We know about the pay gap for women. Perhaps what we should be talking about the one for married men.

Economist Guillaume Vandenbroucke turned his attention to the very, very well-studied subject of the gender pay gap and realized the conventional wisdom may be wrong.

The gap has been quite persistent over time, although it is improving. In the US, full-time working women earn 80.5% of what men earned in 2016, about 1% more than the previous year, according to the US Census Bureau. Controlling for age, experience, occupation, and industry, researchers say the gap narrows even further: closer to 91%.

The conventional explanation for why the pay gap exists is that many women cut back on work or leave the workforce altogether to raise and care for children. This depresses future earnings as they miss promotions, professional development, and other benefits open to most men.

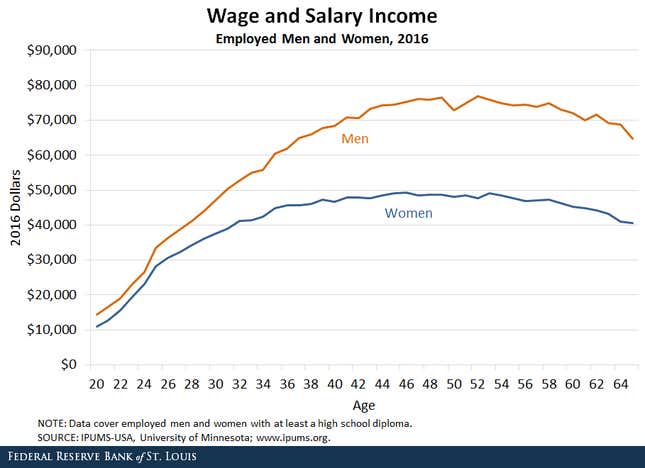

It seemed to match the data. Earnings of women and men track each other quite closely until around age 26. Then the gap grows significantly. Women at age 45 are making about $50,000 compared to more than $75,000 for men. This suggested women were leaving the workforce to have children.

Yet Vandenbroucke found much of the wage discrepancy was not correlated with gender, but with men’s marital status. For employees with at least a high-school degree, single men and single women had “very little, if any, difference” in wages over their lifetime. This data does not seem to support the idea that caring for children is the primary factor responsible for women’s pay gap relative to men. While married women are likely to have more children than single women, there was no pay gap between the two groups. Ultimately, married men earn an average of almost $90,000 by their mid-40s, almost double the average of other cohorts.

Does that mean getting married will increase a man’s wage? Probably not, but we don’t know. It could be that men with higher wages are more likely to marry, warns Vandenbroucke, and other factors could be at work.

“The gender wage gap remains a complicated topic,” he writes. “But progress may come from asking different questions.”