It’s never been easier to get customized DNA to code for anything you like. All you need is a simple translation method and a little money.

For example, Adrien Locatelli, a high-school student in Grenoble, France, recently downloaded parts of the Bible and Qur’an, translated the text into DNA, and then injected it into his thighs. On Dec. 3, he published a write-up of the self experiment on Open Science Framework, a site where researchers upload non-peer-reviewed drafts of their work for others to assess.

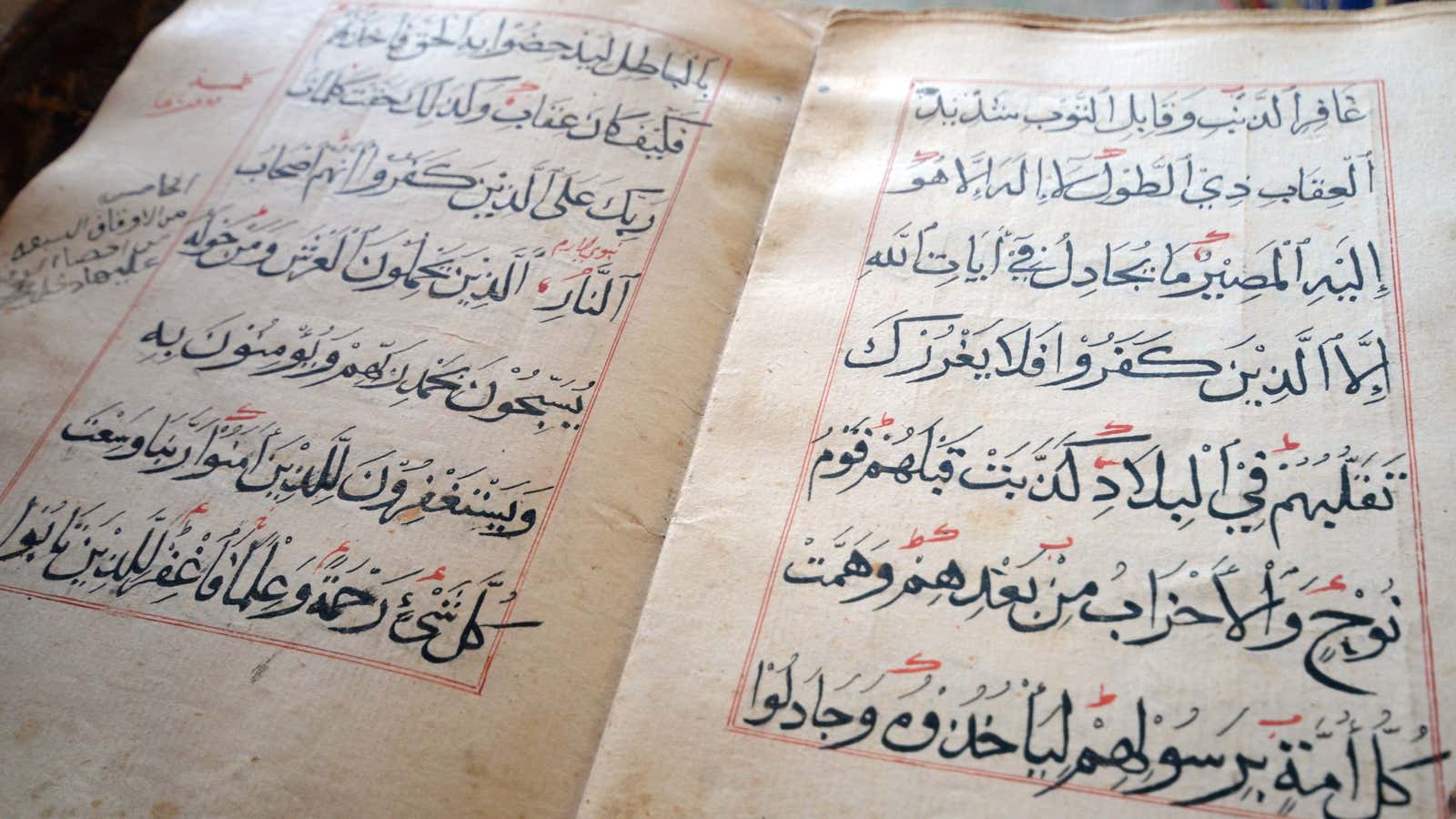

Logistically, it was easy. Locatelli first translated the text into the nucleic acids that make up DNA, using a rudimentary system: For the Bible’s book of Genesis, he converted the 22 Hebrew letters into one of four possible acids—cytosine, thymine, guanine, or adenine. Cytosine and thymine stood for five letters each, and guanine and adenine stood for six letters each. For the Arabic text, Locatelli eliminated all but five out of 28 letters, and gave three of them unique nucleic acids and allowed Ra and Sad to share thymine. In both cases, Locatelli ignored spaces, punctuation, and diacritical marks.

Then, he purchased custom strands of DNA, as well as benign viruses that are used to insert new DNA into cells, from the companies VectorBuilder and ProteoGenix, respectively. He bought some saline and syringes and was off to the races. He suffered only a minor allergic reaction after the injection.

“I did this experiment for the symbol of peace between religions and science,” Locatelli told Live Science. (He notes in his paper that the work may “not have much interest.”)

Sriram Kosuri, a biochemist at the University of California-Los Angeles, told Live Science that he couldn’t be sure Locatelli’s methods actually worked; there’s no way to assess whether the viral vector successfully brought the synthesized DNA into Locatelli’s cells.

But the teen’s work does show just how easy it is to store any kind of information in DNA. It’s also an incredibly efficient form of storage, which is why scientists have been eying it as a way to safely store massive amounts of data in compact spaces. So far, it’s been prohibitively expensive to create synthetic DNA for data storage, although biotech companies are racing to find ways to do it more cheaply.

The goal with commercial storage, of course, is to be able to translate it back into usable information. Theoretically, if the new DNA had been inserted into Locatelli’s cells properly to the point where they would replicate like his own DNA—meaning that he genetically edited himself—the text-based DNA could be translated back text. However, that probably didn’t happen; the most advanced medical research has just started to develop gene therapies. And even if the synthetic DNA was preserved, the initial translation was so imprecise it’d be difficult to recreate actual texts.

“I think that for a religious person it can be good to inject himself his religious text,” Locatelli said, although he did not elaborate on why he felt this way. He also hasn’t indicated whether or not he believes in any particular faith.