Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe has a near impossible feat to accomplish in the new year—convince Vladimir Putin to give up Russian territory.

The land in question is a chain of tiny islands known as the Southern Kurils to Russia and the Northern Territories to Japan, and the dispute over them has dogged relations between the Pacific neighbors since the end of World War II. In recent weeks, the two countries have signaled renewed efforts to bring the disagreement to an end.

The two leaders met in Singapore in November and agreed to move forward with negotiations to return the islands of Shikotan and Habomai to Japan, based on a 1956 joint declaration signed by the then Soviet Union. Further progress on that stalled after Japan also demanded the return of two other islands that make up the majority of the territory in dispute.

Abe’s recent posture, however, suggests that he is willing to accept the return of just two of the islands in return for a peace treaty with Russia. The leaders could meet in late January in Russia, the Kremlin said this month.

The four islands are the southernmost of a chain stretching between the two nations, and were signed to Japan by Russia in 1855, but the Soviet Union seized them at the end of World War II. Today, Japanese are able to visit the islands under a visa-free arrangement between the two countries, with visitors including (paywall) those who want to pay respects to their ancestors buried there, or to visit the hometowns of their relatives.

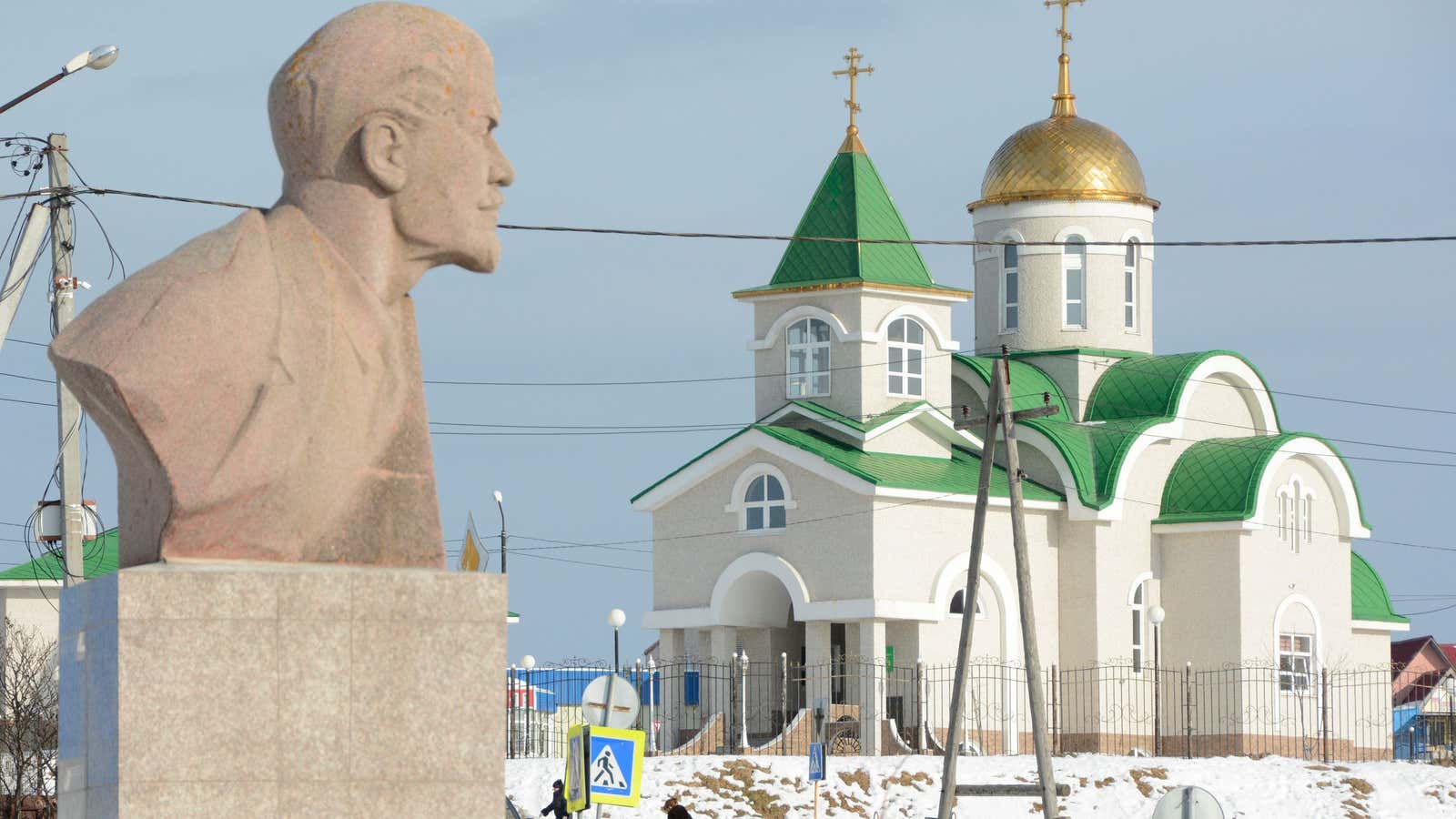

The compromise of settling for the return of just two of the islands is gaining acceptance in Japan, with 46% of people (paywall) in a survey conducted in November supporting such a move. In Russia, however, handing over the islands—where thousands of Russians are currently living—is extremely unpopular (paywall) among the public.

For Abe and Putin, settling such a long-running territorial dispute would be a boost to their legacies, but a peace treaty could also viewed as a way counterbalancing China’s (paywall) growing influence in the region.

But it seems that a resolution is more beneficial to Japan than to Russia. As Dmitri V. Streltsov, a Japanese studies expert at the Russian Academy of Science recently argued (paywall), in addition to a lack of public support for returning any of the islands to Japan, most Russians simply don’t see Japan as a strategic priority for Russia, particularly at a time when relations with the US—which also happens to be Japan’s closest ally and security guarantor—are in such a tense state.

Japan’s relationship with the US has, in fact, long colored Russia’s intransigence toward the disputed islands. Moscow fears that if the islands are returned to Japan, the US could build military bases there, and the Kremlin already sees Japan’s recent decision to deploy a US-made missile-defense system as a military threat. Putin has pooh-poohed the idea that Japan has any control over the location of US bases by drawing attention at his annual year-end press conference to the construction of a new American facility (paywall) in Okinawa that has gone ahead despite strong local opposition.

Russia has continued its military fortification of the islands, and earlier this month said it would build new barracks for troops on Iturup (Etorofu) and Kunashir (Kunashiri). Japan has lodged an official protest against the move. Japanese media also reported today (Dec. 31) that, according to a government document drafted a few months ago, Russia is planning to increase its missile-defense capabilities in the waters near Hokkaido by 2020.