For most of his life, billionaire Len Blavatnik put few of his vast resources into US politics. That changed in 2015.

Since then, the oligarch, a US citizen who was born and raised in the former Soviet Union and made his fortune in Russia, has donated more than $6 million to Republicans, according to Federal Election Commission data cited by the Dallas Morning News, plus $1 million to Donald Trump’s inaugural committee, and several hundred thousand dollars to Democrats, including relatively small sums to senators Kamala Harris and Ron Wyden, FEC filings show.

The question of Russia-linked money entering US politics has been of interest to law enforcement and congressional investigators since reports of Moscow’s meddling in the 2016 presidential election surfaced that year. Now, numerous ties between the Kremlin and people in the Trump orbit have been revealed, and Russian graduate student Maria Butina has pleaded guilty to trying to infiltrate the Republican party as a foreign agent for Russia.

Quartz’s reporting shows that, during at least part of the time Blavatnik was stepping up his GOP donations, one of his many companies was partnered with a firm that was reportedly part-owned by a then-official in the Russian government. He also was in business with two other oligarchs now sanctioned by the US government. (Blavatnik’s contributions are legal—he became a naturalized US citizen in 1984.)

Asked in September 2017 by ABC News about a report that US special counsel Robert Mueller was looking into donations to Trump’s inauguration fund by Blavatnik and other Republican donors with Russian ties, Adam Schiff, now chair of the House Intelligence Committee, said, “if there were those that had associations with the Kremlin that were contributing, that would be of keen concern.”

Federal prosecutors in Manhattan are also reportedly investigating whether big donors to Trump’s inauguration committee gave money in exchange for access to the administration. It’s unclear if they are looking into Blavatnik, but his was among the bigger donations to the controversial fund.

Blavatnik owns stakes in companies that have together received millions of dollars in contracts from sensitive US government agencies such as the departments of Defense, Energy, and Homeland Security, according to federal filings. Those firms include biotech company Humacyte, chemicals firm LyondellBasell, and natural-gas giant Calpine, which was recently bought by a consortium co-led by Blavatnik’s main holding company Access Industries.

Access Industries declined to answer detailed questions for comment on this story, sending a short statement via an outside public-relations company that said Blavatnik’s donations are “motivated by a desire to further a pro-business, pro-Israel agenda,” and “are a matter of public record and comply with all legal requirements.” Humacyte, LyondellBasell, and Calpine didn’t reply to emailed requests for comment.

