When General Motors announced last month that it was shutting down small-car production and mothballing its Lordstown Assembly plant outside of Youngstown, in northeast Ohio, the news felt inevitable. While GM once built nine of every 20 new cars sold in America between 1950 and 1980, its market dominance has long since faded. Along with the other two of Detroit’s “Big Three” automakers, GM has been slashing shifts and shuttering factories for decades, gutting cities like Youngstown across America.

But nothing that led to the layoff of Lordstown’s 1,500 workers was inevitable—not GM’s failure, not the triumph of foreign small cars, and not even the withering of Detroit’s industrial might—provided you know where to look. Nearly a half-century ago, as the first gusts of global competition began buffeting the US economy, an iconic strike in Lordstown presented GM with an alternative path—and incited the rest of America to rethink our relationship to work.

In the late winter of 1972, Lordstown workers rebelled against GM’s experiment with a bold new management style that put a premium on automation while treating assemblers as though they were little whirring parts of one giant machine. Their uprising became a national symbol of blue-collar disaffection. “Lordstown syndrome,” as the media dubbed it, was fueled by the idea that, for American society to thrive, people needed work, yes, but more specifically, meaningful work—a purpose that went beyond the simple act of fastening a spring to a Chevrolet’s left rear axle. In the national debate that ensued, America pondered how a society that neglected to treat work holistically would hurt the competitiveness of its workers, and, ultimately, the health of its communities.

That 1972 strike—or, more precisely, GM’s response to it—marked the beginning of the company’s long but uneven descent, which would be characterized by a repeated impulse to bet on fancy, futuristic but unproven technologies while undervaluing its workers. And so, long before GM CEO Mary Barra’s announcement in late November, we’ve known how the story of GM ends. But Lordstown’s strange moment in 1972 teaches us about what could have been written instead.

The factory of the future

The year was 1970. General Motors was the biggest company on the planet, with revenue of $22.8 billion ($152 billion in today’s dollars). It had just dazzled the world with its unveiling of Lordstown Assembly, featuring an intensely mechanized assembly line, computerized quality control, and its pièce de résistance: 26 robots that zipped around chassis like praying mantises on crank, fusing together the steel sheets that became the car’s body. The most automated factory the industry had ever seen, the plant was a revolution in manufacturing efficiency—”an industrial engineer’s dream,” according to John Russo, who worked in the late 1960s at a GM plant in Michigan and went on to become a labor relations scholar and director of Youngstown State University’s Center for Working-Class Studies.

Just as remarkable as the phalanxes of robots was the workforce that GM picked to sweat alongside them. “The labor force—long-haired, pigtailed and bell-bottomed—is the youngest of any GM plant,” a Feb. 1972 Time magazine article (paywall) declared. Indeed, the average age of Lordstown’s 8,000-plus assemblers was 24. They were also the best educated and most ethnically diverse workforce in the industry’s history, says Russo. Many had fought in Vietnam.

Why the radical change? Foreign competition—what had once seemed no more than an irritant to a company of GM’s market dominance—was swiftly solidifying into a small but real threat.

The company that bestrode the world

It was through the Model T that car ownership first came to the American masses, as Henry Ford’s mass production made an otherwise luxury item suddenly affordable. But the company that turned car ownership into a core American cultural institution was his company’s rival, General Motors. While Ford made the same boxy car, in the same drab black, for everyone, GM pioneered the modern concepts of branding and mass marketing. Each of its brands had a distinct look, price, and consumer base—or in the words of Alfred Sloan, Jr., the industry visionary who led GM in the decades before World War II, “a car for every purse and purpose.”

By the 1950s, GM marketing had penetrated the collective American psyche so thoroughly that its five iconic marquees were symbols of the country’s emerging class and cultural affinities. Old money rode in Cadillacs, explains economist Robert Gordon in his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, while the country’s managerial ranks drove Buicks. “Farther down the perceived chain of status were the Oldsmobile, the Pontiac, and the ubiquitous Chevrolet, America’s best-selling car year after year, eagerly bought by the new unionized working class that, in its transition to solid middle-class status, could afford to equip its suburban subdivision house with at least one car, and often two,” he writes.

The key to the cars’ appeal, and the company’s profitability, was GM’s knack for innovation—its ability to constantly churn out new ways of making its cars flashier, comfier, more fun to drive.

Many of these breakthroughs were practical: self-starting engines (as opposed to manual cranks), in-car air conditioning, automatic transmission, and power steering. But design was critical too. The pace of innovation was such that, by the late 1950s, every new model that GM turned out looked markedly different from its predecessor.

“Having passed Ford in the 1920s by offering cars that were changed every year, GM made sure it remained the styling and technology leader,” wrote Alex Taylor III, a longtime industry reporter for Fortune, in Sixty to Zero: An Inside Look at the Collapse of General Motors—and the Detroit Auto Industry. “Its cars of the 1950s were all new, their styling capturing the pent-up wartime desire for change with an exciting spirit bordering on the flamboyant: two-tone color schemes, outrageous fins, and high-compression V-8 engines.”

