Bird is being sued for trespass in a class action complaint filed Nov. 30 by a property owner in Santa Monica, Calif.

John Lautemann is suing Bird for trespass and nuisance, alleging the dockless electric scooter company is harming property owners, “as e-scooters are flagrantly left on their property or in an unsafe manner on the sidewalks adjacent to their property.”

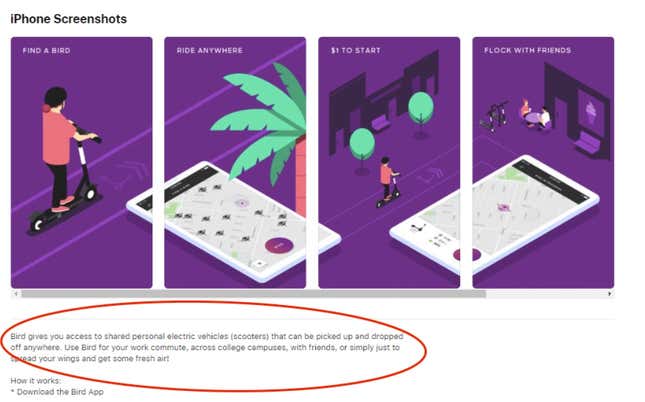

The crux of Lautemann’s allegations is that Bird “prioritizes users’ convenience over property owners’ rights,” with a policy that encourages Bird users to pick up and drop off their scooter “anywhere.” The complaint includes a screenshot of the Bird app in Apple’s app store that advertises this policy, which I’ve circled in red below:

The complaint argues that Bird’s $2 billion valuation is premised on this leave-it-anywhere business model. This is (1) because the dockless model makes the service more convenient for consumers, who can end a ride at their destination rather than a parking hub several blocks away, and (2) because the costs of running a docked scooter service would be significantly higher, between the price of installing docking stations (tens of thousands of dollars a piece) and cost of redistributing scooters from empty ports to busy ones throughout the day.

While Bird is getting rich—or at least a rich valuation—off this setup, Lautemann’s attorneys argue that its haphazardly parked scooters are cluttering up roads and walkways. The lawyers allege these actions are “exposing property owners to potential legal liabilities and burdening property owners with removing Bird’s e-scooters from their property or adjacent sidewalks.”

Lautemann claims Bird scooters have repeatedly been left on his property since this past summer, “in the area reserved for parking cars, near the entrance to the building, in the courtyard, and in the corridor.” The company “did not seek consent from Plaintiff before operating in the area.”

It’s unclear whether Lautemann asked Bird to remove the scooters, and his lawyers didn’t reply to a request for comment. But, the complaint asserts, “Bird e-scooters are GPS-enabled, so Bird knows or should know that e-scooters have been placed on private property without obtaining consent.” Bird declined to comment.

The argument that Bird should know where its scooters are left because of their GPS capabilities has implications potentially much broader than scooters on sidewalks. There are arguably lots of things any company that collects data on its product and users “knows or should know,” where “should know” seems to mean “should know by virtue of having the data.” Bird knows or should know where scooters are left; Airbnb knows or should know when properties are rented illegally; Amazon knows or should know when banned products are sold on its site; Facebook knows or should know when and how fake news is distributed.

The Bird complaint is, in that sense, a microcosm of the debate over what responsibilities technology companies have as custodians of our data. Electric scooters make it a little more tangible, relatable, and easy to follow.