The truth about drinking is going to disappoint you. Not because it’s scary, but because it’s still inconclusive.

There’s no amount of routine drinking that will definitively kill you (although acute alcohol poisoning can be fatal). Though the data suggest drinking alcohol over time correlates with a shorter life span, the truth is scientists still don’t know if it actually causes health problems that lead life to end sooner, despite headlines suggesting otherwise.

This year there were two huge news blitzes following the publication of a pair of studies in the journal The Lancet, one published in April and one in August. The first proclaimed that drinking an extra glass of wine would take 30 minutes off your life, and the second—which was the third most-cited research paper of 2018—seemed to say there is no safe level of alcohol consumption. Technically, these headlines were accurate representations of the studies, both of which were massive in terms of sample size. The details, however, undermine these broader interpretations.

Here’s what we know for sure: On a cellular level, alcohol temporarily harms the body. The liver breaks down the majority of the alcohol we drink, creating acetaldehyde as a byproduct. The acetaldehyde, which is a carcinogenic, causes the liver to accumulate fat, says Doug Simonetto, a hepatologist at the Mayo Clinic. Inflammatory cells then flock to the excess fat, where they release substances that can cause liver cells to die.

The liver is a resilient organ and regenerates cells fairly quickly, similar to the way skin heals after a minor cut. However, if you don’t give your liver a break from drinking, the damage occurs faster than the liver can recover. Over time, that damage can lead to liver cancer, fatty liver, scarring of the liver, and liver failure, which can be fatal without a transplant. Drinking has been linked to diseases beyond the liver, including heart disease, and cancers including in the breast, colon, head, neck, and throat.

Here’s what we don’t know: the amount of drinking that actually reduces life expectancy as a result of any of these afflictions. In part, this is because there’s no good way to measure toxicity over time in humans. Ideally, researchers would conduct a randomized trial, where some people drank more than others over time, and then look at the health outcomes. However, because we already know alcohol is toxic, asking people to drink for science is unethical. (Although this hasn’t stopped the alcohol industry from trying to create studies of this sort—earlier this year, the New York Times found that liquor-company executives had donated money to a foundation that granted money to researchers at Harvard for a randomized controlled trial. The trial was shut down shortly after the investigation published.)

That means scientists have to rely on cohort studies, which observe people’s self-reported behavior over time. From a research standpoint, they’re hardly ideal. Most of us are really bad at estimating how much we drink; studies have found we’re likely to omit roughly half to three quarters of the amount we drink when responding to surveys about our consumption habits. But even if participants reported their drinking habits with 100% accuracy, there would still be the question of what other factors in their lives might have affected their health, like age, gender, occupation, or country of residence. Although studies try to account for some of these influences, it’s impossible to factor in every single difference between one person’s life and another’s.

All that said, these highly influential, survey-based cohort studies are the best current research has to offer. Considering more closely how they are conducted, and looking deeper into their methodologies, brings into sharp relief what we don’t know about alcohol and long-term health.

