A shrinking Japan worries about its people leaving—but not about foreigners coming in

Countries with vast populations—like India and China—can afford to lose large numbers of their people to other countries as migrants or expats, depending on your preferred nomenclature. Countries with small and shrinking populations can’t be so blithe.

Countries with vast populations—like India and China—can afford to lose large numbers of their people to other countries as migrants or expats, depending on your preferred nomenclature. Countries with small and shrinking populations can’t be so blithe.

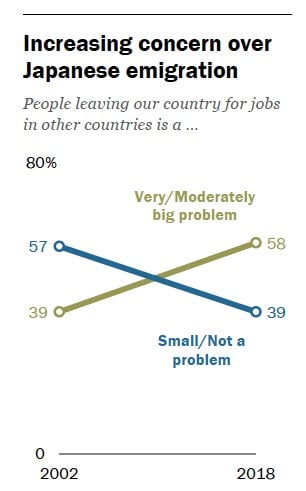

In Japan, with a population of 127 million shrinking at an average rate of 1,000 people a day, people are pretty worried about it, in fact. In a survey of 1,016 Japanese respondents conducted between May 24 and June 19, Pew Research Center found that nearly 60% of people surveyed called Japanese nationals leaving to work overseas a “moderately/very big problem,” up from 39% in 2002. About 1.3 million Japanese are living abroad, according to the government.

While immigration is growing faster than emigration, the net increase from it has been small so far and unable to offset the shrinking due to a low birth rate and rising elderly population. And given Japan’s desire to preserve its culture and language, the country would clearly prefer to keep the Japanese people it has, rather than replace them with foreigners—although it’s slowly bending on that front too.

When it came to how much immigration to have, nearly 58% say that immigration should stay around where it is at the moment, while 23% wanted it to rise (the Pew survey last year didn’t ask in as much detail about immigration, so it’s unclear how the view has changed). Still, given that immigration has visibly increased in Japan in recent years, voting for the status quo could mean that many Japanese are OK with the increases in immigration that are taking place. Only 13% wanted immigration to go down. Meanwhile 59% said that immigrants were making Japan stronger because of their work and talents, while less than a third said they were a burden on society.

Of more than 2.2 million foreigners living in Japan, some 1.3 million are workers (paywall) as of 2017, a 17% increase from the previous year. And that could rise further if legislation to create new work-visa categories approved this month by prime minister Shinzo Abe’s cabinet is passed by the end of the year.

Japan’s lower house of parliament began discussing the draft law on Tuesday, and government sources told Nikkei that that somewhere between a quarter of a million and nearly 350,000 workers (paywall) could come to work in Japan under the law, in 14 critical industries.

A Kyodo poll found 51% of Japanese supported the new work-visa law—possibly because the administration doesn’t really talk about it in terms of immigration reform. And in fact, the new work visas for blue-collar workers wouldn’t allow people to bring their families and limit the time they can stay.

Still, the proposed law would give more protections to blue-collar foreign workers, who presently work on trainee visas, which aren’t official work visas, says Misa Matsuzaki, the founder of Work Japan, an app that aims to connect such workers already in Japan with jobs, allowing them to bypass exploitative employment brokers. Matsuzaki was among those advising the Japanese government on the draft law.

The planned visa is fairer to workers in that it allows them switch employers, she told Quartz, which the trainee visa doesn’t allow no matter what troubling issues arise in the work situation.

A separate skilled-worker visa would allow people to bring families and eventually apply to be permanent residents. Both groups of workers have to learn Japanese. A Nikkei survey (paywall) also showed support for Abe’s plans to bring in more foreign workers.

Apart from needing workers for everything from convenience stores to caring for the elderly, Tokyo will host the summer Olympics in 2020. It needs construction workers to build the facilities, and also wants to welcome tourists with English-speaking taxi drivers and guides.

Update, Nov. 14: This story was updated with new estimates about the number of workers that could enter under the law.