American monolith retailer Walmart announced that Doug McMillon would become just the fifth CEO in its 62-year history this morning. Like his four predecessors, McMillon is a white, heartland-educated American male—an Arkansas native, who began his career in a Walmart distribution center in 1984.

Since then he has followed almost exactly the same path to the top job as outgoing CEO Mike Duke did. Since 2009 he’s headed Walmart’s international operations; before that he spent three years running Sam’s Club, Walmart’s membership-based wholesale business. Clearly, McMillon was being groomed for the CEO slot. Yet today the company is facing challenges its founder, Sam Walton, could never have anticipated.

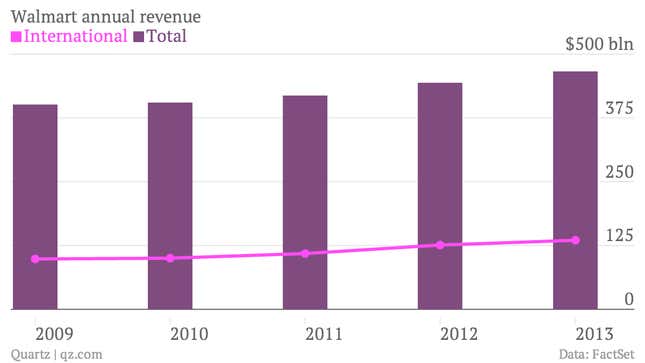

McMillon managed to grow Walmart’s international business, both in absolute terms, and as a percentage of the company (from 25% of total revenue in 2009 to 29% by 2013). But Walmart’s troubled Indian expansion has hit a roadblock, its operations in Mexico have been beset by bribery allegations, and questions remain about the viability of its low–cost business model in the fiercely competitive but highly attractive Chinese market.

Meanwhile, at home, the company has been bombarded with criticism over the paltry wages it awards its US workers, and the fact that many of its itinerant workers do not work enough hours to qualify for benefits, including healthcare. Last week, CNN Money reported that one Walmart store in Ohio was collecting food donations for “associates” (i.e. employees) who couldn’t afford a Thanksgiving dinner. (Walmart responded that such food drives are only for workers facing unexpected hardships like illness.)

Walmart’s business model is built on enormous volumes and tiny profit margins (its net income margin was just 3.62% last year). There is a persuasive argument that higher wages and benefits for its 1.4 million US workers would be its undoing—and thus deprive its millions of poorer customers of access to cheap goods. But that argument isn’t likely to relieve the pressure on the company, which comes at a time of intense competition from online retailing behemoth Amazon.

Conventional wisdom suggests that internal CEO candidates generally deliver better returns for shareholders than external ones do. However, that’s not always the case for underperforming companies. Walmart’s share price might be near record highs, but the stock has lagged the S&P 500 this year, and over 2, 5 and 10 year timeframes.

Among the most dangerous myths in succession planning, according to the Stanford Graduate School of Business, are beliefs that what worked in the past will work in the future, and that when a company has a great internal candidate, it doesn’t need to look outside. Walmart’s board of directors obviously disagrees.

There’s little doubt the company’s founder would have approved of the choice; in fact McMillon’s close links (paywall) to the Walton family, Walmart’s majority shareholders, were probably a factor in him getting the job. He certainly would have been a perfect fit 20 years ago, when the company’s international operations were still embryonic, the internet didn’t pose much of a threat to brick-and-mortar retailers, and Walmart was being feted rather than criticized. But today a fresh set of eyes might have been better.