The civil war may have brought several of Syria’s economic sectors to a standstill, but the relentless fighting hasn’t yet closed the country’s largest unregulated market: foreign exchange.

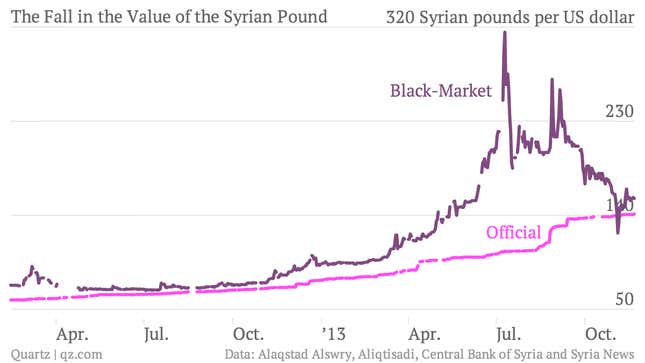

It’s inherently difficult to calculate the unofficial rate of any currency (much less during a civil war), but multiple reports this month have confirmed that the Syrian pound’s black market price has made an unprecedented leap against the dollar, trading at essentially the same “official rate” as set by the Syrian Central Bank. When you compare the difference between these two rates to what it was just a few months ago, the recovery is staggering.

Gaping differences between official and unofficial rates are not uncommon for war-torn economies. Fragile governments often overvalue official exchange rates to manage inflation, whereas black marketers can fetch higher domestic prices for “hard currencies” like dollars, due to the increased demand for foreign monies.

Syria has been no exception to this phenomenon. Since the start of the civil war in early 2011, the pound has plummeted on the black market, while inflation rates have soared.

To put this in perspective, prior to the start of the protests against President Bashar al-Assad, the pound traded at 47 to the dollar. Almost two-and-a-half years later, it hit an all-time low in July 2013, trading at 300 to the dollar (versus an official exchange rate of roughly 110 to the dollar). Official reports have pegged Syria’s inflation rate at hyperinflation levels of over 50%, while other estimates are in the hundreds.

So what explains the pound’s recent convergence with the official rate? An anonymous currency dealer told Reuters earlier this month that “the dollar was brought down by the security apparatus’ iron-fisted measures,” stating that he knew of several exchange rate firms in Damascus that were raided and shut down in the recent weeks.

The Syrian government has taken a hard-line approach in regulating currency exchangers in an effort to close the gap between the official rate and the black market rate. This past June, Syria’s Ministry of Economy and Trade required licensed private sector importers to find their own source of financing to buy foreign currencies, and just one month later, the government passed a legal amendment that sentences anyone practicing currency exchange without a license to 3-10 years in prison and a fine of at least 5 million Syrian pounds, or roughly $35,400.

These capital controls may have had some success in reigning in the black market rate, but Steven Hanke, a Johns Hopkins professor and head of Cato Institute’s Troubled Currencies Project says that the regulations are not the driving factor behind the pound’s comeback.

“The big story in Syria is about expectations. Expectations in Syria were never good, but they are less bad than they were,” says Hanke.

Hanke notes that capital controls and policing black markets are common “window dressing” techniques in civil war situations, and even if they are “the letter of law” in some government-controlled areas, it is unlikely that they are being enforced strictly enough to affect black market prices to this magnitude.

After facing setbacks earlier in the war, Assad forces have been on the offensive in the recent weeks. The preconditions for a peace settlement between the regime and opposition forces has markedly shifted from demanding that Assad step down immediately, to the possibility of opposition forces accepting a political transition plan that includes President Assad in the short to medium term.

Rabie Naser, co-founder of the Syrian Center for Policy Research said in a phone interview from Damascus that with the strengthening of the regime’s military operations, Syrians are more hopeful that the economy will come back to life. As Assad’s regime gains more ground, Naser says, “It gives an expectation of a stronger economy in the near future.” He points to the fact that there are already a number of manufacturers reopening business in Syria, particularly in Homs.