The distinctiveness of GM’s brands owed a lot to the fact that they operated as independent divisions. This meant Chevy engineers competed not just against Ford and Chrysler, but also against Pontiac and Oldsmobile to define the cutting edge of power, comfort, and style. What its brands did share, however, was that their cars kept getting longer and more jam-packed with profitable new features—and, therefore, heavier too.

Constant upgrades of style and quality were commercially critical because GM faced a challenge similar to the one Apple confronts today with its iPhone: a well-saturated market. By 1970, 29% of US families owned more than one car, compared with just 7% two decades earlier, according to economic historian Emma Rothschild in Paradise Lost, her 1973 book on Lordstown Assembly. American consumers had enough cars to get around. To keep them buying new ones, they had to be convinced—and with its steady stream of must-have new models, GM had perfected how.

These feats of ingenuity made GM the first company in history to earn more than $1 billion, which it did in 1956. Throughout that decade and the next, it was the planet’s most profitable company. GM’s dominion over the US auto market was unquestionably utter. Every year but two between 1950 and 1970, Americans shelled out more on new GM cars than they did Fords and Chryslers combined.

From this commanding perch, it was easy to dismiss competition. At first, anyway.

Foreign invasion

Germany’s Volkswagen introduced America to the Beetle in 1949. It sold exactly two.

Within a decade, those fortunes had improved considerably. The stubby cars that Volkswagen and other European carmakers specialized in had found a market among Americans who couldn’t afford Detroit’s pricey steel behemoths. Soon Japanese cars—Toyota debuted the Corona in 1965, rolling out the Corolla the next year—began appearing on streets of America’s west coast cities. In addition to sticker price, foreign cars also tended to be cheaper in the long run. Smaller and lighter than US models, they traveled farther per each gallon of gas. Their reliability translated into lower repair costs too. Word of this reputation spread. In 1963, a mere 5% of the cars bought in the US were foreign-made. That share had leapt to 13% by 1967.

GM, evidently, had had enough of the upstarts. “Annoyed by the popularity of the Volkswagen Beetle, GM’s brass decided in the late 1960s that it was time for the General to remind the pipsqueaks who was boss,” writes veteran auto market reporter Paul Ingrassia in his book Comeback: The Fall & Rise of the American Automobile Industry.

In 1968, GM announced that it was launching its first subcompact car, throwing down the gauntlet.

The “import-killer” from Lordstown

If the company had any doubts it would prevail over the Bugs and Corollas teeming on US highways, it didn’t show it. GM proclaimed that its new car would weigh less than 2,000 pounds and cost $1,800, the same as a Beetle, while featuring GM’s signature innovation.

To produce what the industry expected to be the world’s superior small car, GM picked its crown jewel factory, spending around $100 million to outfit the plant with the cutting-edge robots, automated line, and computerized quality control systems for which it became known. Lordstown Assembly would be the only US plant to make GM’s new “import-killer” subcompact, which it christened the Chevrolet Vega.

The hype was tremendous. In May 1970, GM rolled out ads saying nothing except two words: “You’ll see.” When the Vega finally hit dealerships four months later, GM had once again defied expectations. But for the first time ever, not in a good way.

The Vega looked plenty spiffy—certainly way sleeker than the dwarfish forms favored by foreign carmakers. But it was also nearly 400 pounds heftier and $300 more expensive than promised. And the disappointments didn’t end there. Features that were supposed to make it lighter, boosting gas mileage, left it prone to oil leaks. “Chevy dealers replaced so many Vega engines that they joked that the engines were ‘disposable,'” notes Ingrassia in Crash Course: The American Automobile Industry’s Road to Bankruptcy and Bailout-and Beyond. Its exterior tended to rust prematurely and buckle under pressure. On top of that, shortly after Vega production began, the labor union United Automobile Workers staged a 67-day national strike against GM, leaving the new car in short supply at dealerships.

The awakening should have been a rude one. It was GM’s first high-profile failure—a result of blundering labor management, sure, but also half-baked engineering and patchy quality control. The company could have regrouped and brought the Vega up to its usual snuff. But firm in its faith that Lordstown Assembly’s state-of-the-art automation ensured quality—and the production volume necessary to make a low-margin subcompact profitable—GM doubled down.

First, it laid off hundreds of Lordstown workers—reports vary, but put the number somewhere between 350 and 700. Then GM sloughed the extra work off on those who remained. Many of those axed worked on quality control. And to compensate for production lost to the 1970 strike, GM cranked up the assembly line’s pace. Those choices would have major repercussions for the way the Lordstown workers felt about their jobs, and ultimately, for the way American consumers felt about GM.

Life on the assembly line

Kenneth Picklesimer, now 72, started working at Lordstown in 1967, shortly after it opened. His first job was affixing carpets to the chassis of Chevy Impalas as their steely skeletons lurched past him down the line. When each new car appeared, the workers would scramble to add parts and adjustments before 60 seconds were up and the line whisked the car to the next station.

