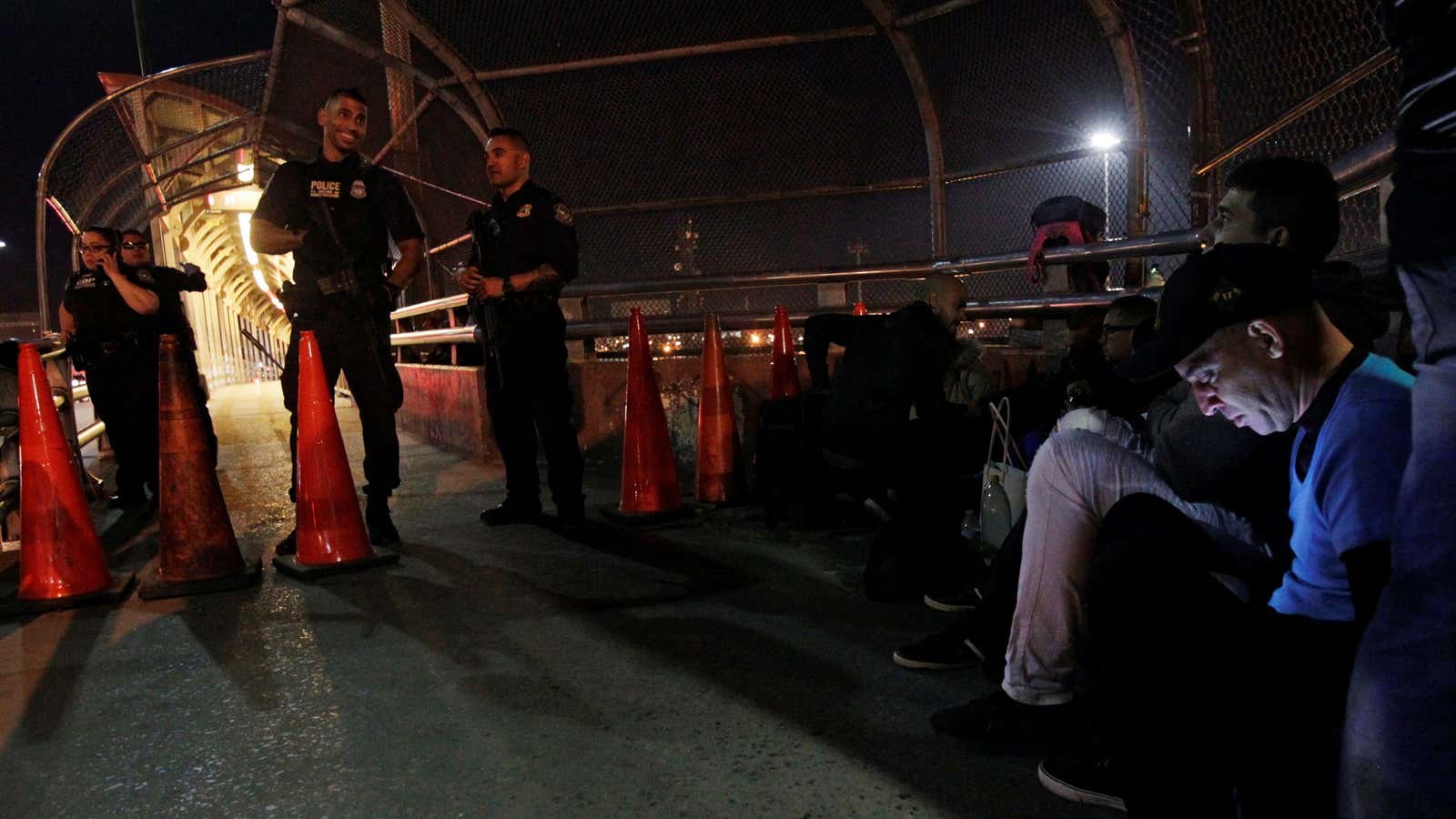

Immigration was one of 2018’s most politically explosive issues, whether in the US, Germany, or Turkey.

Ahead of next year’s continuing battle, researchers from the University of Washington are offering some handy figures in a new paper: There are at least 75% more immigrants than previously thought. And about a third of them are going back home.

The findings, published Dec. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are based on an alternate method of counting immigrants. It includes people moving out of their countries, as traditional statistics do, and also those returning home.

The new data offer a more nuanced picture of migration flows—and the kind of policies needed to handle it.

Immigrants leaving home

The researchers looked at immigration flows over five-year periods since 1990, using estimates put together by the UN as well as other sources. Throughout that period, the proportion of people on the move has stayed roughly the same: between 1.13% and 1.29% of the global population, according to the authors’ analysis.

The data also show that traditional methods have vastly undercounted the number of immigrants. While commonly accepted estimates put global migration at up to 46 million every five years between 1990 and 2015, that number is between 67 million to 87 million, depending on the time period, the new study says.

For example, the number of Mexican immigrants settling in the US is more than double than common estimates. Take a look below at how the two sets of figures compare for other migration flows from 2010 to 2015:

Returning migrants

The higher number of incoming immigrants identified by the new paper are offset by those who are going back to their country of origin. Here are the biggest flows of immigrants heading home between 2010 and 2015, according to the paper:

The data are as good as the UN estimates they are based on, the authors say. And immigration statistics have been traditionally spotty. Still, their alternative method sheds light on migrants’ back-and-forth movement, which is not usually recorded officially.

This kind of information should make public officials’ jobs easier. Immigration politics aside, communities on the receiving end of immigration have to provide everyday services for newcomers. “You need everything from medical infrastructure and trained personnel to elementary schools,” points out University of Washington professor Adrian Raftery, one of the authors.