The individual sweet spot

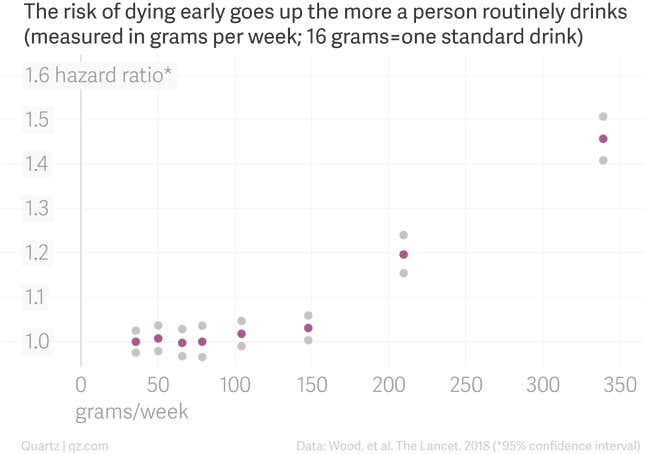

The first of the two recent high-profile studies, published in April, started with the assumption that a “standard drink” contains eight grams, or half a tablespoon, of pure alcohol. (The “standard drinks” used in government guidelines vary by country; in the UK, it’s eight grams of alcohol, but in the US it’s 14. In Austria, it’s a whopping 20 grams.) The team of researchers, led by University of Cambridge biostatistician Angela Wood, then took 83 standardized cohort studies that, combined, examined at least a year’s worth of drinking habits of almost 600,000 adults over the age of 40. This way, Wood’s team could get an idea of the average amount people were drinking over the course of their lifetimes. Next, they put these adults into eight groups, based on the amount that they reported drinking over time. The first four groups all drank, but in quantities of less than 100 grams per week. The latter four groups had increasingly heavy drinking habits; the final group included everyone who reported drinking over 350 grams per week.

Below is a reproduction of a chart of the results, which was published in the study and widely cited by the media. Each magenta dot represents the (estimated) average amount drank per week by participants in each of the eight categories. The grey dots above and below each magenta dot are the upper and lower bounds of a 95% “confidence interval,” a statistical tool used to show the range of uncertainty in an estimate. What it means is that if you took a sample exactly like this 20 times, 19 times (95% of the time) you’d get a result that fell within the range of the upper and lower bounds. It also uses hazard ratios to show how drinking habits are correlated with dying. In medical science, hazard ratios show “how often a particular event happens in one group compared to how often it happens in another group,” according to the National Cancer Institute’s definition.

If you find all that confusing, don’t worry. You’re not alone. Who measures their drinks in how many grams of pure alcohol they contain? And what does a 1.45 hazard ratio actually mean?

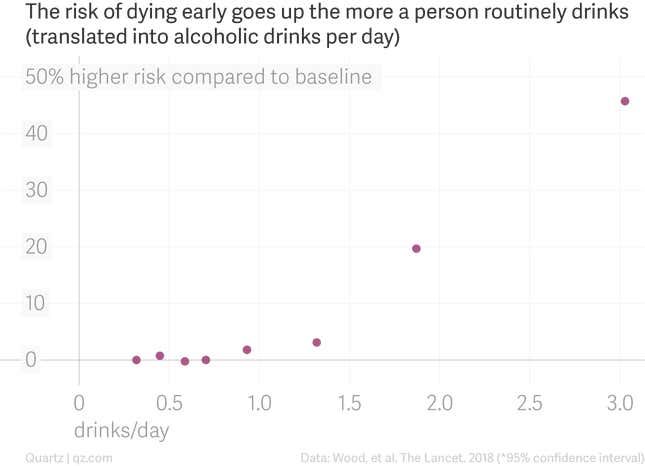

The first step to understanding this study is to translate these findings into measures that make sense to normal humans. So, instead of grams of pure alcohol per week, we’ll use drinks per day. A typical beer or glass of wine is about two units, or 16 grams of alcohol. And instead of hazard ratios, we’ll use a percentage that measures increased risk.

This helps. It suggests that the study found that, basically, if you had an identical twin who led exactly the same lifestyle as you, but had two drinks per day instead of one glass of wine with dinner like you do, your twin would be about 20% more likely to die at any moment after you both turn 40. Yikes, right?

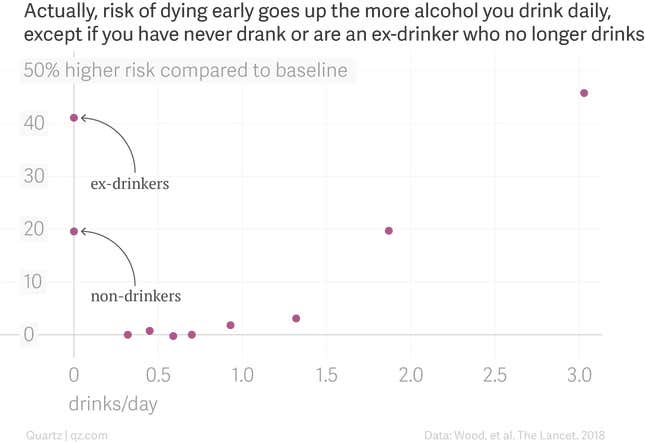

You’d think that to live the longest, you’d have to cut out drinking entirely. However, that leads us to another problem with the study: There’s actually no evidence that cutting drinking entirely is better than having one or two drinks per day. There were two types of study participants who didn’t get put into one of the eight previously mentioned groups: those who have never drank at all, and those who used to drink but quit entirely. And when you put those on the chart, it looks a lot different:

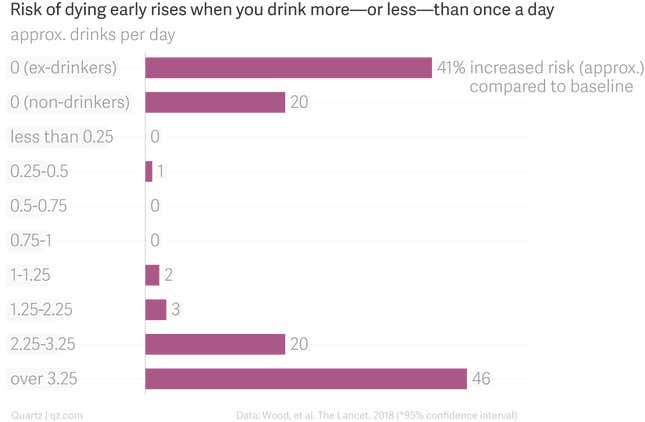

In part, that’s explainable because, more often than not, adult ex-drinkers or non-drinkers don’t drink for medical reasons. As Vox explained in April 2018, research has shown that people who never drank or who have quit drinking often make these choices because they are already extremely unwell, giving them a shorter life expectancy than the general population anyway. Below is a chart that best expresses the risks of drinking, and the risks for those who abstain.

Then there’s another factor to consider. “Twenty percent more likely to die” doesn’t mean a lot on its own, because the absolute risk of dying at the age of 40 is pretty low. You’d have about half your life ahead of you, assuming a life expectancy of 80 years.

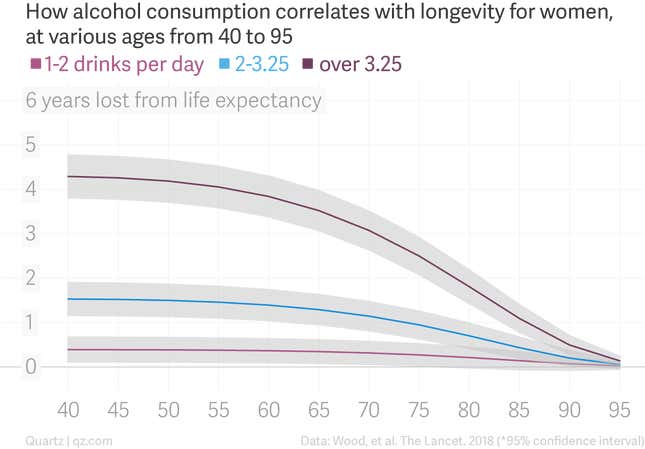

So, to help make the data more applicable, the researchers converted the numbers to show the potential loss of life expectancy based on current age. For example, based on their data, a 40-year-old man who has between one and two drinks a day lowers his life expectancy by about six months. Between 2 and 3.25 drinks a day, his life expectancy decreases by about two years, and upwards of 3.25 drinks per day, by five years.

But before you take these data as gospel, consider this: Each of these curves assumes that a person drinks around the same amount, every day, for their entire lives. “It’s unrealistic to assume people are not changing their drinking behavior over time,” says Dana Goin, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at the University of California-Berkeley. But it’s essentially impossible to track daily drinking behavior on that granular a level, with a sample size big enough to come to stronger conclusions.

Stricter guidelines for populations

The second study that made headlines this year, published in August, took a different approach. To start, it used 10 grams as a “standard drink.” Then, the team, led by researchers at the University of Washington’s Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, examined data from almost 700 studies that looked at drinking rates across 195 countries, along with alcohol sales, population, tourism numbers, and estimates of how much drinking was happening illegally in each country.