In the early 1970s, his job was to install a coiled spring to the rear axle, bolting it in place with a gun, his arms suspended in the same position for most of his 11-hour day. The spring weighed 10 pounds; fumbling it was known to snap fingers and shatter wrists. But that was nothing compared to the job worked by the guy in front of him, who was responsible for bolting the axle to the car’s body with a 40-pound airgun. “When it torqued up,” says Picklesimer, “it had so much kick to it that it’d take you off your feet almost.”

In addition to the physical strain, assembly work was a fraught combination of being agonizingly tedious while also requiring unflagging focus, says Tim O’Hara, 59, who recently retired from Lordstown after having worked there for 41 years. The pressure was immense.

“We had a lot of people that were hired and quit the same day ’cause they couldn’t take the mental impact, like being tied to one spot, you can’t go to bathroom unless someone comes to replace you,” says O’Hara, who is currently vice president of United Auto Workers Local 1112. “Everything’s regimented. You have to be mentally able to take it, and not everyone was.”

When Picklesimer started at Lordstown, he worked for Chevy. But in 1971, that ended, thanks to the creation of a final incendiary element in this already combustible situation: General Motors Assembly Division—or as the workers called it, GMAD.

The gestapo of GM

Up to this point, GM’s five brands—Chevy, Buick, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and Cadillac—operated distinctly, allowing give-and-take coordination between engineers and plant managers over part design and how to organize assembly, and, via dealerships, a direct feedback channel to loyal customers.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, GM severed those links when it thrust control over its factories under a single centralized authority, GMAD. By 1972, around 93,000 workers all around the country, and about three-quarters of GM’s production, had been absorbed into the division’s control, according to an April 1972 article in the New York Times.

GMAD embodied GM’s new strategy of centralizing and automating in order to up output and slash costs. And its head, Joseph Godfrey, embodied GMAD. The crewcut-sporting son of a former GM president, Godfrey was everything the Lordstown shop floor hippies weren’t. He spent his days poring over computer printout sheets and had a ruthless focus on the big picture.

“We have to compete with the foreigner,” Godfrey told the New York Times. The way to do that, he said, was to cut costs. And the key to that was technology—Lordstown’s robot welders, high-tech assembly line, and a new suite of computer systems that monitored output and quality.

How did workers fit into this vision? To Godfrey, their contribution could be reduced to a simple calculation of how much activity could be wrung from them. “Within reason and without endangering their health,” he said, “if we can occupy a man for 60 minutes [per paid hour], we’ve got that right.”

How? Line speed, for one. At Lordstown’s usual pace of 60 cars an hour, assembly line work was hard, but doable. In fact, GM could quite reasonably have squeezed out a few more cars per hour by upping the line speed to a pace of 65 or even possibly 70. Instead, management cranked up the pace to a dizzying speed of 100 cars an hour. “It deemed these moves to be reasonable because the Lordstown lines had been designed to build up to 140 cars an hour,” writes Ingrassia in Crash Course.

In other words, Godfrey’s plan wasn’t to boost productivity by making it easier for workers to do more, faster. Instead, it was simply to force them to do so. This was unheard of, then and now, says O’Hara. “We’re the only plant in the whole world, in the whole history of auto manufacturing, that ever did 100 an hour.”

The line speed-up meant assemblers had to cram the same work they used to do in 60 seconds into a mere 36 seconds. To keep workers in sync with that frenetic pace, the higher-ups instituted new rigid disciplinary measures, explains Russo, stepping up harassment and threats.

“GMAD was known as a kind of gestapo, no-holds-barred, ‘if you don’t like it get out of here’ approach,” he says. (In addition to studying Lordstown labor history, Russo has some firsthand experience with GMAD’s methods, having worked at a Michigan Oldsmobile plant during the division’s reign of terror. He recalls the foreman telling him, ‘Shut up, college boy and do your job,” when he suggested ways of improving workflow.)

Many of GMAD tactics seemed shortsighted—and sometimes downright petty. Employees who flagged flawed parts got a chewing-out from supervisors, even though cutting corners on quality would wind up raising warranty expenses, eating into profit. Foremen forbade the widespread practice among Lordstown workers of covering for each other on the line so that everyone could take breaks, says Kenneth Picklesimer. “Managers just started being real jerks,” he says.

As it happens, many of the 700 or so workers GMAD had laid off in its cost-cutting crusade were quality-control inspectors made redundant by the spiffy new computer systems and advanced automation that left little room for human error.

That’s what GMAD assumed, anyway. But the new technology was untested. And even the most draconian supervision couldn’t change the fact that, as Ingrassia notes, the Vega was too complicated to be assembled at warp speed.

GM was about to find this out the hard way.

