How does a museum go about borrowing $4.4 million in gold?

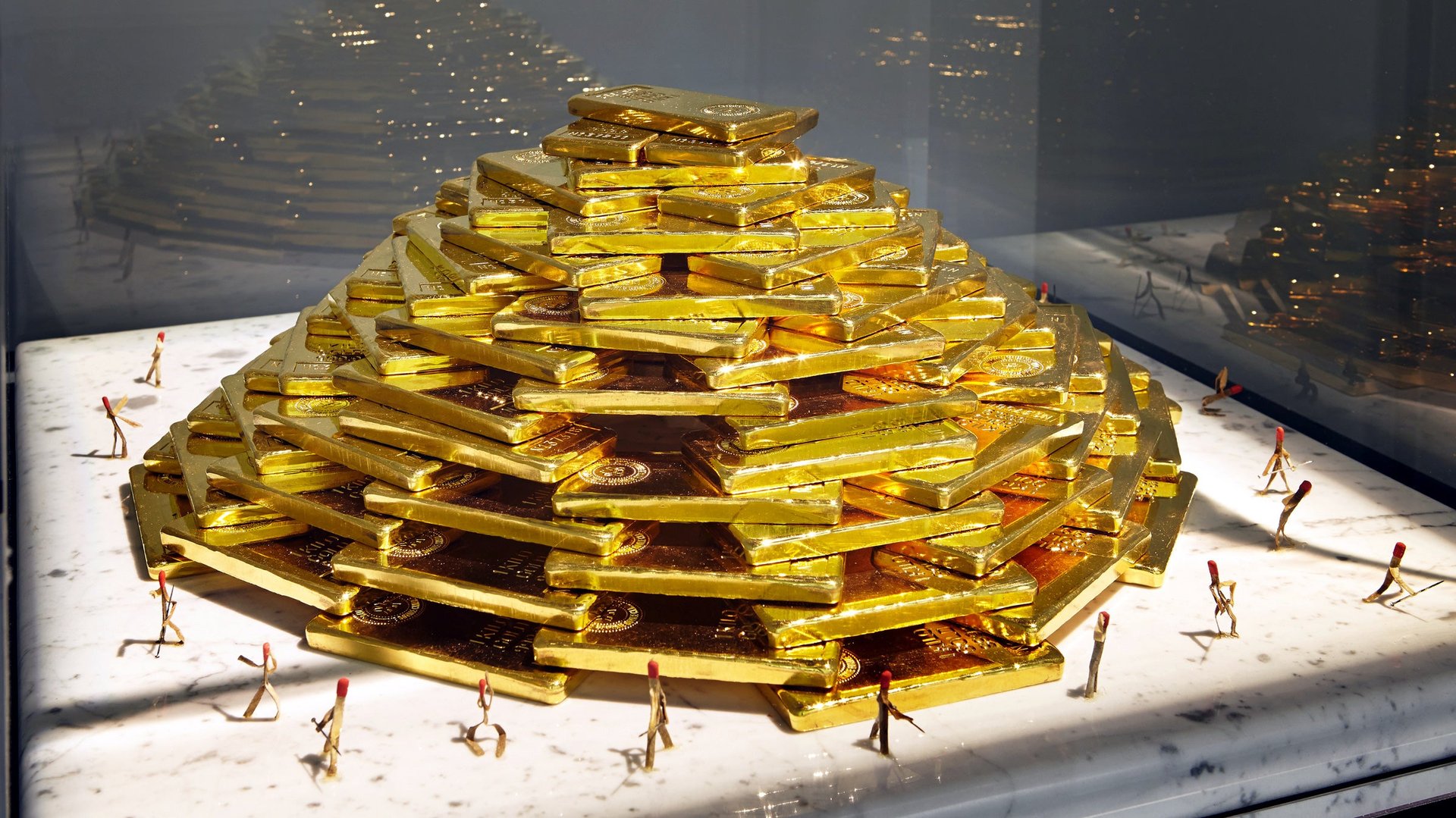

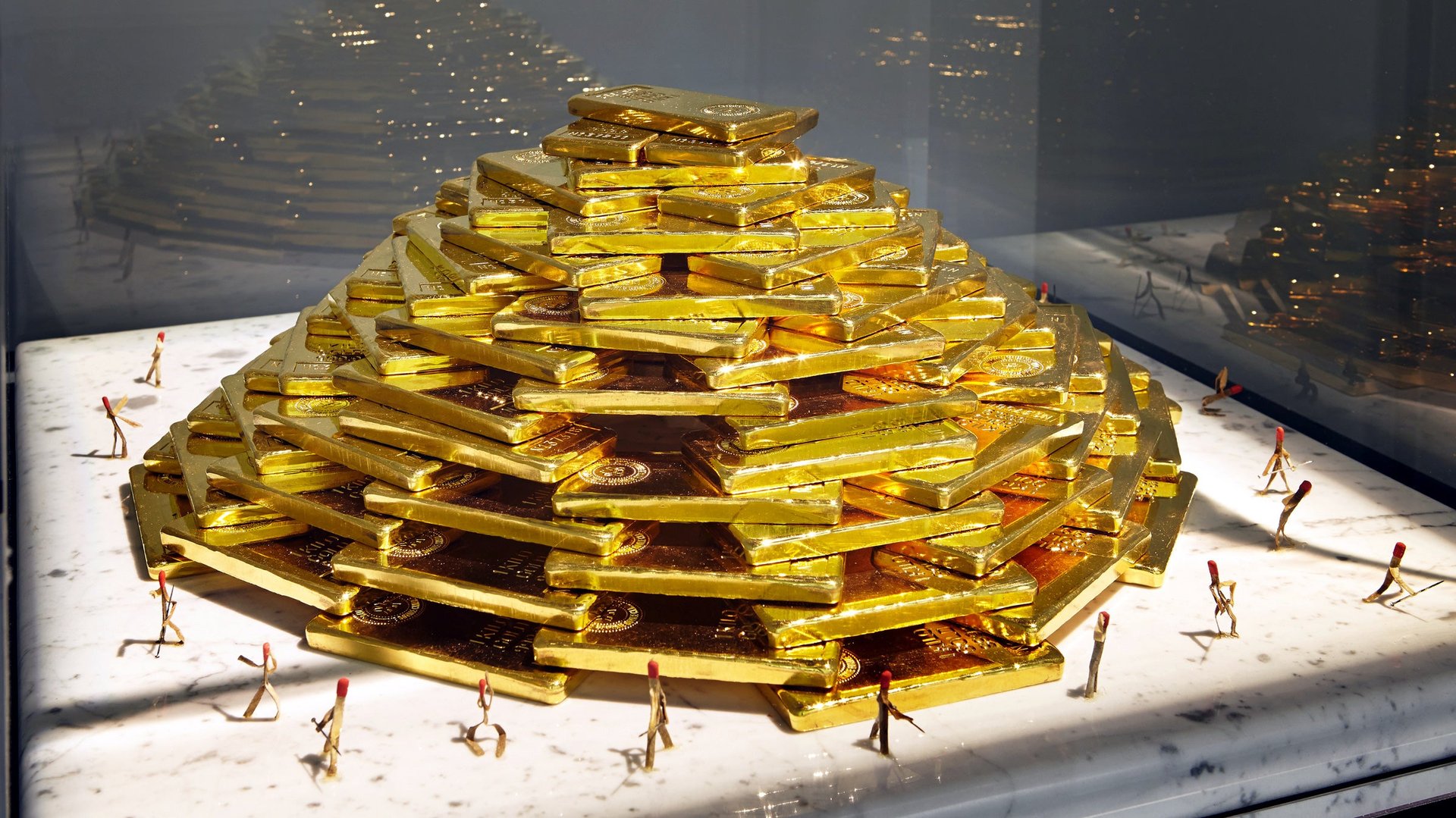

Tower of Power is a sculpture built out of one hundred one-kilo (thirty-two ounce) bars of pure gold. On the marble surrounding of the tower are several paper matchstick men in various forms of tribute. Like the matchstick men, our lives are relatively transient and consumable in relation to the ascribed and lasting power of gold.

Tower of Power is a sculpture built out of one hundred one-kilo (thirty-two ounce) bars of pure gold. On the marble surrounding of the tower are several paper matchstick men in various forms of tribute. Like the matchstick men, our lives are relatively transient and consumable in relation to the ascribed and lasting power of gold.

—Chris Burden, 1995

The last time they tried to display this art work, it was stolen.

Not by thieves, but by the infamous Ponzi schemer Allen Stanford. The Gagosian gallery, which represents Burden, had arranged to purchase the bullion from one of Stanford’s companies in 2009, but when federal law enforcement seized his assets, they also froze the gold, leaving the piece without its primary ingredient. “We expected the guys with guns to steal it,” Burden said, “but it was the men with coat and ties.”

This year, the piece is on exhibit for the first time in the United States since 1986 (and only the second time ever!) at New York’s New Museum.

“When he first made it in the eighties, his idea was to show a million dollars worth of gold, what does that look like,” Lisa Phillips, the museum’s director, told Quartz. “Now, in relation to 100 million dollar art objects, it seems very modest.”

There’s still no gold to go with the piece, so the museum had to borrow it using funds provided by Lonti Ebers, the vice-president of the the Museum’s board of directors, and Bruce Flatt, the “Warren Buffet of Canada.” When the 2009 exhibit fell through, the gold was worth $3 million. Today, the same amount of gold is worth $3.9 million. But when the exhibit first opened last month, it was worth $4.4 million—a testimony to gold’s volatility.