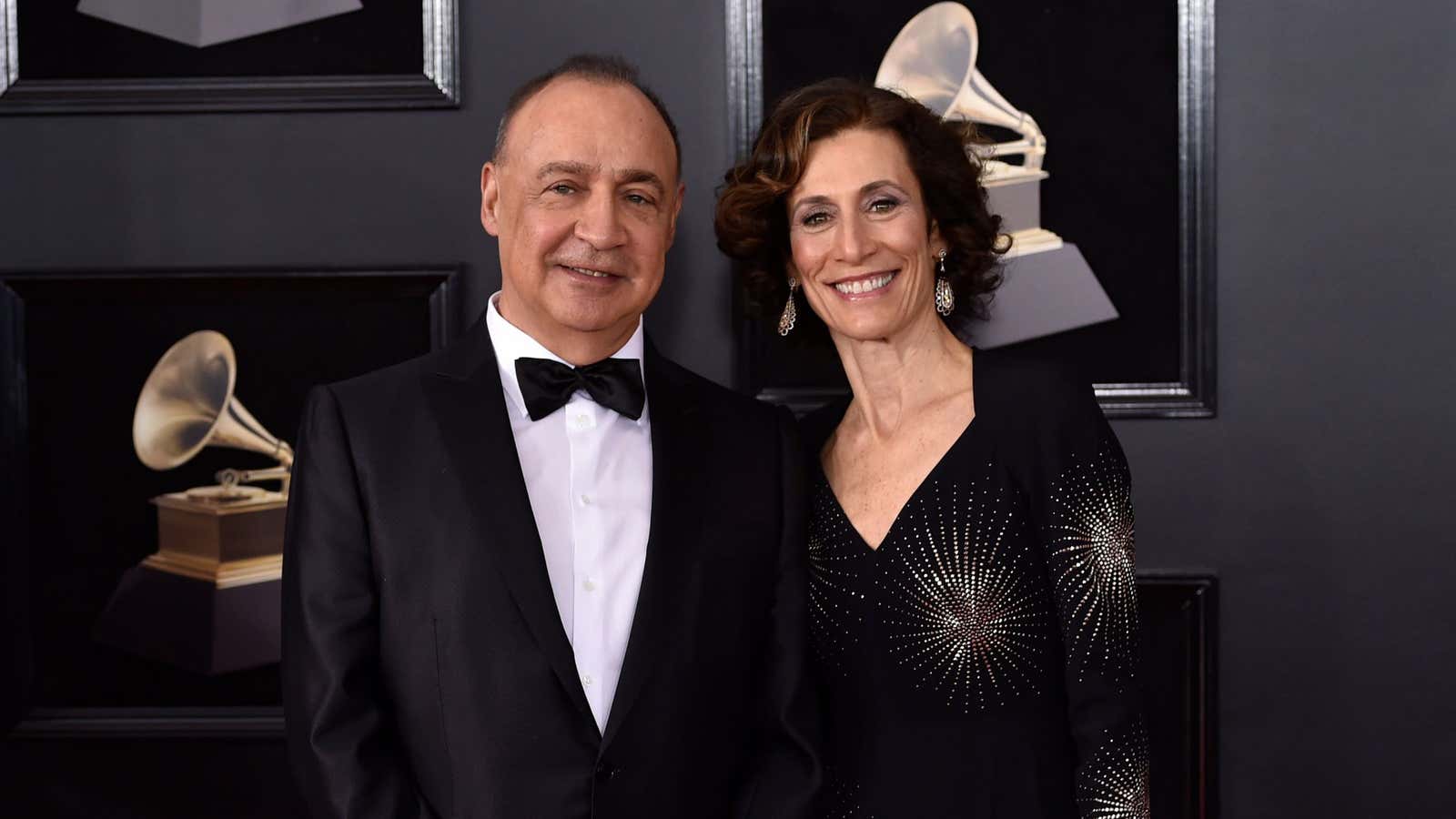

Meet Len Blavatnik

Blavatnik left the USSR for America at age 21 in 1978, became a US citizen, and returned to Russia as a businessman in the 1990s. He swiftly became one of the richest of a generation of post-Soviet oligarchs, making a fortune in the newly privatized oil sector and the notorious “aluminum wars.”

As recently as May 2016, Blavatnik’s business linked him to Russia’s then-deputy minister of Internal Affairs, Alexander Makhonov, Panama Papers files show. Amediateka, a major Russian TV-streaming company majority owned by Blavatnik’s Access Industries, seems to have outsourced part of its subscription services to Nemo TV, a company in which Makhonov and his business partner Dmitry Karyakin, who apparently founded Nemo, reportedly held a stake via offshore companies. Nemo also reportedly embedded Amediateka into its product and was its “exclusive technology partner” for smart TV platforms, according to a former Nemo executive. (The size of Makhonov’s stake in Nemo is unclear. When he and Karyakin set up what was reportedly the parent company for their offshore businesses in 2012, they split the shares 50-50. It’s unclear if the ownership structure changed or if there were other investors in Nemo.)

The connection between the two companies and Makhonov’s stake in Nemo TV was first reported by investigative journalism nonprofit OCCRP, based on Panama Papers files. That story didn’t mention Blavatnik or his umbrella company Access Industries.

It’s unclear whether Blavatnik had any interaction with Makhonov through the arrangement, but the small window into the apparent offshore entanglements of Russian businesses provided by the Panama Papers shows that Blavatnik did indeed share financial interests with a Russian official while heavily donating to the Republican party. There is no allegation of any illegality in these shared interests nor in holding those interests while making US political donations.

As number two in the Interior Ministry, Makhonov had a critical role in Russian law enforcement. His former boss Alexander Prokopchuk recently lost a bid to lead Interpol, after human-rights activists and US senators accused him of using Russia’s Interpol office to go after Kremlin enemies. Makhonov resigned from his government role—the level below a cabinet position—in October 2017, after an official he had hired was arrested in a corruption scandal. (Quartz was unable to reach Makhonov for comment on this story.)

Louise Shelley, director of George Mason University’s Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center, says these government ties are indicative of Russia’s general business climate. “To operate the businesses [Blavatnik] does, you can’t be a major actor without political ties—that’s just the way business operates [in Russia],” says Shelley, author of Dark Commerce. “It’s very hard to function in the [commodities] sector without having those relationships.”

The ties to Makhonov and other Russian oligarchs suggest Blavatnik “has good relations with people high up in the Russian government,” says University of Dallas academic Ruth May, who first unearthed many of Blavatnik’s political contributions in two Dallas Morning News pieces.

Blavatnik’s donations to US politicians

Between 2009 and 2014, Blavatnik, a dual US-UK citizen, had been giving relatively small donations to both US political parties; his biggest spend was a total $273,600 in the 2014 election cycle.

However, from 2015 to late 2017, he donated at least $6.35 million to Republican party institutions, PACs, and candidates, May wrote in the Dallas Morning News, based on FEC data. He gave the money in a mixture of personal donations and contributions via Access Industries and AI Altep Holdings, which he also reportedly owns. (The two firms share the same CEO and Blavatnik’s brother is listed as AI Altep’s director, according to Open Corporates.)

Most of that cash went to Super PACs associated with Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell and onetime presidential candidates Marco Rubio, Scott Walker, John Kasich, and Lindsey Graham. McConnell, Rubio, Walker, and Kasich didn’t respond to emailed requests for comment. A spokesman for Graham said the South Carolina senator “has been one of the harshest critics of Russia/Putin out there” and noted that it’s illegal for candidates to coordinate with Super PACs, while inexplicably linking to an article on how politicians are almost never actually punished for such coordination.