Guerrilla war on the factory floor

At first, the story goes, Vegas started rolling off the assembly line with their seats slashed, windshields cracked, ignition keys jammed in locks, or other seemingly intentional flaws. As Time magazine reported in February 1972, the sheer volume of defective cars soon caused a backup in Lordstown’s overflow lots. With no room left to hold finished Vegas, managers had to do the unthinkable: Stop the assembly line. GM suffered around $40 million in lost output, according to Time.

Lordstown workers were mounting a guerrilla assault on the world’s most powerful company, and the media couldn’t get enough of it. The apparent acts of Vega vandalism proved an irresistibly dramatic enactment of a new source of anxiety gripping the American public in the early 1970s: absenteeism, turnover, worker delinquency, and general disaffection popularly known as “blue collar blues.”

However, despite press reports at the time, it’s not at all clear whether the bulk of the Vega defects were deliberate.

“The line was too fast and workers didn’t have enough time, so they’d just leave their parts in the front seat. That became a symbol of industrial sabotage, but in reality it was just a response to the speed of the line,” says Russo. “I’m not saying some people didn’t say ‘to hell with it’ [and vandalize a car]. But the reason originally was that the line was going too fast.”

That’s in keeping with what Picklesimer remembers.

“I did hear from reliable sources that a couple of people damaged a few vehicles because they were angry but I don’t think it was to the extent that the company was saying,” he says. His experience supported the much more mundane explanation: The assembly line was moving too fast for people to finish their work, and quality control staff had been laid off.

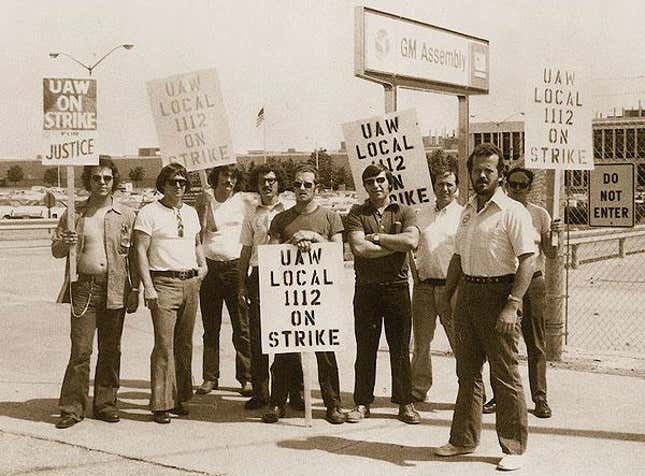

Whatever the case, GMAD fought back. Managers piled on mandatory overtime, while also stepping up arbitrary harassment and disciplinary firings. In March 1972, around five months after GMAD took over, Lordstown workers voted to strike.

Lordstown syndrome

This was no ordinary strike. Money wasn’t the issue. At about $4.50 an hour ($28.50 in today’s dollars), not counting $2.50 in fringe benefits, the Lordstown wage was about 25% higher than the prevailing average hourly wage nationwide. But as Gary Bryner, the 29-year-old head of the local UAW during the strike, put it, employees’ attitudes toward their jobs were about more than pay.

“The almighty dollar is not the only thing in my estimation,” said Bryner, as recounted in Studs Terkel’s 1974 book Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do. “There’s more to it—how I’m treated. What I have to say about what I do, how I do it.”

The main things the union wanted were for GM to rehire laid-off workers and return to the more flexible pre-GMAD work rules. But workers’ frustrations were broader than what the union was designed to address. For many, the problem was the monotony of their jobs—the brain-scalding tedium and physical strain that came from having to repeat a single task for 11 hours straight.

“[Despite GM’s robots] there’s some thinking about assembling cars. There still has to be human beings. If the guys didn’t stand up and fight, they’d become robots too,” Bryner said in Working. The increased speed of the assembly line further encroached on workers’ ability to feel fully human. “Thirty-five, thirty-six seconds to do your job—that includes the walking, the picking up of the parts, the assembly. Go to the next job, with never a letup, never a second to stand and think. The guys at our plant fought like hell to keep that right.”

For his part, Godfrey dismissed this concern, telling Automotive News that “it seems to me that we have our biggest problems when we disturb that ‘monotony.’” He continued: “The workers may complain about monotony, but years spent in the factories leads me to believe that they like to do their job automatically. If you interject new things, you spoil the rhythm of the job and work gets fouled up.”

But it was indeed newness and challenge that Lordstown workers craved. For instance, they regarded Swedish auto plants, where workers performed a range of tasks and mastered various skills, as a “distant industrial nirvana,” as historian Jefferson Cowie recounts in Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. Other Lordstown workers waxed longingly about how Japanese auto workers were allowed to play ping-pong during their breaks, according to Rothschild’s Paradise Lost.

Would prior generations of factory workers have suffered the GMAD tyranny in silence? Probably. Blue-collar workers of yore were far better acquainted with joblessness and deprivation, not least during the Great Depression. Their children and grandchildren, however, came of age in an era of plenty.

