In 1822, a ragtag band of eight inmates escaped from a brutal penal colony in Tasmania, Australia. They descended upon the island’s hostile pine and myrtle forests, but quickly found themselves lost and starving.

One of the convicts, a former sailor called Robert Greenhill, proposed eating the others—the so-called “Custom of the Sea.” “He had seen the like done before,” the sole survivor, Alexander Pearce, later recounted, “[and said that] it tasted very like pork.” Two men left the gang.

The remaining men did kill and eat their fellow escapees—the first for having flogged other prisoners; the second after drawing lots and saying his prayers. The remaining four—John Mather, Mathew Travers, Greenhill and Pearce—then found themselves faced with a troubling reality: eat, or be eaten.

This tale is not well-known among those who lack a working knowledge of Australia’s penal history and folk heroes. But a “hidden homage” to them, thinly disguised by the labels ‘M,T, G, P,’ appears in a forthcoming economics paper in the journal Games and Economic Behavior, with the title “How to choose your victim.”

The paper, by authors Klaus Abbink and Gönül Dogan, is an experiment-based look at how mobs choose their victims. Abbink, from Australia’s Monash University, specializes in experimental and behavioral economics; Dogan, from Germany’s University of Cologne, works on anti-social and unethical behavior, particularly in a corporate setting. As the authors write: “We find that subjects frequently coordinate on selecting a victim, even for modest gains. Higher gains make mobbing more likely.” People will form a mob, in short, to get something they desire—and there’s a pattern to the way they pick their victims. The paper found that those who are well-meshed within a group were less likely to become its target, while those indicated to the others as being poorer or richer or otherwise arbitrarily different were more likely to face the wrath of the mob.

Within these experiments, players were given a letter—M, T, G, or P. To the 860 participants, this set of consonants likely appeared totally random. But a clarifying footnote reveals their grisly origins, and their relation to the study: “All victims were chosen in decidedly non-random ways. This story is one of the great Australian foundation myths, and it was an inspiration for this study … We are confident that none of our Northern European subjects made that connection.”

And what happened to the four men in the woods? They spent their days in terror of being slaughtered, sleeping with axes under their pillows. Various members of the gang teamed up in attempts to kill the others or save their own skin, until just two were left.

Finally, as the Australian Age reports: “Pearce and Greenhill struggled on for eight days, playing cat and mouse with each other, desperate to stay awake, fearing that the other would attack him if he closed his eyes and nodded off. It was Pearce who kept awake long enough to grab the axe and kill the sleeping Greenhill with a blow to the head.”

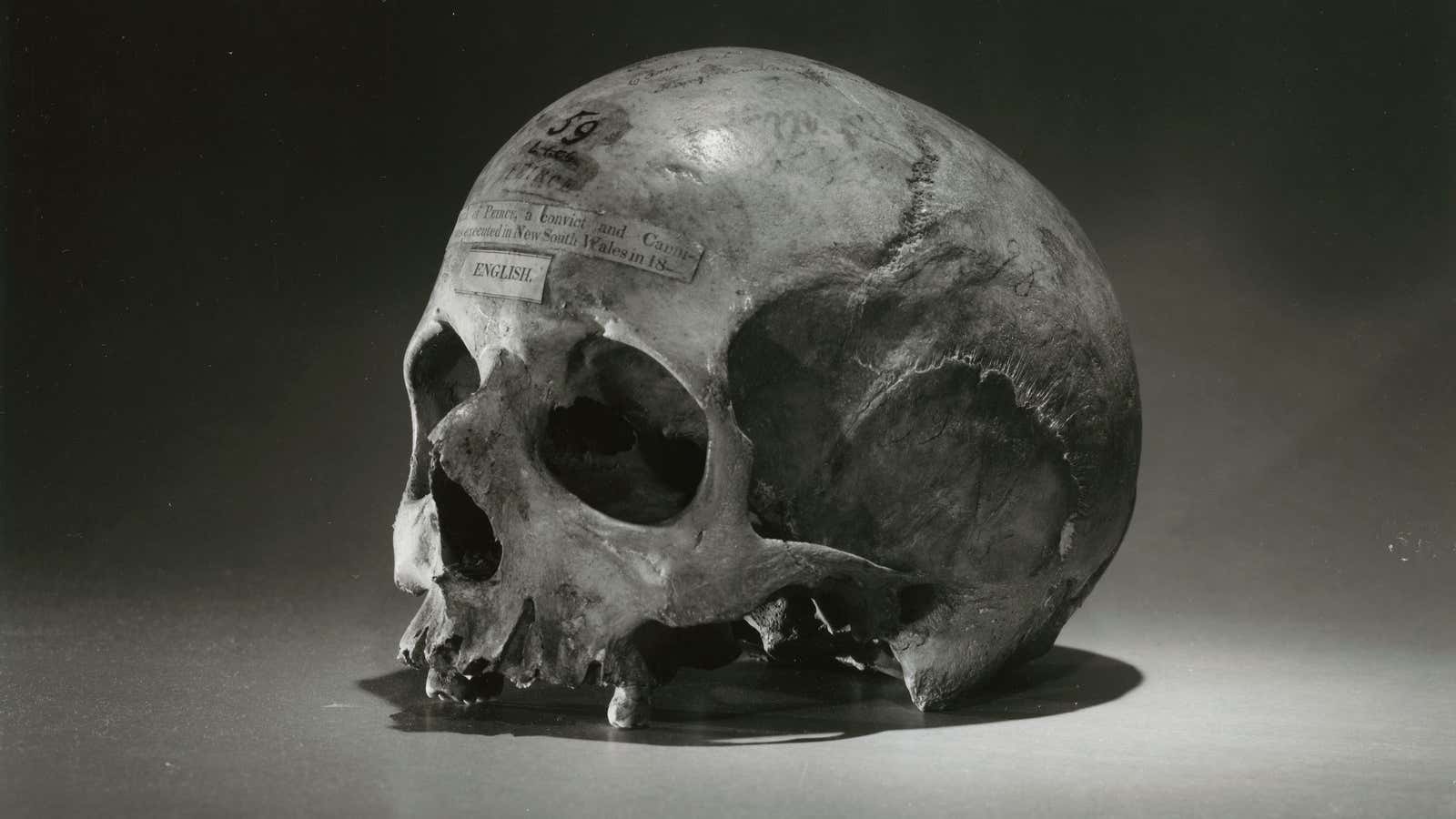

Pearce was eventually found and returned to prison. Two years later, he escaped again and killed and ate his companion escapee—despite having other food. (Perhaps he’d developed a taste for human beings.) He was tried, convicted, and hanged for murder. The lesson here? Even if your worldview is eat or be eaten, you’re still going to wind up dead.