Google is a truly unusual place to work.

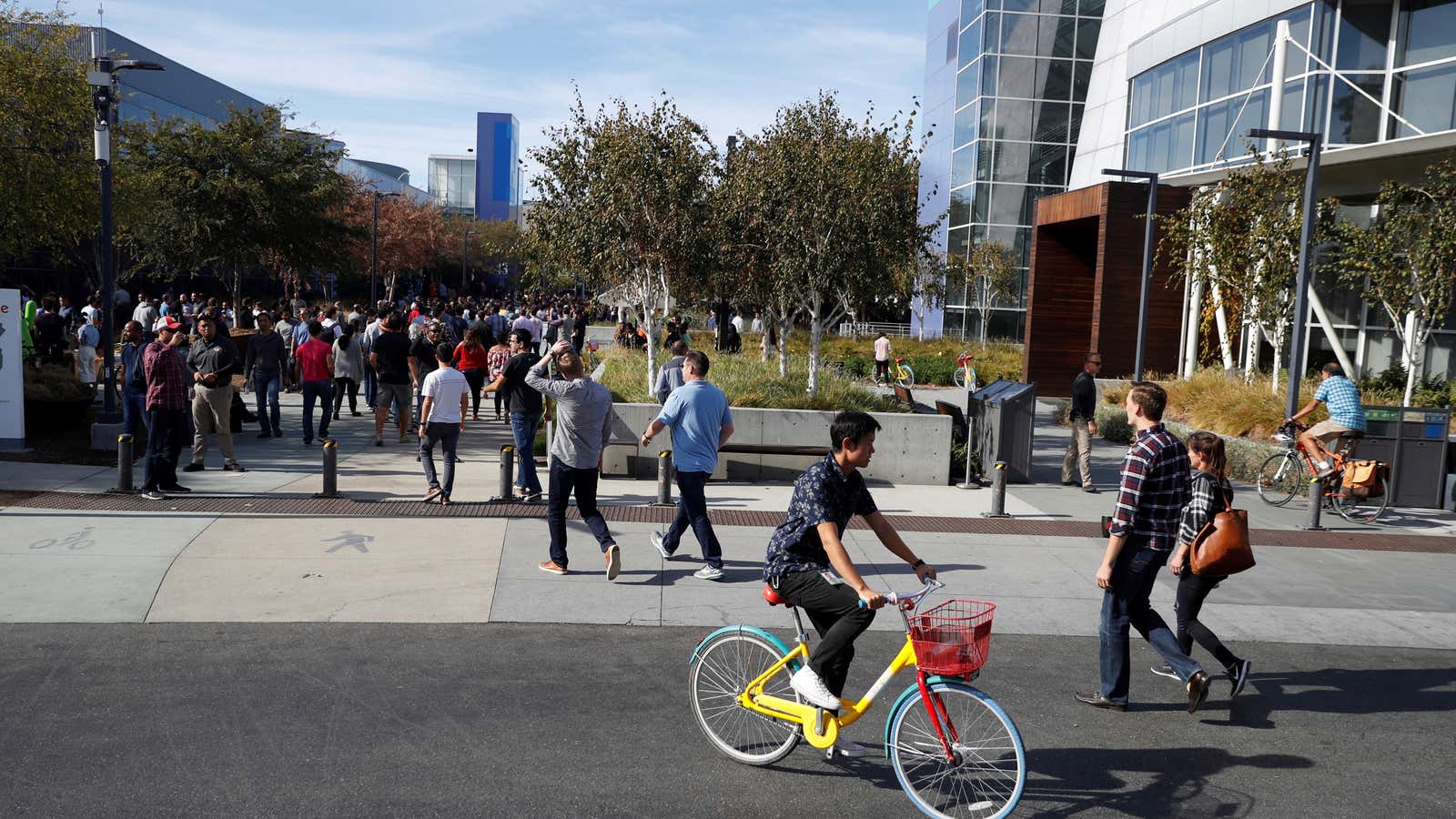

The campus in Mountain View is dotted with giant statues of sweets representing the company’s Android versions—Eclair, Donut, Gingerbread, Honeycomb, Ice Cream Sandwich, Marshmallow. Multicolored bikes, unlocked, line the racks outside the buildings, many of which have laundromats, gyms, photo booths, and other funny statues, plus offices with kitchens containing a dizzying array of snacks. There is free lunch (and breakfast, and minimal dinners, too).

On the surface, it all seems delightful. Certainly, I was excited when I got there on a contract as a document review attorney in 2013. But deeper engagement with the company revealed a surprising and widespread disgruntlement. At first I didn’t understand why everyone was so defensive, glum, and sullen at this otherworldly workplace. But I soon learned the reason came down to deep inequality.

Nearly half of Google workers worldwide are contractors, temps, and vendors (TVCs) and just slightly more than half are full-time employees (FTEs). An internal source, speaking anonymously to The Guardian, just revealed that of about 170,000 people who work at Google, 49.95%, are TVCs and 50.05% are FTEs. As The Guardian reported on Dec. 12, a nascent labor movement within the company led to the leak of a rather awkward document, entitled “The ABCs of TVCs,” which reveals just how seriously Google takes the employment distinctions.