With their beards, beads, and Afros, the Lordstown workers believed in self-respect and self-expression. Coming of age during the civil rights movement of the late 1960s and the rise of anti-war activism, many distrusted authority and were comfortable with militancy. “They smoked dope, socialized inter-racially, and dreamed of a world in which work had some meaning,” wrote Cowie. Bryner signed off official phone calls with “Peace.” Indeed, the prominence of vets at the plant undoubtedly influenced many workers’ views. Russo recalls what one Lordstown worker named Ed York told him in an interview for his book Steeltown USA: “I had a half a million Vietnamese trying to kill me and I survived. What could management do to me?”

But pure anti-authoritarian defiance wasn’t the strike’s impetus. In the workers’ own words, their chief aim was “to be treated like American workers, human beings,” according to Cowie, “and not as pieces of profit-making machinery.”

This novel attitude toward work soon earned a catchy new name: “Lordstown syndrome,” as Business Week had called it, was the talk of the country in publications ranging from The Nation to Playboy. While Newsweek hailed the strike as “industrial Woodstock,” the Wall Street Journal editorial page—hardly a friend of labor—bemoaned the dehumanization of Lordstown workers in an editorial titled “The Soul Must Panic.”

GM execs were panicking too, no doubt. By mid-March, the lost output, including 50,000 unsold Vegas, had already cost an estimated $150 million (around $916 million today), according to the New York Times. With Vega production hanging in the balance, GMAD was forced to concede more than could usually be expected under the reign of Godfrey. Many of the workers laid off in 1971 were given their jobs back. Those suspended for disciplinary reasons were rehired with back pay. In essence, the factory reverted to pre-GMAD conditions—though the assembly lines maintained their top speed of 100 cars per hour, according to reports from Bryner in Working and coverage of the factory by The New York Times. Sufficiently satisfied with the terms, Lordstown workers voted on March 26 to end the strike. The next morning, 22 days after the strike began, they were back making Vegas.

While the strike had ended, the nation’s business and political leaders continued to chew over the eponymous syndrome and the deeper malaise the strike had exposed. Those grievances sparked an intense moment of cultural introspection, including Senate hearings and an abortive effort by Ted Kennedy, the Massachusetts senator, to pass the “Worker Alienation Research and Technical Assistance Act of 1972.”

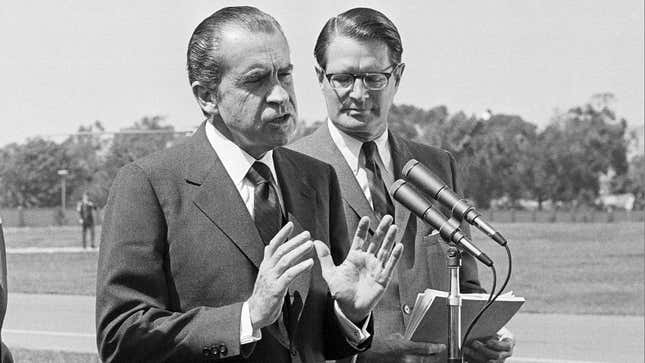

Most remarkable of all, though, was the work of a massive special task force commissioned by Elliot Richardson, a longtime public servant who was then serving as president Richard Nixon’s secretary of health, education, and welfare. The product of this effort, a report titled Work in America, offered lessons that could have changed the workplace—and possibly, American society—for the better.

The fight over productivity

Published at the end of 1972, the mammoth report probed the quality of working life and its impact on American society. In its grim and unflinching findings, GM’s Lordstown factory was exhibit A.

The report began with the bold assertion that work was an essential source not merely of self-esteem and self-worth, but of humanity. When work becomes rote and highly standardized, the report continued, workers are left with nothing to distinguish their labor from that of animals. The worst example of “dissatisfying work” came from the auto industry, “the assembly line, its quintessential embodiment.”

The issue lay with the “scientific management” principles pioneered by Frederick Winslow Taylor, whereby the two critical variables that determined a factory’s efficiency were its unit costs and output volume. Taylor’s strategy overcame individual skill differences by reducing craft into its most basic component tasks, making it possible to standardize the work quality of thousands of laborers. This concept had long ago helped raise factory productivity by making mass production possible. Automation simply advanced this process by letting technology take over certain tasks in the chain of activity.

“This is the attitude that was behind the construction of the General Motors auto plant in Lordstown Ohio, the newest and most ‘efficient’ auto plant in America,” wrote the report’s authors.

The 1972 Lordstown strike “highlights the role of the human element in productivity,” they said. The problem was, as technology allowed management to further fragment production into ever-simpler tasks, the work itself became so boring and abstract that it “dehumanized” workers, said the report. This “current concept of industrial efficiency conveniently but mistakenly ignores the social half of the equation.” Without the human satisfactions of craftsmanship and creativity to motivate workers, the report suggested, keeping workers on task required increasingly authoritarian measures—a strategy doomed to backfire. After all, asked the authors, “What does it gain the employer to have a ‘perfectly efficient’ assembly-line if his workers are out on strike because of the oppressive and dehumanized experience of working on the ‘perfect’ line?”

