Over the past 100 years, the way Americans eat has drastically changed. These aren’t just shifts in preference: War, technology, and globalization have together woven a tapestry of American cuisine that is as diverse as the country itself.

The United States Department of Agriculture has been recording data on the production of food since its creation in 1862, and detailed data is available going back to the early 20th century. Quartz downloaded more than 100 years of USDA data, and used an algorithm to detect the most significant anomalies. Narrowing the results showed three eras that defined the US food economy: World War II, post-war industrialization, and the modern era.

The necessities of feeding soldiers fighting across oceans meant shelf-stable protein like peanuts and dried milk became crucial. After the war, soldiers brought back new food preferences, and a growing population meant the US simply had to make more food.

Today, we’re living in a time where new culinary trends can create billion-dollar businesses. It’s no longer a game of making enough food, but the right food.

World War II

Peanuts

Peanuts are the perfect food for war.

While peanut butter was gaining popularity at the turn of the 20th century in the United States—mainly on the tables of bespoke tea shops—the US military was refining peanut oil for its glycerine to make explosives.

The byproduct of extracting that peanut oil was then turned into flour and soup, according to Andrew F. Smith’s book on the crop, Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea. But despite its versatility, the peanut was still a smaller domestic product, with $71 million of peanut oil being produced in 1941 ($1.2 billion adjusted for inflation).

Then came 1942. The US had joined World War II, and the peanut’s use as a weapon and shelf-stable food made it indispensable to the war effort.

Secretary of agriculture Claude R. Wickard asked farmers to plant 5 million acres of peanuts in 1942, and the government lent them money to purchase equipment to harvest the crop. The request was reiterated in 1943 after only 3.5 million acres had been planted; Wickard urged planting 5.5 million more.

The peanut was crucial “in winning the war and perhaps in the peace to follow,” Wickard said in 1943. “No doubt it will feed the famishing world.”

While the peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich had been a staple food during the Great Depression, the invigorated peanut market and inclusion of peanut butter, jelly, and shelf-stable bread in military rations turned the sandwich into an American classic.

The peanut industry was heavily subsidized after the war as well, and since imported sugar and chocolate were in short supply during the war, peanuts had by then been adopted domestically as a snack and candy ingredient. Their popularity has been growing ever since.

Dried milk

Dried milk was another product made indispensable by the necessities of war. Regular milk was heavy and spoiled easily, but the powdered version could last far longer, and fresh water was easier to come by than cows.

Before the war, powdered milk was a byproduct of making butter, says Kendra Smith-Howard, author of Pure and Modern Milk. It was mainly used as animal feed, though sometimes bakers would include it in recipes. When the Great Depression hit, powdered milk was cheap and shelf-stable, so it was rationed.

During World War II, the military needed a dairy product that wouldn’t spoil. Powdered milk became a vital part of the war effort, since it could be reconstituted into milk or made into ice cream.

After the war, the government still bought massive quantities of dried milk, and it still does for school lunches and humanitarian efforts.

Ice cream

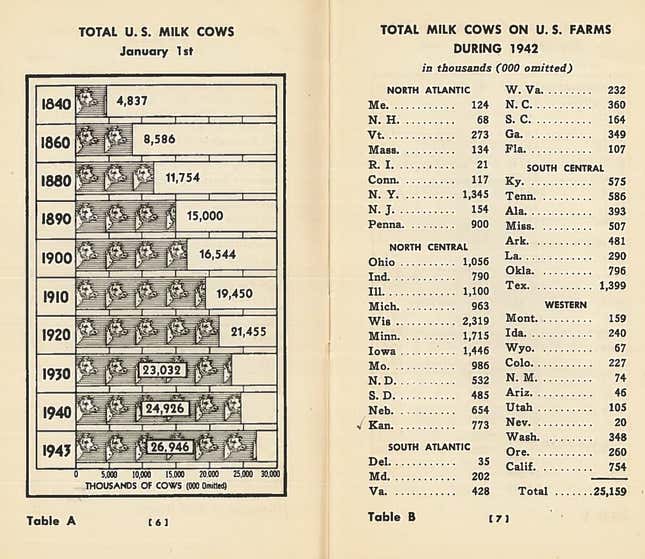

In addition to dried milk, World War II caused the greatest demand for fresh milk in the United States’ history, according to a Milk Industry Foundation document from 1943.

“More than 26 million U.S. cows on three quarters of the nation’s six million-odd farms are involved in this effort to produce a 57 billion-quart record goal in 1943 — enough milk to fill a border of quart bottles 200 feet wide along all our nation’s coast lines,” the pamphlet read.

By the end of the war, ice cream was used as a morale booster for the troops. The US Navy spent $1 million converting a barge into a floating ice cream factory, which would make and deliver ice cream to ships that couldn’t make their own.