The document explains, “Working with TVCs and Googlers is different. Our policies exist because TVC working arrangements can carry significant risks.” Ostensibly, TVCs are excluded from a lot of things because letting them in on the company’s inner doings threatens security. “The risks Google appears to be most concerned about include standard insider threats, like leaks of proprietary information,” The Guardian writes based on its review of the leaked document.

But in the case of the team I was on—made up of lawyers, most of whom were long-term contractors—we reviewed the most important internal documents and determined whether they were legally privileged. In other words, outsiders were deciding what mail and memos from top Google executives, engineers, and other deep insiders should be considered private in lawsuits and investigations. The irony of this bizarre access, in view of our disparate treatment, was not lost on us. And eventually, it wore workers down.

There was a two-year cap on contract extensions and a weird caste system that excluded us from meetings, certain cafeterias, the Google campus store, and much more. Most notably, contractors wore red badges that had to be visible at all times and signaled to everyone our lowly position in the system.

On days when the full-time employees were on retreats or at all-hands meetings, the office was staffed entirely by contractors. We’d nibble on snacks from the office kitchen, contemplate whether to go to the pool or gym or yoga or dance classes, and laugh amongst ourselves at this heavenly employment hell.

But it was also oddly depressing. We were at the world’s most enviable workplace, allegedly, but were repeatedly reminded that we would not be hired full-time and were not part of the club. Technically, we were employees of a legal staffing agency whose staff we’d never met. We didn’t get sick leave or vacation and earned considerably less than colleagues with the same qualifications who were doing the same work.

In time, I learned the patterns for each class of contractor hires. We came in groups on 12-week contracts that were then renewed, usually for six months, until we neared two years. As the two-year limit approached, the optimists in any given class cajoled and negotiated with managers, and the pessimists grew grumpy and frustrated about having to look for new work. Either way, the response was the same. All had to go.

A few months into my stint at Google, I dubbed my employee ID, “The Red Badge of Courage,” after the 19th-century war novel by Stephen Crane—because it was like walking around with a wound, only not one contractors could be proud of. As for the meetings we could attend—not the “all-hands” for Googlers—I jokingly called those “small hands.” Often, at these gatherings, we were warned by our managers about the tentative nature of our employment, as if we could forget.

The interesting thing about this tiered system is that it also impacted full-time employees negatively. The many distinctions made it awkward for the thoughtful ones to enjoy their perks without guilt, and turned the jerks into petty tyrants. It wasn’t an inspiring environment, despite the free food and quirky furniture—standing desks and wall plants and cozy chairs suspended in the air. And ultimately, this affected the work we all did. Even full-timers complained incessantly about the tyranny of this seemingly friendly tech giant.

We were all reasonably well-versed in labor law, having reviewed documents for Google suits, so contractors and employees alike were aware of why the company chose this dispiriting system. If distinctions between TVCs and FTEs aren’t sufficiently clear, the company might be accused of actually employing contractors and be liable for them.

Another bitter irony, then, is that regulations created to protect workers ultimately incentivize employers to not hire people, and to treat contractors unequally to ensure minimal confusion. And as explained in an anonymous letter from TVCs to CEO Sundar Pichai on Dec. 5, titled “Invisible no longer: Google’s shadow workforce speaks up,” the temporary workers tend to be from groups that have been historically excluded from opportunity in society at large and in the market. They explain:

The exclusion of TVCs from important communications and fair treatment is part of a system of institutional racism, sexism, and discrimination. TVCs are disproportionately people from marginalized groups who are treated as less deserving of compensation, opportunities, workplace protections, and respect.

The solution isn’t as simple at it may seem. For workers, turning down a Google contract means passing up an opportunity, albeit a flawed one. The minorities and women who make up much of the TVC workforce know that beggars can’t be choosers. An imperfect job beats none when you need an income. And TVCs who voice displeasure with anything are quickly shown the door without any of the same processes to protect them as employees, so lobbying from the inside—unless done en masse and anonymously, as happened last week—is ill-advised. Ultimately, if TVCs make it too uncomfortable for Google to hire them, they risk minimizing opportunities for those who need them most.

So, ideally, Google would take the high road. If it wants to “do the right thing,” as its motto goes, it can hire most workers full-time. But that’s admittedly costly in terms of administration, benefits, compensation, and potential liability. And what it’s doing isn’t unique—many Silicon Valley corporations rely on contractors for a bulk of their core work. Microsoft did this too, until it settled a massive class action lawsuit in 2000 with “permatemps” for $97 million.

Someday, perhaps Google will also end up paying out to those who work for less just to be at “the best” workplace in the world. For now, however, it seems that until labor laws change to reflect the current employment reality and incentivize full-time hiring, inequality will persist—even as the company appears sweet on the outside.

Looking for more in-depth coverage from Quartz? Become a member to read our premium content, and master your understanding of the global economy.