In fact, technology had failed in its promise to free humans from drudgery and wring profit from their talents, the authors said. On the contrary, the new jobs created generally required minimal expertise and therefore prevented workers from honing their skills. That stymied career mobility and left people mired in the same torpor of boredom for decades. Despite this, America continued to offer its young people increasingly rigorous education—even as work life left little opportunity to apply it.

These dynamics were exacerbated by the economy’s changing structure. Huge corporations and bureaucracies that had emerged in the previous decades organized work so that it maximized top-down, central control and stifled worker independence. And though Lordstown’s unrest put “blue-collar blues” front and center, the rise of computers were creating similar “white-collar woes” too, the authors argued.

“With the shift from manufacturing to services,” they wrote, “the tyranny of the machine is perhaps being replaced by the tyranny of the bureaucracy.”

Corporations hadn’t adapted to their outsize impact on American society, though. Under the status quo, corporations were free to ignore the social costs they incurred, including “job-related pathologies” like alcoholism, drug addiction, mental and physical illness, violence, welfare dependency, and political alienation.

The report’s extensive recommendations could be distilled into a simple two-part reform. If America was to treat the underlying cause of Lordstown syndrome, and not just its symptoms, US companies had to manage workers in a way that encouraged their participation, and allowed them to share in short-term profits. These changes, the report said, would help lead to “healthier and more productive workers and citizens.” While undertaking these changes would fall to firms and labor unions, government had a role as a catalyst for reforms, the authors noted, citing the Swedish government’s initiative in helping companies like Saab and Volvo change their assembly line operations.

Might this analysis have prompted the government to spearhead the cultural shift its authors advocated? We’ll never know. Whatever momentum the report might have had was soon overwhelmed by political scandal. In 1973, Richardson was appointed Attorney General. Mere months later, in what became known as the infamous Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon ordered him to fire the special prosecutor investigating the Watergate scandal. In a move that stunned the nation, Richardson resigned. Less than a year later, Nixon stepped down too.

The larger hopes and ambitions of Work in America—the vision that saw satisfying work itself as essential to the health of American society and democracy—exists now as little but a curio in the footnotes of academic journals. The free-market ideology that became Republican party doctrine in the late 1970s (and by the 1990s heavily influenced the Democrats as well) rejected altogether the report’s holistic notion that people and their work are community resources—and, consequently, that choices of how to value and allocate those resources should ultimately be up to society, as well as businesses.

GM treats the syndrome

In the end, GM did eventually back away from its authoritarian management style. It began involving workers more actively in the production process and increased attention to ergonomics improved the physical strain of working conditions. Though these reforms took place throughout the 1970s, they were largely in response to the Lordstown strike, says Youngstown State’s Russo.

For most assemblers, though, the tedium and inflexibility continued. Kenneth Picklesimer, the former Lordstown worker, wound up putting springs on axles for 17 years. “I would have preferred to mix it up but I didn’t have opportunity or choice because…there were too many people with more seniority able to bid on and get other jobs.”

Meanwhile, GM continued to lavish spending on big capital investments, confident that the secret to competitiveness lay in replacing humans with technology. But as in Lordstown, the spending bore little fruit. As automotive analyst Maryann Keller recounted in her 1989 book Rude Awakening, one GM executive observed that, between 1980 and 1985, the company shelled out an eye-popping $45 billion in capital investment. Despite that spending, its global market share rose by but a single percentage point, to 22%. “For the same amount of money, we could buy Toyota and Nissan outright,” said the executive—which would have instantly bumped GM’s market share to 40%.

One casualty of the showdown in Lordstown was the Vega. After a solid debut, sales peaked in 1974; in 1977, GM retired the car altogether. Though the strike undoubtedly sullied the Vega’s reputation, GM’s quality problems proved to be much deeper and more enduring. By the mid-1980s, the flaws in design and engineering epitomized by the Vega had congealed into reputation.

“General Motors is the object of suburban dinner-table scorn,” wrote Harvard management guru Rosabeth Moss Kanter in her influential 1984 book, Change Masters. “Cars are a common topic of conversation, and everyone I meet seems to have an anecdote explaining why American car manufacturers are losing ground to the Japanese. In all these stories, cost is not the issue so much as a perception of quality difference.”

Plus, the US auto market dynamics changed profoundly in the intervening years. After two oil price shocks rocked America in the mid-1970s and early 1980s, leading to a permanent increase in gas prices, GM’s albatross—its inability to make a small, fuel-efficient car for the masses—became a real vulnerability.

By the late 1970s, Japanese carmakers had triumphed decisively in the battle for the subcompact market—and they’d won it on performance, reliability, and cost. How? Automobile quality, it turned out, wasn’t strictly a function of the fanciness of a factory’s machines. In fact, the Japanese formula for success could have come straight out of Work in America: Trust that people want to do good work, and treat them accordingly.