When Hitler was defeated in 1945, America celebrated the only way it knew how: ice cream. Regulations limiting the domestic consumption of dairy meant that ice cream producers had their supply diverted to milk and cheese for soldiers during the war. After the war ended, the regulations were lifted and ice-cream production skyrocketed from less than 300 million gallons in 1938 to over 700 million in 1946, starting a new era for ice cream in the US.

The Pentagon would later mandate that troops must be fed ice cream no fewer than three times per week.

Industrialization

On-farm slaughter

Efficiency on the mid-century farm no longer meant doing everything in-house. The scale afforded by delineating the raising of animals for food from their eventual slaughter meant that it made financial sense to specialize in one of the two fields.

“After World War II, two developments occurred,” Patrick Boyle, former CEO of the American Meat Institute, told PBS Frontline. “The local butcher shop began to expand into grocery stores and regional grocery chains. At the same time, we developed technology to ship refrigerated foods. And with the advent of grocery stores wanting to buy their meat from a single source, and with the ability to ship processed meat as opposed to live animals in rail cars, the packing houses moved out of the metropolitan areas and built new facilities in the heartland, close to where the animals were being raised.”

Those new facilities were a far cry from the family farms that had long dominated the Midwest. They were larger businesses that could afford to process the tens of thousands of animals being raised on feedlots.

Cheese

Pizza, an American staple, came to the US with soldiers stationed in Italy after World War II. In the following decades, pizza joints grew to such massive numbers that by the mid-1980s, mozzarella was the most popular cheese in America. The industrialization of dairy production, as with butter, made it possible for America to break 1 billion lbs of mozzarella in 1985.

“Mozzarella has been this engine that has driven per capita consumption of cheese in the United States,” food historian Paul Kindstedt told Quartz. “It’s been increasing just relentlessly.”

Kindstedt says that after World War II the prosperity in the US allowed more frequent dining at restaurants, and the expanded palates of soldiers coming back from Europe led to the birth of American pizza shops. Pizza was the perfect mix of inexpensive, versatile, and delicious.

Pizza shops need lots of mozzarella, which means the amount of cheese the US needed to produce increased dramatically.

“It is a very low-margin business, and so it’s intensely competitive and that just fuels an emphasis on efficiency and higher technology to lower costs,” Kindstedt said. “This is a biological process, cheesemaking and fermentation, and there’s been a lot of science that has had to happen to make that possible.”

Mozzarella-makers in the US can process 5 million to 10 million lbs of milk a day, to produce 500,000 lbs of cheese, he said.

And Americans eat it up. The US consumed 39 pounds per person in 2017, which makes sense given the nearly 13 billion pounds the US produced last year.

Butter

American food doesn’t exist without butter: Mac and cheese, popcorn, literally fried butter balls—all need butter to attain their most beloved forms. Thus as the US population grew, so did its need for butter. And as higher-powered machinery was able to replace the butter-churning equipment of smaller farms, the industry began to consolidate from farms to factories. Full-fatted cream began to be shipped to plants, where it could be processed into butter and buttermilk, the liquid expelled as the cream’s solids form into butter. As a result, the number of plants making butter fell from nearly 4,700 in 1940 to just over 600 in 1970.

Modern food

Chickpeas

The chickpea is one of the US’s most global foods. Until tariffs levied by India in the past year, the US exported more than half of its chickpeas to countries like India, where the legume is a dietary staple.

Domestically, chickpea consumption has seen a meteoric rise for one reason: hummus. The chickpea market is currently owned by Sabra, which holds 60% of the hummus market.

Though Sabra was founded right around when chickpea production started to climb in America, the legume-based dip didn’t hit a fever pitch until the late 2000s, when PepsiCo bought half the company and started distributing hummus throughout the US.

Now a new crop of hummus startups are starting to diversify what the legume can be used for, the US Dry Pea & Lentil Council told Quartz. Protein-packed chickpea juice is being billed as a vegan replacement for eggs in meringues, and there is even a chickpea-based ice cream.

Hops

There are more independent breweries now than there were at any point before in American history—even more than existed before Anheuser-Busch took over the world of beer. These independent breweries make a wider variety of beer, but especially tend to focus on hop-heavy India Pale Ales. This means more hop production.

This renaissance in beer has made the US the biggest producer of hops in the world. In 2017, the US produced over 48,000 metric tons of hops, beating out Germany, which produced almost 42,000 tons.

Cuties

Perhaps no company has invented and dominated a food category as heavily as Cuties—the Band-Aid of citrus fruits. The founding of Cuties in 1990 and the rise of mandarin oranges and clementines—counted in the same category of “tangerines” by the FDA—showcases that rise to power. Other well-known brands include Halos and Darling clementines.

The easy-to-peel citrus first gained popularity after a freeze killed much of California’s citrus. Brands that would become Cuties and Halos were born (paywall) to fill the resulting citrus deficit.

Cuties’ popularity is credited to the fruit being sweet, seedless, and easy to peel: a trifecta of fruity convenience.