“Don’t switch off your phone because I’m coming home,” were the last words Dolfina said to her mother, in March 2016.

A week later, her mother received a call from another phone number in Malaysia, where Dolfina, 30, worked in the costal town of Klang. This time, the call was from an employment agency she had never heard of before. Her daughter was dead, they said, and her body would be shipped back to her childhood home in East Nusa Tenggara, an impoverished Indonesian farming province.

Dolfina is one of the many women who fall victim to human trafficking in Malaysia, a top destination for Indonesian migrant workers. More than half of the estimated 1.9 million Indonesians in Malaysia are undocumented.

Accompanied by a Malaysian certificate of death by natural causes, Dolfina’s body arrived home a month after her last phone call. She had bruises and stitches at the back of her head, and more stitches traced a line from her neck down to her stomach and genitals. Her family suspects that she was also a victim of organ trafficking.

After her brother reported that Dolfina’s body had been mutilated, local Indonesian police opened an investigation. In Dec. 2016, one of Dolfina’s traffickers, Sefriadi Safroni Sinlaloe, was convicted of taking Indonesian citizens outside of the country for the purpose of exploitation. He received an 11-year sentence.

How to stop human trafficking

Workers who are trafficked without legal immigration paperwork are entirely dependent on their traffickers and employers, and therefore vulnerable to abuse. The invisible nature of trafficking also makes it a challenge for law enforcement; there is rarely physical proof that a victim is on her way to being exploited, until it’s too late.

In some ways, Indonesia’s efforts to fight human trafficking fall short of international standards. The country’s 2007 anti-trafficking law requires proof of force, fraud, or coercion to constitute a child sex-trafficking crime, which is inconsistent with international law. Corruption among Indonesian officials enables many traffickers to operate with impunity. And law enforcement often aren’t familiar with the signs of trafficking.

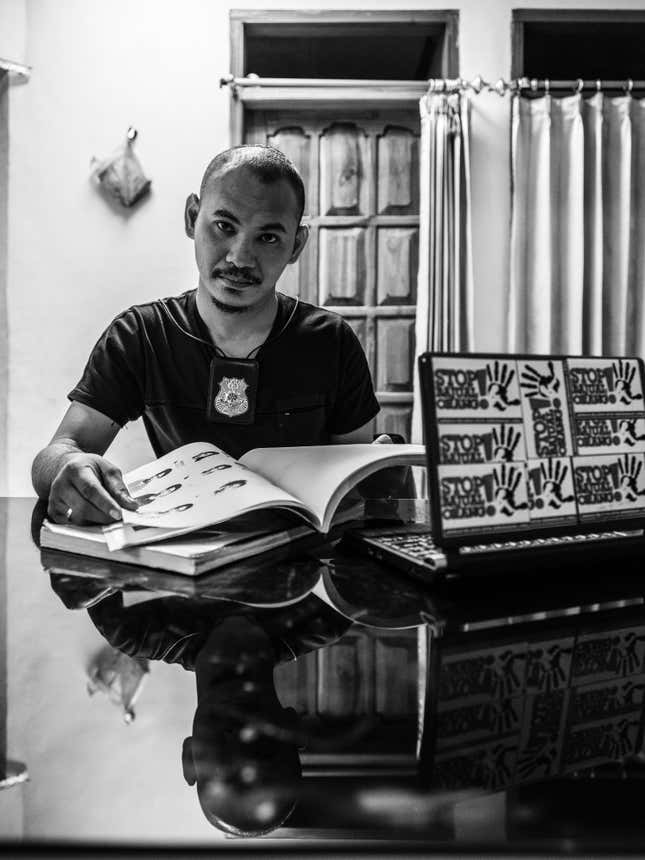

Nevertheless, efforts are being made to prevent cases like Dolfina’s. Police officer Ruddy Soik, a member of the human trafficking unit of East Nusa Tenggara, has been working on stopping human trafficking since 2009. He says he vowed to stop traffickers from recruiting women from his district after his first case, a trafficked village girl named Juliana who also died in Malaysia. He is proud to say that in 2018, his unit caught nine traffickers.

When I met him at his home, Soik showed me his human trafficking cases. The thick files are stuffed filled with details and images of Indonesians who left with a promise and came home either dead or abused. One woman named Adelina Sauk died after being allegedly starved, abused and forced to sleep outdoors with her employer’s dog in Penang, Malaysia.

After Sauk’s death, Soik worked with Malaysian authorities to arrest her employers and charge them with murder and the illegal employment of a foreign worker. Both are awaiting trial.

Soik has received death threats for his work. But he says the hardest thing is changing the mindset of Indonesian parents, who often give their daughters to traffickers as migrant laborers. He cannot blame them, he says: In their region, farmland is getting drier, villages are getting poorer and the lure of hope in Malaysia seems brighter every day.

Climate refugees

Changing weather in rural Indonesia is forcing poor people abroad, says Dolfina’s father Mikhael. In their village, which has no electricity or running water, the seasonal rains have been coming later. Drought and fires have made farming impossible, he says. Many villagers have switched to mining local minerals, although the profits are scanty.

Global warming is a driver of Indonesia’s human trafficking problem, says Renard Siew, a Malaysian advocate for climate change mitigation in the Al Gore-founded Climate Reality Project. “Most women in Indonesia are involved in smallholder farms…And I do observe that some of them are forced to move towards areas with more favorable climatic conditions when agricultural yields have suffered as a result of prolonged droughts or floods on the other end of the extreme. It is really about survival more than anything else.”

In Nov. 2013, a stranger who introduced himself as Johan Pandi came bearing gifts and promises for Dolfina. He asked Mikhael for permission to take the 27-year-old single mother to Malaysia to work as a maid. Her parents saw it as an opportunity for a better life, and agreed.

Dolfina left with the trafficker, who gave her a fake identity card and passport. One common issue in human labor trafficking is the failure of the authorities to monitor for proper travel documents.

When Dolfina called home from Malaysia for the first time, she said that her employer was good to her and she would be able to send home a million rupiah (about 69 US dollars) after a few months. So when another recruiter came to their village, her parents willingly sent her sister Maria to Malaysia, too.

Maria’s trafficker said that she, too, would work as a maid. But her father says she has ended up laboring on a palm oil plantation. Last time Maria called home after Dolfina died, she was scared, he adds.

She told him that she and other undocumented workers were in hiding from raids by Malaysian immigration authorities. Like Dolfina, she instructed her family to keep their phone on, and to wait for her call. Her father is still waiting for the phone call.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center.