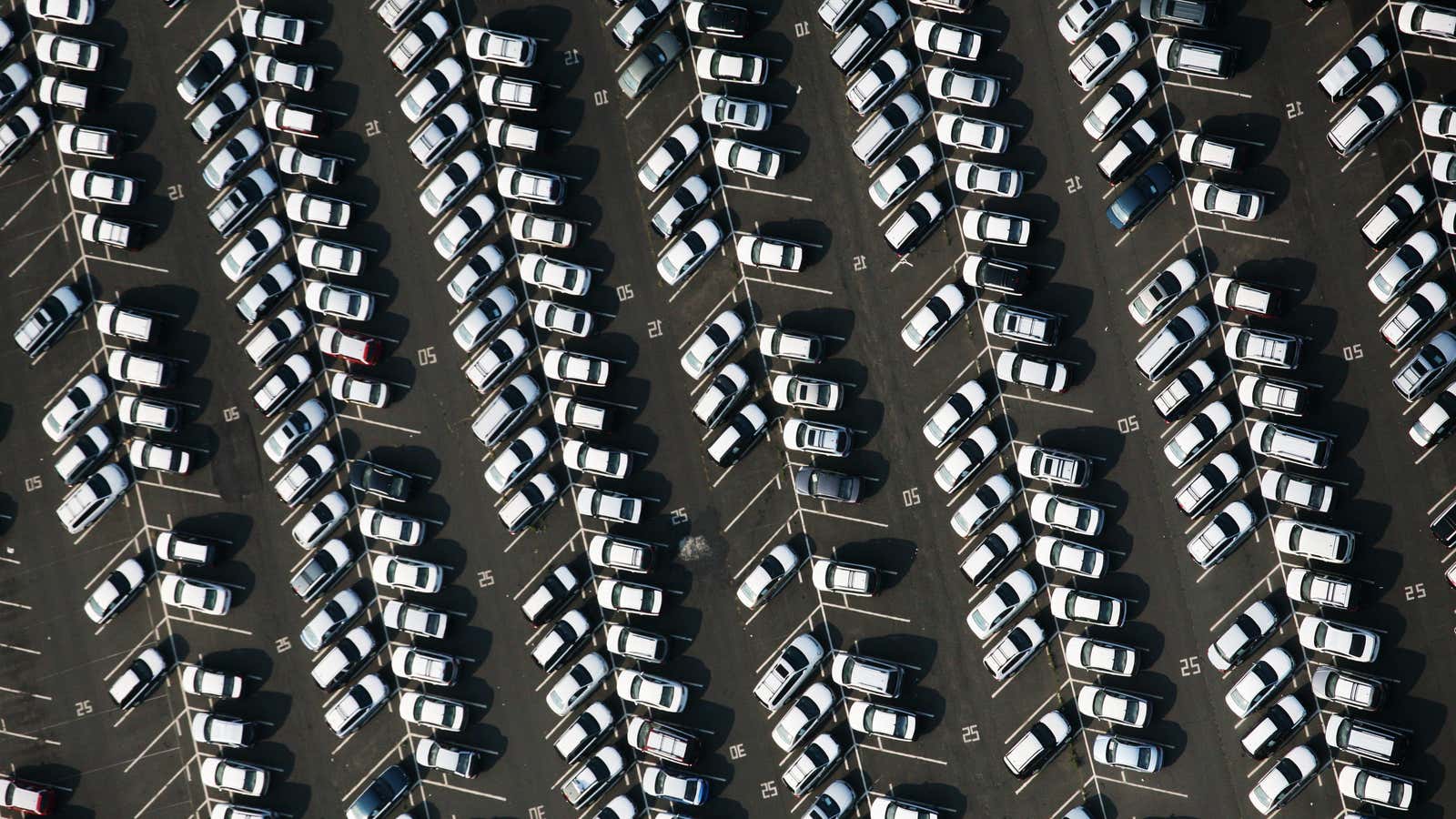

American cities have long been built around parking—less a result of need than of outdated regulations passed on by city planners and politicians. They’re now in the slow process of backing out of this error.

San Francisco has become the first major US city to propose stripping out minimum parking requirements for new housing, according to city supervisor Jane Kim who introduced (pdf) the legislation on Nov. 16. San Francisco’s 1950s parking rules had remained virtually unchallenged until the 1970s oil crisis prompted it to rethink its strategy. Today, the city is already restricting parking under its “transit-first” policy. This week’s proposed change, which will be voted on by the city’s board next week, will effectively formalize that policy city-wide.

San Francisco is not alone, but it’s the biggest city in the US by far to tackle its outdated parking rules. A database for minimum parking rules shows smaller cities across the country, from Colorado Springs to Hartford, are making similar moves.

The counter-example is Los Angeles. When LA approved its 2,265-seat Walt Disney Concert Hall in the 1990s, city officials required it to have garage spaces for 2,188 cars. The subterranean garage cost $110 million, about half the cost of the building, according to Los Angeles Magazine. Donald Shoup, a professor in the Department of Public Planning at the University of California, Los Angeles, described it as the pinnacle of poor planning, leaving the area desolate and public transit obsolete. “L.A required 50 times more parking under Disney Hall than San Francisco would allow at their own [music] hall,” he told the magazine. The city has yet to implement any major overhauls of its requirements for minimum parking.

All of this parking is the result of a slight misunderstanding. For more than half a century, the Institute of Transportation Engineers has had parking standards for buildings so developers can predict traffic needs. There are exact parking recommendations for everything from apartment buildings (1.6 spaces for every unit) to convents (0.1 spaces per residing nun) to fast-food restaurants (9.95 parking spaces for every 1,000 square feet). These suggestions not only rested on statistically dubious data (pdf), they were never intended to guide parking policy in cities. Their availability, and deceptive precision (pdf), meant they were often taken out of context from development plans meant for new, greenfield sites.

That’s been disastrous. Developers have been directed to spend billions of dollars on asphalt lots and garages that have deadened the life of downtowns, and wildly overestimated actual parking needs. One Dallas, Texas study (pdf) found the city’s peak parking usage still left the city with 30,000 empty spaces. Excessive parking is also expensive. Two urban environment researchers analyzed the 2011 National American Housing Survey data of the US Census and found about 16% of a housing unit’s monthly rental cost is attributable to the expense of building an urban parking spot. For the average renter that amounts to $1,700 per year, or $142 per month.

It’s probably not a coincidence that San Francisco is one of the first cities to ditch its devotion to parking. Silicon Valley’s transportation companies—Uber, Lyft, Tesla, Google’s Waymo—are betting on a future where personal parking is obsolete. They are pursuing a new mobility model, known as the transportation cloud or “transportation-as-a-service” (TaaS), which will allow self-driving cars to be deployed as fleets, or rented out as autonomous taxis when owners are not using them. Tesla plans to offer this service in a few years. Rather than sit idle for 95% of the time, fewer people will own cars in favor of shared, electric, autonomous transport hired by the minute, predicts (pdf) the Bay Area think tank RethinkX. It estimates TaaS will eclipse privately owned vehicles by about 2025 (give or take).

Not everyone buys this vision. And parking is still popular for many. Only 7% of US rental households lack cars, according to census data, and many residents demand more parking come with any new development. Paul Chasan, a San Francisco city planner, told The Examiner that developers will still have a hard time getting projects approved without parking. “They operate under political constraints where the neighborhoods will probably pressure them to build parking,” he said.

Looking for more in-depth coverage from Quartz? Become a member to read our premium content and master your understanding of the global economy.