The researchers next compared approximations of nationwide drinking rates to the prevalence of 23 health outcomes from 592 cohort studies, including heart disease, cancers, and infectious diseases like tuberculosis and the common cold.

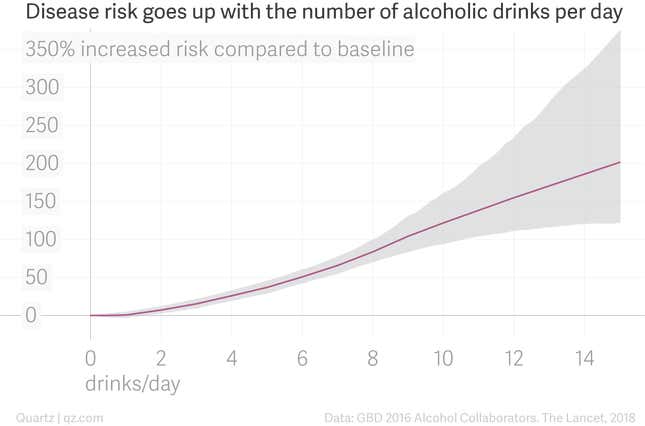

The study concluded that technically, if you had only one drink per day, the relative risk of developing any of the 23 health outcomes increased by 0.5% compared to someone who had nothing to drink. The risks quickly compound the more drinks a person has per day. The chart below shows the dramatic upward trajectory of this trend—though it appears far more dramatic when you look at the range between the upper and lower limits of the estimates (shown in gray, and also representing a 95% confidence interval), especially toward the higher-drinking end of the scale. The magenta line is the best estimate based on their statistical analysis.

Again, though, the absolute risks—particularly at low levels, like one or two drinks per day—are small. As David Spiegelhalter, a statistician at the University of Cambridge (who was not involved with Wood’s study), points out in a blog post, if 100,000 people had one drink every day for a year, 918 of them would develop one of those 23 conditions. If those same people didn’t drink, 914 of them would. A difference of four people.

As the number of drinks per day increases, the risks increase exponentially. If 100,000 people had two drinks per day for a year, 977 would develop one of the 23 conditions considered—so 59 more than at the one-drink-a-day level. If the same number of people had five drinks per day for a year, there would be an additional 275 on top of that: so 1,252 out of 100,000 people drinking at that rate would develop one of the 23 conditions. Notably, the uncertainty around these risks increases as the number of daily drinks do, too.

“One drink per day isn’t [much of] a risk for an individual,” says Max Griswold, the lead author of the paper. But health-policy makers need to consider what would happen if an entire country took on those risks. “If 100 million are drinking and 2% risk getting a disease they normally wouldn’t have gotten of them get a disease they normally wouldn’t have, we’re talking about 2 million [cases]” he says.

Currently, the US Centers for Disease Control advises men to cap it at two drinks per day, and women who aren’t pregnant at one. In the UK, the government recommendation is one drink (two units) per day for all genders. If governments were to heed this study, they’d revise those guidelines to reinforce that no level of drinking is completely risk-free.

So how much is too much?

The takeaway from these studies can be hard to pinpoint, but both seem to suggest that you can’t make daily decisions in a vacuum. You have to consider how much you drink regularly and how long you have been drinking that much—although cutting back some won’t hurt you.

There seem to be some increased health risks from drinking in any amount—especially beyond more than seven drinks per week. Excessive alcohol could very well be taking years off our lives. On a day-to-day basis, though, it’s impossible to say what it really means for your long-term health if you have an extra glass of wine with dinner, or multiple drinks at a party. The uncertainty here all comes down to the fact that there are no data clear enough to show at what point alcohol consumption becomes directly responsible for a shortened life span. Instead, all we have are correlations.

Put another way, we know that alcohol has risks. But, there are a lot of other routine behaviors that are risky, too. As Spiegelhalter writes, “there is no safe level of driving, but government[s] do not recommend that people avoid driving.” And, he points out, living itself comes with a 100% risk of death.