In workers they trust

When Honda set up the first Japanese-brand US auto plant, in Marysville, Ohio, in 1978, it brought with it starkly different values from those that prevailed in Lordstown.

At GM—and at Chrysler and Ford—factory life was organized by stark, ubiquitous hierarchies. Managers enjoyed heated parking garages, where their cars were washed and tanks filled with free gasoline each day. They wore ties and ate lunch in posh executive dining rooms.

Not at the new Honda plant. Parking was on a strictly first-come, first-served basis. Managers wore the same uniforms as assemblers and changed clothes in the same locker room. As Ingrassia recounts in Crash Course, Honda insisted that its assemblers be called “associates,” not just “workers.” The point, explained Shige Yoshida, the man leading Honda’s effort, was to get both managers and “associates” to see themselves as having a shared sense of purpose.

It wasn’t just Honda. When Nissan launched its first US beachhead, in Smyrna, Tennessee, in 1983, it hired a Ford veteran named Marvin Runyon, as trade expert Clyde Prestowitz recounts in his 1988 book Trading Places. Runyon wore the same blue jumpsuit as assemblers and ate lunch alongside them in the company cafeteria. Erasing the symbolic gap between the assembly line and the executive office was key to building the worker’s sense of identification with the company, he said.

Of all the Japanese carmakers, Toyota is the most famous for translating culture into consistently high productivity and quality. Toyota’s success lay in the trust its management invested in its workers to catch and correct defects. The company grouped its assembly line into “quality circles,” small teams that were responsible for quality control. These teams were tasked with looking out for flaws as the cars went down the line. When a worker spotted a defect, he had a range of choices for fixing it. Of these, the most extreme options—and symbolically important—was the Andon cord, a sort of emergency brake that would, once pulled, immediately stop the assembly line.

Economist Paul Collier offers some useful financial context for the significance of this responsibility. “By its nature, assembly line production is so integrated that stopping the line is spectacularly costly. In the Toyota factory, it cost $10,000 per minute,” explains the Oxford professor in his new book, The Future of Capitalism. In other words, yanking on the cord unnecessarily would cost the company in the course of a few seconds more than the worker himself might earn in the entire month. That power, says Collier, “indicated that the management really trusted their workers to work for the company, not against it.”

The Andon cord example hits on something deeper than just management strategy. Rather, it plumbs a core difference between Toyota’s and GM’s underlying assumptions about what motivates people to work.

“American companies tend, fundamentally, to mistrust workers,” writes Keller in Rude Awakening. “There is a pervading attitude that ‘if you give them an inch, they’ll take a mile’ because they don’t really want to work. The idea, for example, that a worker in the plant would have the power to stop the line in order to eliminate a problem was heresy. Wouldn’t such permission lead to widespread line-stoppage for every whim?”

Not, obviously, at Toyota plants. The operating assumption was that everyone was there to do good work. Management’s job was to help assemblers have the resources they needed to do that. The company had neither a concept of “quality control” nor inspectors charged with enforcing it. That everyone held their work to the highest standards went without saying. Ensuring flawlessness wasn’t a final step in the production process; it was expected throughout.

By contrast, GM’s mistrust of its workers ultimately prevented it from making great cars, argues Keller. That was why the company turned assembly work into an interlocking chain of discrete tasks, to be executed by robots whenever possible. Responsibilities were narrowly defined. Workers were to perform their specific task, again and again. Managers made sure they did that. But no one was focused on the product as a whole. In this highly fragmented process, “quality” wasn’t a shared standard; it was a step in the process that came at the end, when the “quality control” inspectors (or, under Godfrey’s watch, computers) checked already-finished cars. By that point, it was already too late to be exacting.

Instead of making flawless cars, workers simply did their assigned jobs. Workers had no big-picture goal of building cars together to motivate them. They had no control over the effectiveness of the process or the quality of parts they used. So management relied on threats and intimidation to keep them moving—in the process, deepening the us-versus-them divide.

GM missed the chance to learn these lessons from the Lordstown strike. As luck would have it, another chance came along a decade later—at GM’s own initiative.

In 1983, GM made the bold move of teaming up with Toyota to build small cars in a plant near Oakland, California—a venture better known as NUMMI (New United Motor Manufacturing Inc). The goal was for GM managers to master the secrets of Japanese competitiveness. GM bosses had expected to find that Toyota’s manufacturing prowess came down to its automation, says Keller. What the 16 American employees GM execs dispatched to NUMMI to work learned instead was that Toyota’s superior quality and efficiency was largely thanks to how it trained and valued its workers. The results were impressive.

“At the time, GM had a scoring system in which 145 was perfect. Most GM factories would celebrate if they hit 120,” Ingrassia writes in Comeback. “Nummi quickly began turning out cars that averaged 15 or more points higher. Eventually, Nummi even had some cars hit a perfect 145.”

