Kites, paper, explosives, the compass, movable type—those were all invented in China. But after several millennia of dazzling the world with innovation, China’s technological brilliance has dimmed. For the Chinese government, that’s become an issue of national pride. It now plans to become an “innovation-oriented nation” by 2020 and a “world science and technology power” by around 2050, according to a report by Nesta (pdf, p.19), the UK’s innovation foundation. The report notes that local governments subsidize patent costs and slash corporate taxes for companies that generate numerous patents. And for managers at state-owned enterprises, hitting government-set patent application targets is critical to earning promotions.

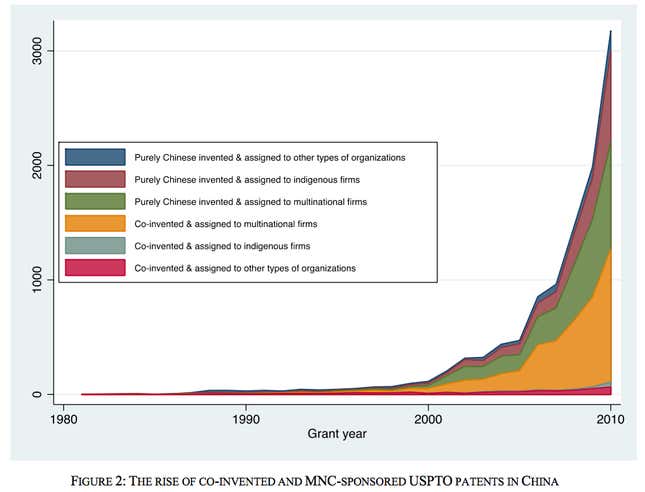

The funny thing, though, is that Chinese inventors are already producing world-class patents—a lot of them. In 2010, they earned more than 3,000, according to recent research by economists Lee Branstetter, Guangwei Li and Francisco Veloso. That’s more than three times the number just four years earlier—and a 46-fold rise on 1996. If you agree with the report’s authors that US patents are an indicator of innovative activity, China’s well on its way to becoming a “technology power.”

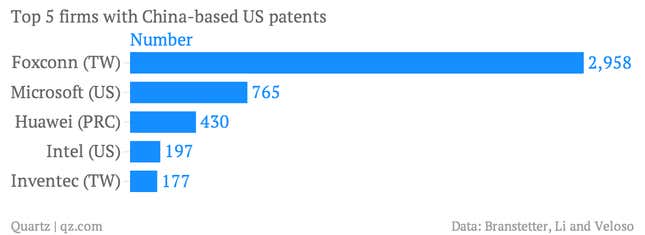

There’s a catch, though. By and large, Chinese companies aren’t the ones benefiting from this. Here’s a look:

“Our study suggests that the increase in U.S. patents in [China] are to a great extent driven by [multinational companies] from advanced economies and are highly dependent on collaborations with inventors in those advanced economies,” says the report’s authors. The chart below shows how fruitful some of those collaboration have been:

Why would the China-based teams at Hon Hai and Microsoft be besting Huawei at producing patents? For one thing, there are still “relatively few individuals who have become capable of directing a world-class R&D effort… without many years of exposure to multinational best practice,” as the authors put it. Savvy leaders at multinational companies have used technology advances to guide teams around the world to collaborate with divisions inside China, while benefitting from the cheaper labor.

This, say the researchers, suggests that fears that Chinese innovation is threatening the technological leadership of the US and other advanced economies are overblown.

This isn’t necessarily bad for China, though. It benefits from bumped-up employment and investment, while enhancing its native know-how.

Getting the most out of this know-how is important, too. This increasingly sophisticated division of R&D labor among multinationals also helps make its Chinese workers more productive. The study found no difference in quality between inventions a multinational generated in China versus in its home country. And when multinationals can innovate more cheaply, it’s easier for them to sell goods competitively in China and other emerging markets.