Art museums are accustomed to dealing with valuable objects, but a pile of gold is unique. Half the problem of stealing art is how distinctive a masterpiece is, making fencing the goods difficult at best. But gold is gold, and so the New Museum has had to obtain a massive insurance policy and create new security procedures, including an armed guard. Museum-goers can join the guard to view the piece behind a plexiglass screen one at a time, without any bags or jackets. When the exhibit closes in January, the gold will have to be melted down, assayed and remade into bricks in order to make sure that less valuable metals weren’t switched in.

Burden is a critically acclaimed artist, perhaps most famous for his early work “Shoot,” wherein he filmed himself being shot in a Los Angeles art gallery in 1974. His work spans the gamut from performance to sculpture, and generally deals with the concept of power. While Phillips calls this piece “one of his purest expressions,” no one has purchased it.

“It really surprises me that this historical work is not owned by a museum or a private collector,” Phillips says. “It has something to do with the fact that it’s a very big responsibility to insure and maintain, and two, you have to supply the gold, and people see it as a representation of pure value but in fact it is a work of art. What is the value that one can ascribe to the idea? Ok, I supply x million dollars worth of gold, should I pay anything on top of that for the work of art? What is it worth? That’s what he’s playing with in this piece anyway, our notion of values, of financial value and worth, and how it changes over time. It changes day to day, in this case.”

In this age of bubbles and irrational markets, an artwork whose value can be precisely measured day-to-day—while remaining priceless—seems all too perfect.