Trump’s campaign didn’t receive any Blavatnik cash during the 2016 campaign but he has donated large sums to the Republican National Committee’s legal fund, which has helped finance Trump’s legal defense for the Russia probe, according to the Wall Street Journal. He also gave $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee. The committee raised an astonishing $107 million and reportedly spent $104 million; around double the cost of Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural celebrations. More than $1.5 million went to Trump’s hotel in Washington, according to the New York Times. The White House did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Two donations had particularly bad optics, May says: $1 million to the McConnell-associated Senate Leadership Fund PAC on Oct. 25, 2016, and $250,000 to the Rubio-tied Florida First Project on Oct. 27. Two weeks earlier, America’s top intelligence officials had accused Russia of hacking Democratic National Committee servers. Former vice president Joe Biden has since accused McConnell of refusing, during the 2016 campaign, to sign onto a bipartisan statement criticizing the Russian attacks. Neither McConnell nor Rubio replied to emailed requests for comment.

In a letter sent to Quartz in December, Blavatnik’s lawyer, Martin Singer, denied any suggestion of wrongdoing by Blavatnik, saying that he had “zero” involvement in Russian politics.

Blavatnik also gave hundreds of thousands to Democrats in the same period. Senators Harris, Wyden, and Bob Menendez were among the dozen or so politicians to receive comparatively small donations. None of the three senators have replied to emailed requests for comment.

Blavatnik’s donations to right-wing causes continued late into 2018. His foundation paid $50,000 to be the “Patron Sponsor” of the conservative Hudson Institute think tank’s annual gala on Dec. 3, honoring the outgoing House speaker Paul Ryan and UN ambassador Nikki Haley. Past Hudson Institute honorees include former president Ronald Reagan, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger, and vice president Mike Pence. The founder of Hudson’s vaunted Kleptocracy Initiative, which publishes reports on the influence of Russian money in global politics, quit the think tank as a result of the donation, telling the New York Post: “Blavatnik is precisely what the Kleptocracy Initiative is fighting against.” The Hudson Institute did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Since becoming a British citizen in 2010, Blavatnik has given the ruling Conservative party £94,500 ($121,000), according to Britain’s Electoral Commission. The Conservative party did not respond to a request for comment.

Blavatnik the philanthropist

Blavatnik takes great pains to distance himself from Russian politics. Within hours of describing Blavatnik as an “oligarch” when breaking the news of his donation to Trump’s inaugural committee in 2017, Quartz received an email from his PR representative. An outside spokesperson for Blavatnik’s Access Industries called the term oligarch “both highly inaccurate and offensive,” arguing that it implied having a “great deal of political influence” in Russia. The spokesperson said that Blavatnik hadn’t had any contact with president Vladimir Putin since 2000 and that he “plays no role in Russian politics.”

The tycoon has instead styled himself as a “major American industrialist and philanthropist.” In 2017, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth for services to philanthropy. Candidates for knighthoods are typically recommended by the British government, currently headed by Conservative prime minister Theresa May.

He is a major funder of institutes, government schools, museum wings, and even seating tiers at the likes of Harvard, Oxford, London’s Tate Modern, and New York’s Carnegie Hall. A Tate spokesperson said Blavatnik has “a well-known track record for philanthropy” and that the museum is “grateful for his generous support.” The other three institutions didn’t reply to emailed requests for comment.

Under Mueller’s eye

In September 2017, an unnamed Republican campaign aide who had been interviewed by Mueller’s investigators told ABC News the probe was looking at the timing of contributions to Trump’s political funds by Blavatnik and two other US businessmen with Russian ties.

Mueller has taken an interest in Blavatnik’s longtime business partner Viktor Vekselberg, who reportedly met with Trump’s then-personal lawyer Michael Cohen just days before Trump’s inauguration. A couple of weeks after that meeting, a private-equity firm run by Andrew Intrater, Vekselberg’s cousin, paid Cohen $1 million in consulting fees. (Intrater says Vekselberg had nothing to do with the decision to pay Cohen.)

Earlier this year, Mueller‘s team questioned Vekselberg, according to the New York Times and CNN. Vekselberg has since been sanctioned by the US Treasury in response to a broad array of alleged global “malign activity” by the Kremlin. Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin said the sanctions targeted oligarchs who “profit from [Russia’s] corrupt system.” Vekselberg reportedly had $1.5 billion to $2 billion of his firms’ assets frozen due to the sanctions. The Treasury department added that two of Vekselberg’s top executives were arrested in 2016 for bribing Russian officials.

As recently as April, Blavatnik and Vekselberg’s company Sual Partners owned 26.5% of Rusal, an aluminum giant long owned by yet another Russian of interest to Mueller: Oleg Deripaska.

A close Putin confidante, Deripaska’s relationship with former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort is one of the central questions of the Trump-Russia affair. In the wake of Russia’s attack on the 2016 election, Deripaska and Rusal were sanctioned by the US Treasury department, which says the oligarch “does not separate himself from the Russian state” and accuses Deripaska of links to organized crime, ordering the murder of a businessman, and wiretapping a government official.

In December 2018, the Treasury department announced it planned to remove sanctions from Rusal, after the company committed to reducing Deripaska’s stake in it to below 50%. The move looks likely to go ahead despite bipartisan opposition in the House and Senate.