the US bestseller lists, doesn’t count them. Whether pointedly directed at Amazon or not, the Times doesn’t count “e-books available exclusively from a single vendor.” (“We include sales that we are able to confirm according to our standards,” Danielle Rhoades Ha, communications vice president for the Times, writes by email, though she declined to elaborate.) The Washington Post, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal do include Amazon ebooks on their bestseller lists.

This opacity in how Amazon’s books are actually doing could give Amazon an advantage. To publishers, Amazon’s lack of books on the New York Times bestseller lists may seem like clear evidence of its failure as a publisher. Meanwhile, over on Amazon.com, books from Amazon Publishing’s imprints regularly take up three or four spaces the week’s Top 20 bestselling fiction books list. In a recent week, it was six. What seems to outsiders like a flopped experiment could really be data collection for something altogether different.

Formulaic endings

Book lovers tend to focus on the fact that the book apocalypse—that is, the wholesale replacement of print books with ebooks—has largely failed to materialize. But to the extent that books have transitioned to digital, the flow is almost entirely through Amazon. With its data and power, the company could make books designed specifically to keep people reading and buying, and with its impressively wide-reaching marketing strength, it could get those books in front of hundreds of millions of people with credit cards.

After all, there’s precedent. Netflix, which also has access to vast troves of data on its customers’ most granular consumption habits, has used data to inform its productions; one director even said he took notes from its algorithms. So maybe Amazon is irreparably altering popular American culture by creating a new landscape of literature driven by data and algorithms, using notes from its own statistical model-cum-editor. Or maybe it isn’t. But there should be no doubt whatsoever that it could.