But nothing came of it. “Instead of coming back to the 16 of us and saying, ‘There’s some secret sauce here, what is it? How can we use it to our advantage?’ No one ever asked us that question,” Steve Bera, one of the 16 employees, told NPR in 2010. Bera quit in frustration, ending his 20-year career at GM—and taking his NUMMI-gleaned expertise with him.

Nearly three decades after the Lordstown strike, GM’s quality still suffered from the deep distrust between labor and management. “The factories tend to have the least flexible work rules of the Big Three auto makers, forbidding assembly line workers, for example, to perform other tasks when the line stops,” the New York Times’ Keith Bradsher reported in 1998. “Workers fear there would be unreasonable demands from foremen if the work rules did not exist.” By comparison, Ford and Chyrsler prioritized labor relations and, more generally, treated their workers better, according to Bradsher.

Its failure to compete in the small car market helped push GM—and the rest of Detroit—toward embracing the higher-margin big car market. This strategy has proven profitable, but also risky. The steady rise in oil prices throughout the 2000s, peaking in July 2008, was one of several factors that pushed GM into US government-led bankruptcy in the midst of the financial crisis. Perhaps fittingly, that year, Toyota finally ousted GM as the world’s biggest producer of vehicles—a status GM had claimed for 77 years.

Rebirth?

Even bankruptcy didn’t stymie GM’s small-car ambitions. In 2010, as it had in 1968, GM was throwing down the gauntlet once again. And, once again, the hype was intense. The Chevy Cruze was its first major new model to debut since Chapter 11.

And, naturally, Lordstown was going to be making it. “The rebirth of the American economy starts right here at Lordstown with a world-class, high-volume car built in the heartland of America,” Mark Reuss, president of GM’s North America operations, told the New York Times (paywall) at the time of the launch. “This is our first demonstration that we’re going to win in this marketplace.”

It was a sound choice. A top seller abroad, the Cruze boasted 40 miles per gallon, compared to around 36 for the Honda Civic. But in the years since the car’s promising American debut, low gas prices have revived Americans’ on-again-off-again love affair with trucks and SUVs, dealing a brutal blow to car sales. Last year, Americans bought around 4.6 million passenger cars, around 18% fewer than in 2014.

Under Mary Barra, a former engineer who took over as CEO in 2014, GM is now prioritizing high-quality autos and safety standards, sales volume and market share be damned. But old habits die hard. Along with the rest of Detroit, GM dominates America’s big vehicle market, allowing it to command a much bigger premium than the margins it can earn on small cars. Coupled with the slumping small-car sales, that’s why GM’s announcement in November 2018 that it would end production of the Cruze and most of its other sedans was not particularly surprising. Indeed, GM’s not alone: Ford announced the end of new sedan production for the US market last spring, and Fiat Chrysler threw in the towel on US passenger car production in 2016.

End of the line

Among the many reasons Work in America is such a fascinating document is the disturbing accuracy of its prophecies of social decay. In this, Lordstown is once again a handy Exhibit A. Unemployment in the Youngstown area that surrounds Lordstown is higher than any other city in the state of Ohio. As steel mill closures that began in the late 1970s drove deindustrialization, crime in Youngstown rose; the city became notorious for its organized crime and corruption. The opioid crisis has hit Youngstown particularly hard.

As for the fate of the Lordstown factory, there’s still a chance GM might upgrade the facility to make one of its new models, as Youngstown residents we spoke with were quick to emphasize. (GM did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.) Or it’s possible that Lordstown Assembly will remain standing, but empty, a vast roadside reminder of a corporate elite’s doomed quest to cheapen labor by stripping the human need for skill, learning, independence, and purpose out of production, by reimagining people as machines.

To Tim O’Hara, GM’s recent Lordstown decision is bitterly ironic given that the plant is now—finally—“building the best quality car that we’ve probably ever built in the last 52 years.” He’s talking about the Cruze. Last year, Consumer Reports judged it the best compact car on the market, a title usually dominated by Toyota and Honda subcompacts. After a half-century of trying, Lordstown had finally broken the curse of the Vega.

Or had it? Last year, GM sold nearly a third fewer Cruzes than it did in 2014. It could be that GM has simply grown too dependent on marketing to red-state consumers who vastly prefer its trucks, at the expense of reaching small-car consumers. But Kenneth Picklesimer still looks back to the early 1970s for the original sin of GM’s small-car quality. “I think the perception goes back to the Vega,” he says.

Picklesimer retired in 2015. The timing was good: his last 12 years at Lordstown were his best. At last liberated from spring-bolting, he was assigned to a new job coordinating with engineers to design parts and plan production for the Cruze and its predecessors.

It was a long-desired break from decades of repetition. But the work meant more to Picklesimer than that. “I loved it. It gave me the chance to learn, to teach other people. I was able to make changes and give input on…the Cruze, to make them better cars that are easier to assemble,” he says. “We could make a difference that way.”